Dr. David E. Roffey is a 1967 DVM graduate of the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine and the founder of several companies, including Roffey Cattle Company. He recently established the Lyle E. and Alice J. Roffey, David E. Roffey DVM Scholarship Fund.

The calves just wouldn’t respond.

The year was 1968, and Dr. Roffey was one year out of vet school. They had tried the usual drugs for scours without success. So they resorted to IVs to at least keep the calves hydrated.

The problem was that no one really understood the root of the sickness. All they knew was the calves were dehydrating to death because of watery diarrhea.

The gentleman tasked with figuring it out was Dr. David E. Roffey, a resident veterinarian and assistant manager at Lamkinland, the dairy farm built by businessman Robert B. Lamkin.

During his third year of vet school, Lamkin had offered him a job after graduation, but Dr. Roffey, who often worked three jobs at once, had to decline.

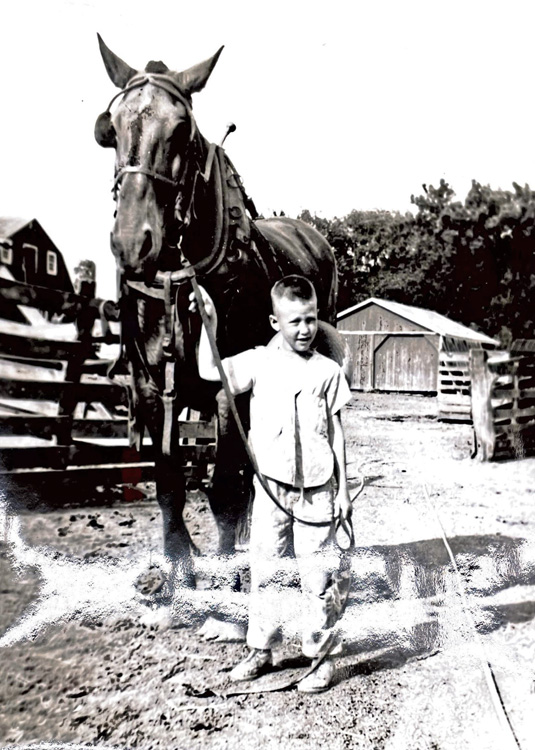

As child, Dr. David Roffey (left foreground) was fascinated when farm animals, such as this bull, needed care.

A year later, they’d brought him in, and everyone from the managers to Lamkin was expecting a rapid solution.

“What’s going on, Roffey?” they asked. “You ought to be able to figure this out.”

The pressure was on, but still no answers.

Now, his mother was involved in his career and was a great cheerleader. She happened to be reading an issue of Prairie Farmer when she came across some interesting news.

“They found a new calf organism that was killing them in Kansas and Nebraska. And so Mom had sent me that little bit of an article – it wasn’t even an article – more like a bulletin.”

He then hurried to contact the authors, Drs. Mebus and Twiehaus, from the University of Nebraska. They asked him to send samples, which he did.

They immediately discovered the same organism they had found in those Kansas and Nebraska beef herds. So they said they wanted to visit Lamkinland and arrived within a week.

“We were the first place east of the Mississippi that had discovered this,” recalled Dr. Roffey. “And once they got there and saw how we handled the cows, they used us in the experiment, trying to come up with a vaccine.”

Dr. Roffey would stay at Lamkinland for two and a half years. They didn’t develop the vaccine during that time, but they did discover rotavirus and coronavirus as the cause. “Although we did not have the vaccine at that time, we were able to save most of the calves with extensive fluid therapy,” said Dr. Roffey.

“It was just amazing. Thanks to my mother, at least we found out what it was. And so that was a tremendous boost.”

What are the odds that she would be reading that issue! As you said, it gave you a tremendous boost. So what happened next?

Well, I wanted to get on my own to make more money. I could see that I was limited. You know, I couldn’t buy part of Lamkin’s dairy, and I just needed to get out on my own. So I went to upstate New York and was brought into a dairy practice – a single man practice – that I later acquired and developed into a two-man operation.

