When experts at the University of Illinois Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory performed whole-genome sequencing on samples from a 1-month-old goat with diarrhea, they were surprised to find the presence of hunnivirus, which was not previously reported in a ruminant in North America.

Lead virologist Dr. Leyi Wang decided to go looking for other instances of hunnivirus. Working with archived fecal samples from diagnostic laboratories in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Quebec, his team retrospectively screened for the virus in 98 cattle, 38 goats, and 8 sheep. The results, published in the November 11 issue of Viruses, demonstrated the presence of hunnivirus in cattle and goats in North America.

What Is Hunnivirus?

Hunnivirus was initially discovered in sheep cultures in 1965 in Northern Ireland but was not genetically characterized until 2012. Since its official designation in 2013, it has been reported in cattle, goats, water buffalo, pangolins, cats, and several species of rats. Except for one report citing a rat in New York City, none of these studies identified animals in North America.

The clinical significance of hunniviruses in animals remains to be determined. Intestinal illness has been described in only a few animals—cattle, sheep, and cats—with hunnivirus. However, this study, which arose from the discovery of hunnivirus in a goat with diarrhea, supports the idea that hunnivirus could have a link to diarrheal disease.

Takeaways from the Study

Dr. Wang used the hunnivirus sequenced from the month-old goat to design probes used to detect hunnivirus in archived samples from cattle, sheep, and goats. He also analyzed the genetic sequences, revealing two distinct geographic and host-specific lineages in North America.

“This finding suggests that the Illinois goat case arose from an earlier cross-species transmission event,” said Dr. Wang.

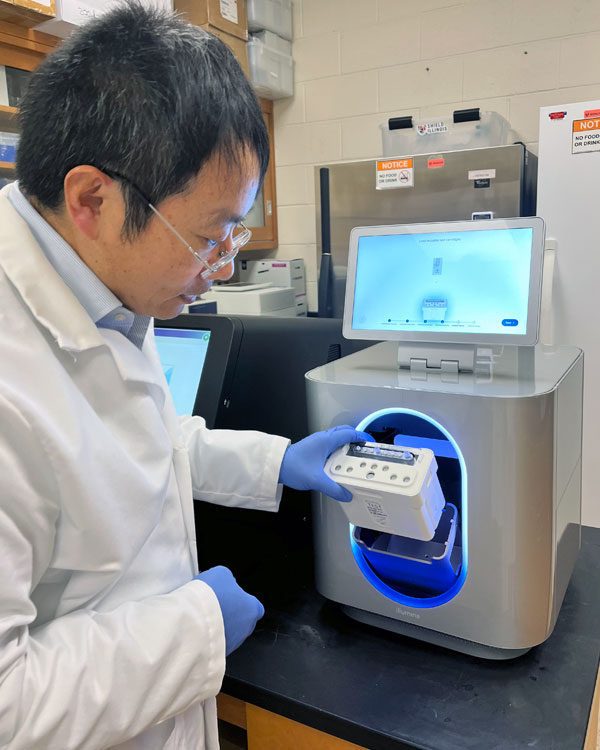

All sequencing was performed at the University of Illinois Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

“Our study expands the geographic range of hunnivirus and suggests the existence of multiple viral lineages in North American ruminants,” said Dr. Wang.

“It also shows that unbiased metagenomic sequencing has a place in veterinary diagnostic investigations. This type of analysis contributes to the discovery and surveillance of emerging viruses in the veterinary field.”

Previously, Dr. Wang was the first to report the presence of bovine kobuvirus in the United States, after sequencing the microbial DNA in samples from infected cows from Illinois. He is currently working on publishing several complete genomes of animal viruses not yet available in public databases.

“Next-generation sequencing (NGS), or whole-genome sequencing, provides a powerful tool, delivering much more robust diagnostics than were possible with previous technologies,” said Dr. Wang. “You can have the whole picture now. It’s kind of like a net. We can catch everything inside of the sample.”