Myasthenia gravis (MG) is termed a “neuromuscular” disease.

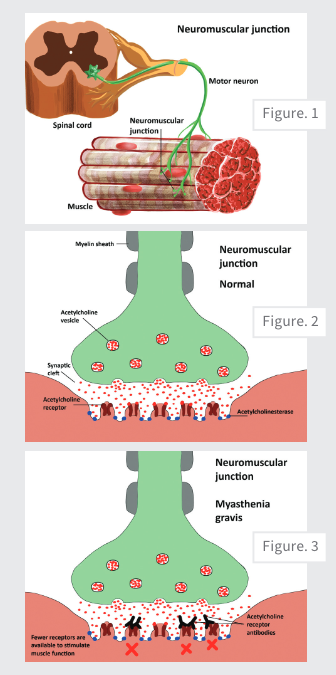

When an animal needs to execute a motor function, such as standing up and walking, neurons will send signals directly to the muscle fibers for contraction. The point at which the neuron communicates with the muscle is called the “neuromuscular junction” (Fig. 1).

When stimulated, the neuron will release a little “packet” of acetylcholine (ACh) chemical into the neuromuscular junction space. The ACh will bind to receptors on the muscle, which will trigger the muscle to contract and do its job. In the neuromuscular junction area, acetylcholinesterase enzyme will degrade any extra ACh to prevent muscles from doing too much and getting too stiff and spastic (Fig. 2).

This entire process helps us to get up and run around but without too much muscle stiffness and rigidity. We can relax quickly and easily when we need to and then be ready at a moment’s notice to act again.

In adult dogs, MG is most often an auto-immune disease (“acquired myasthenia gravis”) in which the body attacks the receptor proteins in the muscle of the neuromuscular junction (Fig. 3). This prevents the ACh from being able to bind. When it cannot bind, then it cannot stimulate the muscle to contract.

Animals then get very weak and tired because the muscles aren’t able to react as quickly and strongly as they normally do. While the receptors do regenerate, they don’t regenerate fast enough to keep dogs feeling strong and healthy without medical intervention.

Clinical Presentation of MG

Acquired MG can present in one of three syndromes.

- Generalized Myasthenia

Animals can have exercise intolerance. Although these patients may seem normal after a period of rest, they can slow down, start to look weak, and may need to sit or lie down as they walk farther or play longer. This is due to weakness in the trunk and leg muscles. This syndrome is also often accompanied by regurgitation (which can sometimes be confused with vomiting) due to weakness of the esophagus muscles.

About 50% of all MG cases take the generalized form. Of these cases, 70% to 85% will have additional bulbar signs, e.g., megaesophagus. - Focal Myasthenia

Instead of body weakness, the disease may focus on one smaller part of the body, such as the esophagus. These animals may walk relatively well but can have frequent regurgitation and sometimes changes in voice or weakness of the face muscles.

About 20% to 47% of MG cases are in the focal form. About 30% of all cases of megaesophagus are diagnosed with MG. - Fulminating Myasthenia

This is a very rare, aggressive form of the disease in which an animal might rapidly develop paralysis of the entire body. Studies have reported between 3% and 22% of cases take this severe form, with rapid onset of tetraplegia, absent spinal reflexes, and megaesophagus.

Acquired myasthenia cases, whether manifesting as generalized, focal, or fulminating, can be categorized into the subgroups “seronegative” and “thymoma-associated.”

Diagnosis of MG

Diagnosis usually involves three core tests.

- Neostigmine Challenge

Neostigmine is an injectable form of the medication that we use to treat this disease. Animals with myasthenia are exercised to the point of being very tired and weak, then this medication is given intravenously. When this rapidly returns an animal to more normal strength and walking function, then this is suggestive of myasthenia gravis.

False positive and negative results are possible. About 80% of patients that respond to the neostigmine challenge test will also have a positive acetylcholine receptor (AChR) antibody titer.

Note: Neostigmine injections carry the risk of a cholinergic crisis (CC), which can contribute to life-threatening signs such as bradycardia and respiratory arrest. Consider the following steps.- Calculate a dose of atropine or glycopyrrolate in the event of CC and have the drug readily available.

- Place an IV catheter and be sure you have supplies for intubation and general resuscitation readily available.

- Calculate 0.01-0.04mg/kg of neostigmine.

- For dogs, start at 0.02mg/kg IV or IM

- For cats, start at 0.01 mg/kg IV or IM

- Give the initial dose of neostigmine and wait 15 minutes. Look for signs of improving strength and other signs of cholinergic function, i.e., salivation, lacrimation, urination, and defecation (SLUD). If there is no response and no SLUD signs, repeat the dose once.

- Monitor pets for 2 to 3 hours to ensure no serious complications develop.

- AChR Antibody Titer

This is a more definitive test that we use to rule in myasthenia gravis. This is a blood test that measures the level of antibodies against the AChR. Normal animals should have scant to no measurable antibodies.

Between 2% and 20% of cases are seronegative. In these cases, diagnosis is based on clinical signs, ruling out other diseases, and response to pyridostigmine. Many of these cases may have a positive titer when rechecked in one month.

Be aware that immunosuppressive medications can decrease the antibody titers in the face of active disease. - Thoracic Radiographs

Radiographs of the chest are routinely performed to assess for the presence of megaesophagus (70% to 85% of generalized cases) and aspiration pneumonia (about 50% of all cases).

Between 30% and 50% of animals with a thymoma will develop myasthenia gravis.

Treatment for MG

Any underlying comorbidities, such as thymoma, other neoplasias, infections, and endocrine imbalances, should be treated. Remission of thymoma-associated MG is unlikely without full surgical excision.

