Seizures are a clinical manifestation of excessive hypersynchronous neuronal activity. The causes of seizures are due to an inadequate amount of neuronal inhibition (i.e., GABA and glycine), excessive neuronal excitation (i.e., glutamate) or both. Seizures originate from the cerebrum and/or thalamus.

The four components of a seizure are the pre ictal (prodrome and aura), ictus, and post ictal period. Prodrome is prior to the onset of seizure and may or may not be seen or reported. It may manifest as increased hiding, pacing, or attention seeking. The aura is the initial manifestation of the seizure. It may last seconds to minutes and may be seen as stereotypical motor, behavioral, and/or autonomic changes. Clinically it may be difficult to differentiate between the prodrome and aura and is typically referred to as the pre ictal period. The ictus is the actual seizure event and typically lasts less than two minutes. The post ictal period can last minutes to days after the seizure. Patients may show behavioral and/or neurologic (forebrain) symptoms in the post ictal period.

Epilepsy is defined as recurrence of seizures and typically designated as two or more seizures occurring at least one month apart. Epilepsy is a symptom; it is not a disease. A cluster is defined as two or more seizures within a 24-hour period, with a recovery of consciousness. Status epilepticus is a seizure lasting longer than 5 minutes or two or more seizures without a recovery of consciousness.

Seizures can be classified by the type or etiologic category. The three main types of seizures are focal, generalized, and focal with secondary generalization. The latter is the most common in people and dogs with primary epilepsy. Generalized seizures can be described as tonic, tonic-clonic, clonic, myoclonic, atonic, or absence. Focal seizures are either simple (no loss of consciousness) or complex (loss of consciousness).

The etiologic classification describes the seizures based on two major underlying causes:

1) Idiopathic (otherwise known as genetic or primary) epilepsy

2) Structural epilepsy

Idiopathic epilepsy is a very common neurologic disease, estimated to affect 1 percent to 2 percent of the entire dog population. It can be subclassified into three types (genetic epilepsy, suspected genetic epilepsy, and epilepsy of unknown cause). Seizures are refractory to one medication in about 25 percent of cases. There are many breeds that can be affected with primary epilepsy and a complex mode of inheritance is suspect in most purebred dogs. Genetic epilepsy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Factors that support the diagnosis include first seizure event between 1 and 5 years of age in dogs, normal interictal period and normal diagnostic testing.

Structural epilepsy is characterized as epileptiform seizures due to an underlying intracranial pathology. Possible differentials for structural epilepsy include degenerative, anomalous, neoplastic, inflammatory (infectious or immune-mediated), trauma, or vascular. Extracranial causes of seizures, such as toxins, hypoglycemia, hypoxemia, hepatic disease, renal disease, thiamine deficiency, etc., are considered reactive seizures. In these cases, the epileptiform activity is occurring as a response to a transient disturbance in function of a normal brain.

It is rare to visualize the seizure event. Therefore, we need to rely on the owner’s history of the episode. In many cases, video recording of the event can be helpful. There are many episodes that can mimic seizure (e.g., syncope, vestibular events, head bobbing, sleep disorders, cervical muscle spasm). Therefore, a thorough history and neurologic examination are keys to not missing a diagnosis of a different disease process.

There are three questions we should ask of all cases with the chief complaint of seizures: 1) Is it a seizure? 2) What is the cause? 3) Does it require treatment?

When deciding to start treatment for seizures, we need to consider the disease and treat any underlying issue that may be causing a symptom of seizure, such as detoxification and antibiotics for infectious disease. We also need to consider the kindling phenomenon; each seizure can cause a positive feedback loop and stimulate another seizure. Lastly, we need to consider the patient and client compliance (for example, the difference between medicating a fractious cat versus a food-motivated Labrador retriever). Such factors need to be discussed and decided with the owner.