I started doing embryo transfers early on, which was in the early seventies. At the time, there were very few—probably around five of us in the country—doing surgical ETs, or any kind of ETs. Back then, in the early stages of embryo transfer, donors were administered gas anesthesia, requiring a staff of five people. Embryos were surgically transplanted into recipients.

How did you seize that opportunity so early?

I hired a Peruvian veterinarian, and he took some of the pressure off from me. And then I also hired an Illinois graduate, Dr. Finnegan. Those two could handle the regular work of the practice, allowing me to concentrate on embryo transfer work. I had a lot of success with different cattle, mostly Holsteins and some beef animals. Then I had several production sales to sell these embryos or calves that came from the ETs from my own cattle.

You also got involved in selenium mineral.

We did a lot of infertility work and there were good herds around that area. By then I had bought a farm and had my own cattle. I was fairly accomplished at pregnancy exams. At 30 days, I could usually palpate them to do it, even sometimes at 28 days. But so often you would pronounce these pregnant, and a couple of herds would really challenge you and make you check them often.

One of the worst things a veterinarian can hear is, “Doc, you told me this cow was pregnant a couple of weeks ago and now she’s in heat. What’s going on?”

I had one particular client whose wife was rather outspoken and said, “Roffey, if you don’t figure out what’s wrong with these cattle, I’m going to fire you.” She kicked me in gear and I focused on it more. I was really determined to figure it out. I needed to identify the cause for my clients and myself, as this was happening in my own herd as well. It was found most often in well-managed herds with a diet of high moisture corn, soybean meal, and early cut legumes.

So I called Cornell and talked to Dr. Liens, who said, “Ohio State is looking at this problem with retained placentas and they’re thinking it has to do with the selenium.”

I took blood samples and sent them to Cornell, and most were very low in selenium. It took a while, but after about a year we figured out you had to give them selenium shots every week or 10 days. Subsequently I developed a feed additive with supplemental selenium.

What drove you to accomplish so much?

My motivation was I wanted a really nice farm, and I liked it. I also love the psychology of dealing with clients. I love interacting with them.

I had wonderful role models in my parents.

My father ran the dairy and addressed challenges head-on. I gained a lot at an early age watching and learning from my father as he used techniques he learned at the Graham Breeding School in 1940. This was likely the beginning of my interest in veterinary medicine. He was 75 when he died.

Mom lived to be 99 and she was in good health right up to the end. Now, my Dad had several strokes. When I was in college, he had several bad strokes. Well, the last five years of his life, he was bedridden. My mother took care of him with the help of a neighbor lady and would not let him go to a nursing home.

She had so much grit and after Dad passed away, she went on to buy more farmland and took care of her bachelor brother. She just was a wonderful example of grit and hard work.

You recently established a scholarship named after your parents, the “Lyle E. and Alice J. Roffey, David E. Roffey DVM Scholarship Fund.” What inspired you to create it?

Scholastically I was an average student. But I had motivation and determination and was not afraid of hard work. That leads to one of the factors: I want to help a hard worker who may be better at veterinary medicine than his grades indicate, one with a keen interest in the clinical side.

Secondly, farming is a tough life. It is said that farmers live poor and die wealthy. They need a veterinarian they can rely on for the present and in the long haul.

And last, I am appalled at the cost of advanced education today. I want to support that student who shows the potential to be an excellent large animal veterinarian for an extended period of time. One who will provide the medical expertise needed by his clients.

So I would like to encourage vet students to go into large animals, particularly dairy. You can make a wonderful living if you’ve got a good work ethic and if you’re ambitious. The life of a large animal vet is challenging and exhilarating. It offers the opportunities for satisfaction that you have kept animals healthy, productive and profitable.

To learn more about awards and scholarships, please email advancement@vetmed.illinois.edu.

In the recent photo at the top of the post, Dr. Roffey poses with his wife, Maggie Murphy, near a mountain lake.