The cornerstone of therapy involves treatment with drugs that block the acetylcholinesterase enzyme. This prevents the breakdown of ACh. When more ACh stays in the neuromuscular junction area longer, then it is easier to find a few receptors on the muscle that might not be damaged and can accept the ACh to trigger muscle function.

Pyridostigmine (Mestinon) is an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. When dogs are treated with the right dose, they are usually able to run and play like normal. However, it is rare to cure the megaesophagus component (5% to 15% remission). So even when dogs seem like they are walking and running well, they are still prone to regurgitation and aspiration events.

Animals should show significant improvement within the first week of using pyridostigmine. If this medication is not helping enough despite reasonable adjustments, then we can consider adding medications to try to suppress the immune system. Common choices include a steroid or drugs with fewer side effects, such as azathioprine or mycophenolate.

These medications could reduce the level of circulating antibodies and reduce damage to the muscle receptors. If the immunosuppressive drugs do their job, then the antibody titer might reduce enough to be normal.

Note: The presence of aspiration pneumonia and infections contraindicate immunosuppressive therapy. Additionally, high doses of prednisone can exacerbate general muscle weakness.

The more common side effects from prednisone include increased thirst, needing to urinate more often, weight gain, more pronounced hunger and trying to eat inappropriate things, panting, muscle wasting, and sometimes stomach upset. The thirst and hunger can predispose animals to aspiration when they are prone to gobbling food and water and doing a lot of scrounging.

Treatment plans cannot rely on medications alone. Attention must be paid to crucial supportive care.

- Safe Feeding. Safe feeding in animals with megaesophagus and laryngeal/pharyngeal weakness may require experimentation with different consistencies of food to aid in reducing regurgitation. Dogs can be trained to a special Bailey chair for elevated feedings using gravity to help move food and water into the stomach. Alternatively, some animals may tolerate being held upright by their owners for 15 to 20 minutes after meals.

Calorie requirements should be calculated and daily nutritional needs should be delivered via several small meals throughout the day.

Similarly, hydration needs should be calculated and water delivered with meals in the upright position. In my personal experience (I suffer from an esophageal disorder), food is best moved to the stomach with smaller bites alternating with frequent swallows of water to help move food through the esophagus.

If animals have trouble keeping down plain water, hydration can be supplemented with a semi-solidified form of unflavored gelatin (like Knox) mixed with water or low sodium chicken broth. - Monitoring. Environmental management and close supervision are imperative to be sure that animals do not eat or drink outside of the elevated feedings. This requires restricting access to water and food bowls, not allowing unsupervised snacks or grazing, and closely monitoring animals on walks/outside. The most common cause of death from MG is aspiration pneumonia and respiratory failure. It is crucial to try to prevent this to the degree possible.

- Physical Therapy. Physical therapy may be considered for weak animals to help improve muscle strength.

- Veterinary Visits. Routine monitoring should include periodic recheck examinations to ensure the pet is progressing as expected. AchR antibody titers may be rechecked every 3 to 6 months until negative. Once blood titers have returned to normal when the animal is not immunosuppressed, then medications can be weaned off over 4 to 6 weeks with close monitoring for relapse.

Prognosis

Research has reported that the myasthenia condition will go into remission in 60% to 90% of dogs treated only with pyridostigmine. Depending on the report, the average time to serological remission ranges from 6 months to 2 years. Animals with generalized MG and without megaesophagus have the best chance for full remission.

The overall 1-year mortality rate for MG is 40% to 60%. Animals with megaesophagus, thymoma, or older age may have a more guarded prognosis. According to a recent report of 167 MG cases, median survival for animals with generalized MG was 378 days, focal MG was 78 days, and thymoma-associated was 7 days. Prognosis for fulminating MG is very poor to grave.

How Might Cats Differ from Dogs?

- Cats are less likely to have megaesophagus as a feature of generalized disease: between 15% and 40%.

- Cats are less likely to have focal myasthenia: 10% to 15%.

- Cats are more likely to go into remission, even without treatment (though overall

survival/euthanasia rates appear to be similar to dogs). - Cats are more sensitive to the effects of pyridostigmine and neostigmine. Start with ¼ to ½ of the doses you would use for dogs.

Titus’s Story

Titus presented with a 2-week history of regurgitating and progressive weakness. By the time he arrived for evaluation, he had difficulty walking even a few steps without assistance. He had the most typical presentation for this disease with moderate generalized weakness (rest required for independent ambulation) and moderate bulbar signs (frequent choking or regurgitation). This video shows the characteristic exercise intolerance with the very short strides and tendency to sit down:

In the second half of the video, you will see the neostigmine challenge in which we demonstrated that Titus could not stand to walk on his own. By about 10 minutes after receiving an IV dose of neostigmine, he was able to stand to walk several laps in the room without support. This dramatic improvement was suggestive of myasthenia gravis. The disease was confirmed with a blood acetylcholine receptor antibody titer of 2.62mmol/L (normal is <0.6mmol/L).

As always, if you have questions about myasthenia gravis or any other neurologic condition, the University of Illinois veterinary neurology/neurosurgery team is available to help guide you.

Titus was also confirmed to have megaesophagus. He was treated with pyridostigmine with resolution of his body weakness, though his megaesophagus persists. This video shows Titus during one of his rechecks, and you can appreciate his more normal body strength and overall energy:

To date, Titus still has an elevated blood titer, which suggests persistently active disease. Because he is strong and happy on the pyridostigmine and he is prone to bouts of pneumonia, we have elected to continue his current therapy rather than immunosuppressing him. He has a very attentive family who has helped to give him a very comfortable life with this condition. We wish him many more years to come!

Further reading:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jvim.70113

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jvim.15855

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34331481/

By Rose Peters, DVM, CVA, DACVIM (Neurology)