Maintenance anticonvulsant treatment should be considered required in the cases where there is known intracranial disease, the patient is in status epilepticus, and/or there are two or more isolated events or cluster episodes within a 4-week period. The 2016 ACVIM consensus statement on seizures also recommends starting antiepileptic drug treatment if there are two or more seizures in a 6-month period.

Educating Clients

Client communication is key to success and meeting reasonable expectations for their pet’s treatment. The discussion about seizures and anticonvulsant medications is as important as the discussion you would have with clients about diabetes and insulin treatment.

Clients must understand that seizure therapy is considered successful if there is a 50 percent or greater reduction in the frequency, intensity, and/or severity of seizures. It is unrealistic to communicate to the owners that there will be no seizures. The owners also need to realize that the patient will likely require lifelong treatment with frequent reevaluations and monitoring. They should also be aware that there is the potential for emergency visits and possible side effects of the medications. It is also important for them (and us as the clinicians) to not judge the efficacy of the medication for at least 4 weeks.

Clients should be advised to not change the medication dose without consulting their veterinarian. Unless there is toxicity or other side effects with the medications, it is strongly recommended to wait one year for the patient to be seizure free before trying to decrease the medication.

Owners should be informed that they should not stop the medications “cold turkey,” which could cause the patient to have an increase in epileptiform activity (in other words, cluster seizures or status epilepticus).

Owners should also be instructed to keep a calendar to record the date, time, and duration of the pre ictus, ictus and post ictus periods of every seizure.

At-home Seizures

Owners should be taught what constitutes an emergency. If a seizure lasts 5 minutes or longer and/or the pet has three or more seizures within a 24-hour period, the pet requires emergency evaluation by a veterinarian. After a seizure, the owner should be instructed to administer medications.

Many owners are adverse to giving medications rectally. Unless the patient has a history of cluster episodes, we can avoid the rectal route. The owners should be instructed to give an extra oral dose of their maintenance anticonvulsant once the patient is awake and aware enough to swallow. This works with most seizure medications, except bromide (due to its long half-life).

For patients that tend to cluster, consider a pulse dose and additional short-acting anticonvulsant drug to be administered over 48 to 72 hours after the last seizure. Strategies that allow the owner to administer medications at home to avoid additional seizures can mean that the patients stay out of the emergency room and can ultimately avoid euthanasia.

Treating Seizures in the Clinic

When a patient presents actively having a seizure, initially assess the ABC’s and vital parameters. Hyperthermia and hypoxia are potential complications of status epilepticus. It is also important to try to obtain intravenous access. If you are unable to get intravenous access, you can give diazepam (1 to 2 mg/kg rectally) or levetiracetam (20 to 30 mg/kg subcutaneously or intramuscularly).

Be sure to collect blood in order to rule in or out hypoglycemia, hepatic, and other metabolic diseases. Be sure to collect blood for possible levels before reloading a patient on medications. For phenobarbital, collect blood in a red top without a serum separator.

Once you obtain IV access, administer levetiracetam (20 to 30 mg/kg IV) or a benzodiazepine, such as midazolam (0.1-0.2 mg/kg IV or IM in multiple species), diazepam (0.5 mg/kg IV in dogs or cats), or lorazepam (0.2 mg/kg IV dogs) to most rapidly stop the seizure. If intravenous access cannot be obtained quickly, both diazepam and midazolam can be administered intranasally (same as the IV dose) and diazepam can be administered rectally (at double the IV dose).

Remember that most of the benzodiazepine therapies have a very short duration of action. This is very important, as they can be helpful and quick to stop the initial seizure. Be sure to start the patient on maintenance drug therapy or start loading medications to prevent additional seizures, as the effects of the benzodiazepines wear off quickly.

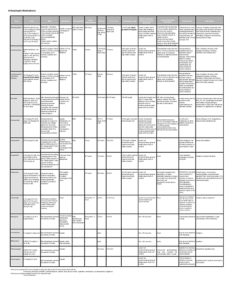

Please refer to the chart regarding the available antiepileptic drug therapy.

By Devon Hague, DVM, DACVIM (Neurology)