Dr. Carl Toborowsky, a clinical assistant professor in the cardiology service, has degrees in East Asian studies, ecology, evolution, and systematics, and biological anthropology in addition to his veterinary degree from the University of Pennsylvania.

Congenital heart diseases (CHDs) in dogs and cats encompass a range of structural and arrhythmic cardiovascular anomalies present at birth, not all of which are hereditary. Many prevalent CHDs, however, do have either a genetic basis or a breed predisposition, with affected pets having an increased risk of passing these conditions on to their offspring. Examples include patent ductus arteriosus in the poodle, subaortic stenosis in the Newfoundland, tetralogy of Fallot in the keeshond, and tricuspid valve dysplasia in the Labrador retriever (1,2).

Congenital heart diseases can be diagnosed at various life stages, though they are most commonly identified in younger animals at early visits with a veterinarian.

These conditions are categorized broadly into:

- Defects such as intracardiac or extracardiac shunts resulting from improper developmental separation of heart structures

- Abnormal valve morphologies (e.g., valvular stenosis, dysplasia)

- Vascular malformations

The developmental aberrations of the canine heart can lead to a spectrum of disorders ranging from simple to complex, with varying degrees of severity. Clinical manifestations may include cyanosis, weakness, collapse, stunted growth, exercise intolerance, and congestive heart failure. While some pets may remain asymptomatic, others suffer severe clinical signs or premature death.

When to Refer to a Cardiologist

Early detection of a heart murmur in young pets raises critical questions for guiding further evaluation by a cardiologist (3).

- Is a heart murmur present, and does its character suggest a benign murmur or point towards a congenital condition?

- Does the breed of the pet predispose it to specific CHDs?

- Are there any known occurrences of CHD or sudden deaths in the pet’s familial

line? - Are there clinical signs indicative of cardiovascular disease in the pet?

Affirmative responses warrant a cardiologist’s assessment. Initial recognition of

cardiac anomalies by general practitioners is crucial, often leading to timely referrals

for comprehensive diagnostic evaluations.

A heart murmur in a young pet might be classified as “innocent” if it meets specific criteria: a grade of 3/6 or lower, localization at the left apex, occurrence solely during systole, and resolution by six months of age (4).

Murmurs not fitting these criteria may suggest the presence of CHD. Diagnosis generally relies on non-invasive techniques such as echocardiography, though complex cases may necessitate anesthesia and advanced imaging, including CT scans, cardiac MRI, or catheterization.

Management of Congenital Heart Disease

Once a CHD has been diagnosed, the following factors must be addressed prior to any type of interventional management of the defect.

- Anatomy of the heart defect

- Severity and clinical manifestations of the disease

- Patient size (including vessel size for vascular access)

- Presence of concurrent congenital or acquired heart disease

- Presence of concurrent systemic disease

- Need for advanced imaging to characterize the anatomy

- Procedural availability

- Operator experience

- Equipment inventory and availability

- Cost of the procedure

Some forms of CHD require no treatment and may carry a favorable long-term prognosis. Other defects may be amenable to definitive therapy or to some form of palliative treatment.

