A complicated orthopedic surgery performed recently at the College of Veterinary Medicine received assistance from the College of Engineering at the opposite end of the University of Illinois campus.

![[Dr. Nichole Rosenhagen holds the bone models used in the surgery of the bald eagle]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/news-nicki-bones-eagle.jpg)

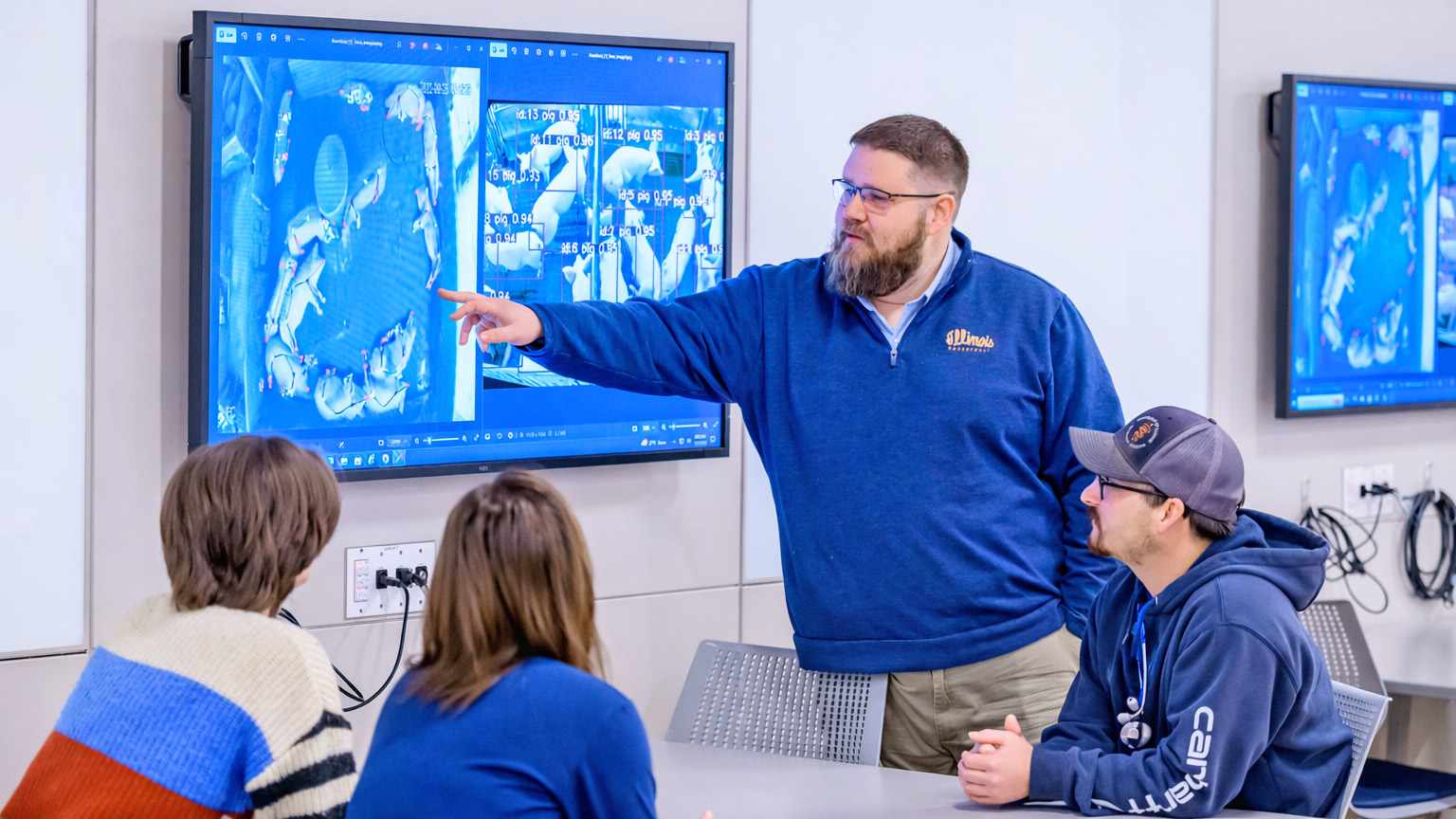

While no engineers scrubbed in for the surgery, they did produce life-sized plastic models of the bird’s healthy right humerus as well as the injured bone. With these two models in hand, Dr. R. Avery Bennett, an acclaimed avian surgeon, had an exact reference for correctly realigning the injured bone. The surgery went well, and the eagle is recovering.

Like the surgery, the process of producing the bone model prototypes was complicated.

First, the massive dataset from the spiral CT scan of the eagle had to be processed by veterinary radiologist Dr. Stephen Joslyn, who consulted from Australia, to “threshold” the data, that is, to tell the computer how to differentiate between “bone” and “not-bone” in the minutely nuanced information generated by the CT.

Because the fragmented nature of the injured bone did not yield a single shape that could be output by the printer, medical illustrator Janet Sinn-Hanlon was asked to use the more powerful software of her trade to manually thicken and link areas of bone. Dr. Bennett reviewed the work and requested that the “good” humerus be printed out for comparison. Wildlife intern Dr. Nichole Rosenhagen facilitated communications among all these professionals.

Unfortunately, when the files were ready for printing on the day before the surgery, the queue for the 3D printer was booked solid.

![[Ralf Möller and Nick Ragano]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/news-eagle-moller-ragano.jpg)

“Ralf arranged for the models to be printed and processed overnight so they would be ready by the time the building opened at 7 the next morning.”

Möller demurs at the claim to heroism, insisting, “Vet Med was already a good customer, and this job had to be done in a timely manner.”

According to Möller, collaborations between the Rapid Prototyping Lab and the College of Veterinary Medicine began a few years ago, when Sinn-Hanlon contacted the lab to produce 3D-printed teaching models.

Dr. Joslyn, a radiologist on faculty at Illinois between 2012 and 2015, also sent many jobs to the lab, printing 3D models of turtle shells used for teaching exercises as well as bone models to aid in the treatment of specific patients at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, from dog limbs, to a skull tumor, to horse limbs. (The horse limbs had to be printed to scale rather than actual size because the printer output is constrained to a ten-inch cube.)

This history underlies the above-and-beyond customer service in overnighting the eagle bones. The eagle bones were sent to the printer as soon as the print queue was free, around 5:20 pm, with an estimated finish time of 11:45 pm.

Möller says undergraduate student Nick Ragano, one of the lab’s “most seasoned” technicians, agreed to visit the lab that night to perform the additional steps needed to make the eagle bones ready.

The material “comes out like a blob,” explains Möller. “Nick used a small pressure washer to wash away the starch-based material that is used as a substrate to support the plastic models, then he dried and packaged the bones for pickup.”

The next morning Dr. Rosenhagen collected the bones, and Dr. Bennett referred to them several times as he set the eagle’s humerus straight.

It is hoped these efforts will enable one lucky bald eagle to once again fly right.

![[digital image on screen and printed bone models in front]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/news-eaglehumerus_images.jpg)