Look no further than the daily headlines about highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) infecting cattle—and potentially the milk supply—to understand the importance of protecting the nation’s livestock industries from disease introductions. The US Department of Agriculture has long prioritized helping states prepare to prevent, detect, and respond to such an outbreak.

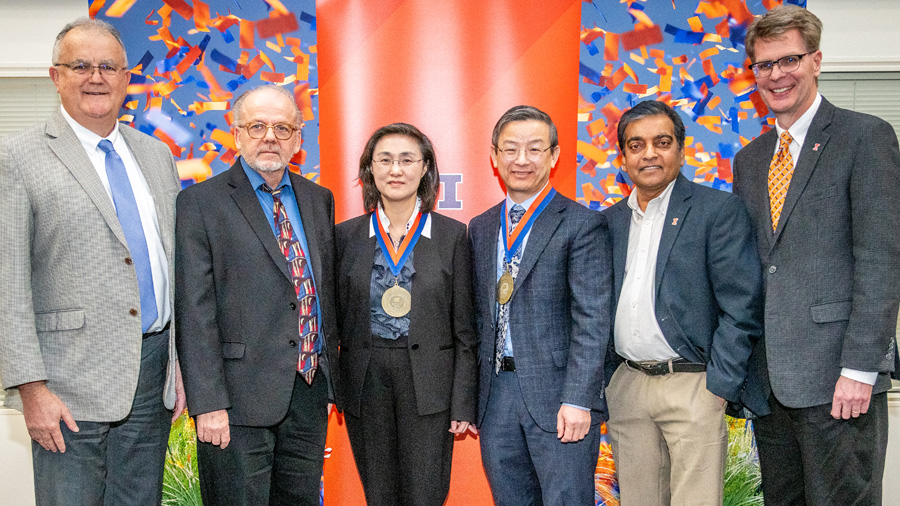

With a grant from the USDA, three faculty members from the College of Veterinary Medicine have recently conducted trainings to better prepare state animal health officials to respond to these types of foreign animal diseases. In March, Drs. Yvette Johnson-Walker, Gay Miller, and Will Sander traveled to New Hampshire to facilitate a tabletop exercise that simulated a coordinated response to an introduction of African swine fever (ASF). ASF is a highly contagious and deadly viral disease that affects domesticated and feral pigs. Though the disease is not currently found in the US, the risk that ASF could reach our shores is ever-present, and that risk increased when ASF broke in the Caribbean in 2021.

The Illinois team hosted 50 participants, including animal health officials from all six New England states, USDA representatives, and personnel from state public health agencies and environmental departments. Through a hybrid format, participants worked online and in person at the New Hampshire Audubon Center in Concord, New Hampshire, to better understand how they would coordinate their response if ASF came to their region. The eight-hour exercise was a big first step in setting up mechanisms needed to coordinate the multifaceted response that would reach into all aspects of the agricultural community.

The Illinois team has led similar trainings in Maryland and Florida within the past year.

Dr. Johnson-Walker, senior lecturer in clinical epidemiology, shared her perspectives on the training exercise:

What seems to be the biggest challenges that groups discover as they work through the exercise problems in real-time?

I think the lessons learned are different for each stakeholder group. Practicing veterinarians, livestock producers, and allied industry representatives are often surprised at the complexity of disease response and the number of agencies and legal authorities involved – state and federal Departments of Agriculture, Transportation, Natural Resources, Public Safety/Law enforcement, Public Health, Environmental Protection, and more depending on the nature of the disease outbreak.

Many animal health regulatory agency personnel have had recent experience in emergency response due to the recent HPAI outbreaks. However, the tabletop exercises provide them with an opportunity to network and plan with the variety of partner response agencies in the absence of an emergency.

We have taken a regional approach to these exercises because regulatory authority often differs across jurisdictional boundaries. Regional exercises provide a low-stress environment for personnel to problem solve across boundaries and enhance response capability. Regional response planning provides an opportunity to share best practices and learn from the experiences of others.

Do you ever learn something new when you are offering the trainings?

I learn something new with each exercise. Although the structure and organization of emergency response has been standardized, each response is unique. For each exercise, we consider the nature of the local livestock production system, animal movements, susceptible wildlife species, feral livestock, transitional farms, cultural differences, recreational activities, and human movements all of which impact the risk of introduction and spread of infectious disease and effective control measures. Even within the same location, these factors may differ substantially across susceptible species.

When working with the zoological community, I learned that sometimes animals in the zoo collection are on loan from another country and that the US Department of State may be involved in decision making and communication about the management of those animals. I also learned that diets for insectivores are often shipped in used egg cartons, which can pose a risk during an HPAI outbreak.

When exercising potential ASF outbreaks, I learned about transitional swine rearing operations and licensed garbage feeding, which is permitted in some states. I also learned about the challenges of managing animal movement when there are local therapy pigs, companion pigs, feral hogs, and commercial swine in a single region.

What is important for the general public to know about how our government and public health/veterinary leaders prepare to address a food animal disease outbreak?

I think it is important for the general public to know two things. The first is that preparation for an animal health emergency is a continuous process. Animal health regulatory agency personnel from state and federal agencies are always looking for ways to improve our response capabilities, communicate effectively with stakeholders, and enhance the resilience of producers in the face of an outbreak. The second is that…

“Everyone has a part to play in reducing the risk of introduction and spread of disease impacting livestock health and welfare.”

Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker

Animal owners (livestock or companion):

- Provide regular veterinary care for your animals, keep them up to date on immunizations and parasite control, notify your veterinarian of unexpected illness or deaths among your animals.

- Practice good hygiene and biosecurity to avoid introducing disease and spreading pathogens to household members.

Travelers:

- When entering the US, declare all agricultural or wildlife products to US Customs and Border Protection officials and notify them if you visited a farm or were in contact with animals while abroad.

Outdoor enthusiasts, hunters, hikers:

- If you find sick or dead wildlife, contact your closest state or federal wildlife agency; they can decide whether to investigate. You might also contact your local health department to report this occurrence.

Has the fact that the world went through a pandemic had any impact on how teams are responding to this disease-response training?

I have been working on this issue since the 2001 outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the UK. A lot has changed since then. In the past there was less interest in preparing for something that had never happened. Many people were convinced that we would not face a large-scale infectious disease outbreak in our lifetime. The experience of widespread outbreaks of HPAI in poultry and the rapid spread of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus has changed that perspective. Everyone is recognizing that the issue is not IF we will experience a widespread infectious animal disease outbreak but WHEN. Now people are much more willing to take the time to prepare for a potential outbreak.

“One of the big lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic is just how interconnected and interdependent we are. “

Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker

Even though domestic livestock were not susceptible to the disease, the devastating impact of it on the human population had a great impact on livestock, especially poultry and hogs. We also learned the importance of response plans that consider supply chain disruptions. After facing these widespread outbreaks of human and animal disease, emergency response planners are also much more aware of the mental health cost of disease response. Livestock producers, regulatory agency personnel, private veterinary practitioners, and the general public experience mental health consequences when animals are depopulated to prevent spread of disease.