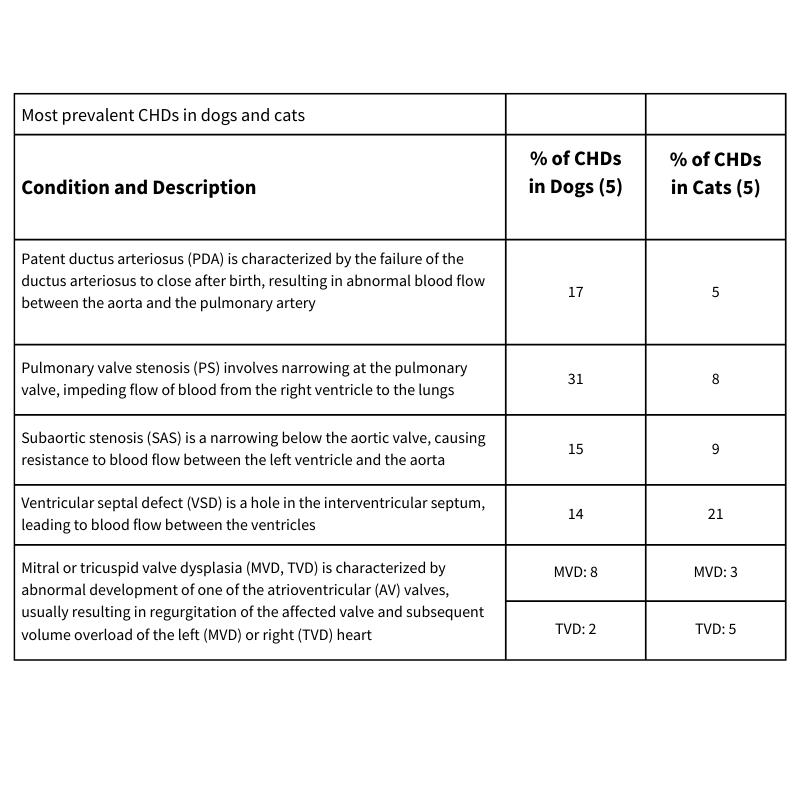

The most prevalent CHDs in dogs and cats are listed in the table below, with their distinctive diagnostic features and their representation among all CHDs in a species, as a percentage (5).

Interventional Procedures

The choice of intervention in CHD largely depends on the type and severity of the defect.

Surgical correction: Can be used to address left-to-right shunting PDA, where the ductus is ligated surgically.

Surgical palliation: When complete surgical repair is not feasible, some surgeries can mitigate clinical signs of CHD, such as creating systemic-to-pulmonary shunts in patients with tetralogy of Fallot (e.g., modified Blalock-Thomas-Taussig shunt) or placing constrictive bands around the pulmonary artery to reduce the degree of left-to-right shunting in cases of atrial or atrioventricular septal defects.

Balloon valvuloplasty, membranostomy, and angioplasty: Often employed for stenotic valvular disease (e.g., PS, AS), vascular disease (e.g., pulmonary artery branch stenosis), or for creating openings across persistent fetal intracardiac structures that should have disappeared before birth (e.g., cor triatriatum dexter), this technique involves the use of a balloon catheter to dilate stenotic valves and vessels and to create fibrous membranes.

Transvascular or transvalvular stenting techniques: In cases where traditional interventional procedures may not be feasible or may yield suboptimal results (e.g., with severely hypoplastic PS), a small stent can be deployed across a narrowed region of valve or vessel to permanently dilate it.

Transcatheter occlusion: Used most commonly for closing PDAs, and to a lesser extent atrial septal defects (ASDs) and VSDs non-surgically, employing occluding devices delivered via catheters.

Hybrid approaches: These procedures combine treatments traditionally available only in a catheterization laboratory with those traditionally available only in a surgical operating room, which allows for a surgical approach combined with image-guided intervention (e.g., direct catheterization of a left atrium for treatment of mitral valve stenosis or cor triatriatum sinister, periventricular occlusion of a VSD, and transatrial ASD occlusion).

These procedures vary in their invasiveness, cost, and required expertise, and not all are suitable for every patient or available in all practice settings (3).

Prognosis and Outcomes

The prognosis for dogs and cats with CHD depends on the specific defect and its severity at the time of diagnosis. Early-detected and promptly treated cases of PDA often have excellent outcomes, with the majority of patients living normal lifespans post-intervention.

However, conditions like severe PS, SAS, TVD, and large VSDs may have a more guarded prognosis, particularly if severe cardiac remodeling has already taken place at time of diagnosis, or if the severity or location of disease is such that it is not amenable to effective intervention.

Lifelong monitoring may be necessary for some conditions. Complications like congestive heart failure may develop, necessitating additional supportive care or medical management.

Overall, CHD in companion animals encompasses a wide range of potential anomalies, each requiring a tailored approach from detection and referral to intervention and long-term management. General practitioners play a crucial role in the early identification and referral of such cases, impacting the overall prognosis and quality of life of patients with these congenital conditions. This complex interplay of diagnosis, management, and follow-up requires maintaining a high level of vigilance and up-to-date knowledge in the evolving field of veterinary cardiology.

References

- MacDonald KA. Congenital heart disease of puppies and kittens. Vet Clin Small Anim 2006;36:503-531.

- Meurs KM. Genetics of cardiac disease in the small animal patient. Vet Clin Small Anim 2010;40:701-715.

- Saunders AB. Key considerations in the approach to congenital heart disease in dogs and cats. J Sm Anim Pract 2021;62:613-623.

- Cote E, Edwards NJ, Ettinger SJ, et al. Management of incidentally detected heart murmurs in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2015;246:1076-1088.

- Schrope DP. Prevalence of congenital heart disease in 76,301 mixed-breed dogs and 57,025 mixed-breed cats. J Vet Cardiol 2015;17:192-202.

By Carl Toborowsky, MS, MA, VMD, DACVIM (Cardiology)