Lots of kinds of parasites plague our horses, producing lots of problems. A short list of these problems includes weight loss, diarrhea, colic, unthrifty coat, skin sores, suboptimal performance, and the dreaded itchy bum.

Keep reading for details on the life cycle and signs of the critters that most commonly afflict horses in Illinois.

The Bugs

Large Strongyles

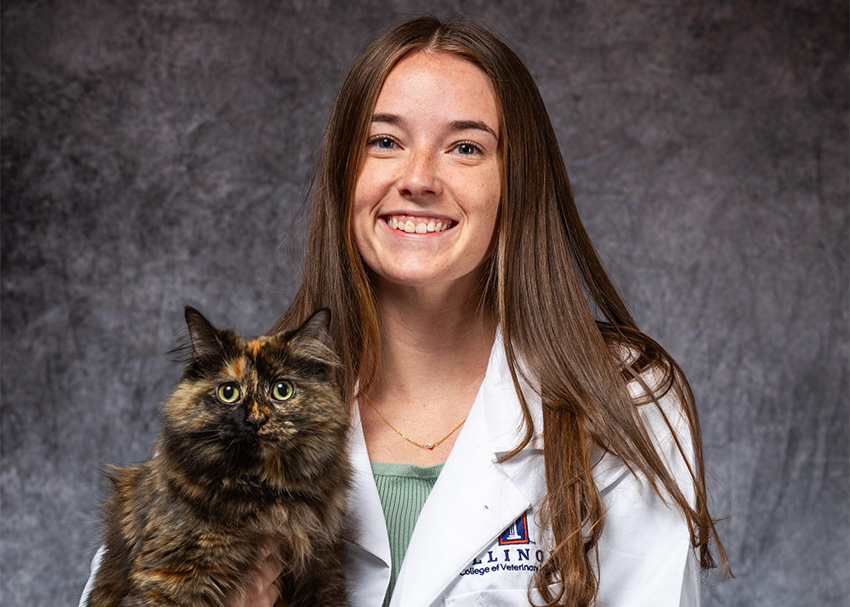

![[Dr. Kristen Stowell with her dog Oli]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/sb-horse-stowell.jpg)

Small Strongyles

These worms are much more common. The symptoms can be similar to that of large strongyles, but the way these worms cause symptoms and where they live within the gastrointestinal system is different. The larvae, or immature stage of small strongyles, encyst in the lining of your horse’s small intestine over winter after your horse has grazed contaminated pasture. The following spring, these encysted larvae, come out of their winter homes within your horse’s gut lining in a mass exodus. This can cause significant damage to the intestines.

Ascarids

Ascarids live in the small intestine of the gut. They are common in foals and can be particularly dangerous. Worms are acquired from grazing. The worms can penetrate through the gut wall and migrate to the liver and/or lungs. They are then coughed up and swallowed, where they then develop into adults within the gastrointestinal system. Because these worms can migrate to the lungs, infected horses may show signs of respiratory disease such as cough or nasal discharge.

Bot Flies

During the summer months, bot flies lay small yellow eggs on your horse’s legs and coat. Horses ingest these eggs when they itch or groom each other. The eggs molt to the larval stage within your horse’s mouth and then migrate to the stomach, where they attach to the gut lining. They do not usually cause serious health problems but can lead to ulcers within the stomach.

Pinworms

The most common clinical sign of pinworms is a horse that is continuously rubbing its bum. The worms live in your horse’s rectum and exit only to lay their eggs around the perineum. This is particularly itchy, so horses may be seen to itch their hind end on water buckets, feeders, and other objects. Pinworms are a problem for horses housed indoors because they will itch where they eat, and therefore ingest the worms again, continuing the worm’s life cycle. To diagnose pinworms, your veterinarian will use the scotch tape test and look for the eggs under a microscope.

Habronema

Habronema are stomach worms that can cause inflammation of the stomach as well as sores on the skin. These worms have an interesting life cycle and require an intermediate host, or middleman. Horses are infected by ingesting flies that are carrying the larval stage of the worm. These flies can also lay the eggs on your horse’s coat and cause the characteristic “summer sores” that present as yellow or white crust-covered wounds that normally have a blood-tinged draining fluid.

Tapeworms

There are several species of tapeworm, and each species colonizes a different part of your horse’s gut. The most common tapeworm, Anplocephala perfoliata, often causes impactions at the ileocecal junction. This will cause your horse to show signs of colic. Horses may also show signs of unthriftiness and anemia. Gastrointestinal ulceration can occur where the tapeworms attach to the inner lining of your horse’s gut. Eggs are shed in feces sporadically, so they are often difficult to detect from fecal samples. Tapeworms also require an intermediate host, the mite. Once the eggs are passed in your horse’s feces, the mites ingest the eggs, and then your horse will inadvertently ingest the mite when grazing pasture or eating hay.

The Solution

Prevention is key! Fecal egg counts should be performed by your veterinarian in the spring and fall. If your barn has a history of heavy worm burdens, then submitting fecal samples even more frequently may be required. The results of the fecal egg count will determine whether your  veterinarian recommends the administration of a de-wormer. For horses that are shedding low numbers of worms (<200 eggs per gram), your vet will most likely recommend de-worming only twice a year. For high-shedding horses, de-worming more frequently may be required. It is important to be aware that some worms do not always show up on a fecal egg count, such as tapeworm, encysted small strongyles, pinworms, and bots. For bots, Ivermectin should be administered before every winter. Praziquantel works best for tapeworms and should also be administered annually.

veterinarian recommends the administration of a de-wormer. For horses that are shedding low numbers of worms (<200 eggs per gram), your vet will most likely recommend de-worming only twice a year. For high-shedding horses, de-worming more frequently may be required. It is important to be aware that some worms do not always show up on a fecal egg count, such as tapeworm, encysted small strongyles, pinworms, and bots. For bots, Ivermectin should be administered before every winter. Praziquantel works best for tapeworms and should also be administered annually.

It is also important to note that you do not necessarily want a fecal egg count of zero. Even though it may seem counter-intuitive, it is important to keep low levels of worms around that are susceptible to de-wormers. The development of resistance to the various de-wormers has been studied and could cause serious issues for the equine community if veterinarians and owners are not controlling worms appropriately.

You can also help prevent your horse from becoming infested with parasites by routinely picking up manure, rotating turnout, and maintaining good hygiene in the barn. (Read an article on how to compost manure.) That means keeping water buckets and troughs clean, keeping hay stored in appropriate, clean areas, and not throwing hair onto places where horses frequently defecate.

Your horse will thank you!

![[horse innards and parasites]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/sb-horse-diagram.jpg)