Cataracts are an ocular disease often diagnosed by primary care veterinarians. Commonly, they are incidental findings, as part of an annual wellness examination. Additionally, owners may have varying knowledge of this disease, as they themselves may have dealt with cataract surgery. Understanding when to start topical anti-inflammatory therapy and when to refer a patient for cataract surgery (phacoemulsification) is all part of being a well-rounded primary care veterinarian.

Cataracts are an opacity within the lens that scatters light. This causes the light to not be focused onto the retina, resulting in cloudy vision. Additionally, since light is still able to pass through a cataract, animals with cataracts will maintain a pupillary light reflex. This is important, because patients that have cataracts and no pupillary light reflex likely have retinal disease.

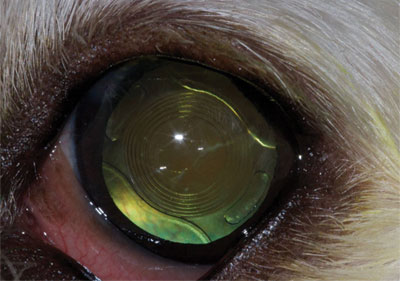

Cataracts have different stages and locations within the lens. Cataract stages include incipient (<15%), immature (16% to 99%), mature (100%) and hypermature. Common cataract locations within the lens include cortical and nuclear. Cataract stage and location within the lens determine the level of vision that the patient has.

Cataracts that are greater than an incipient will often cause lens-induced uveitis (LIU). Additionally, LIU increases as the cataract mature, with 100% of mature/hypermature cataracts having LIU. While LIU may be minor initially for many patients, over time secondary changes occur within the eye.

The development of posterior synechia, iris bombe, and a pre-iridial fibrovascular membrane (PIFVM) leading to glaucoma are potential secondary complications that can arise from LIU. This is why it is important to start a topical anti-inflammatory medication. Even low doses of these medications can have a significant impact on mitigating the damage caused by LIU. Once glaucoma occurs, the success rate of cataract surgery plummets and enucleation starts to be discussed.

Referral to an ophthalmologist is always an option. During the evaluation process, a full ophthalmic examination, including minimum database, will be performed. The ophthalmologist looks for LIU, adhesions, and fundic changes. If the severity of uveitis has led to secondary changes, medical therapy is indicated with no further testing. If phacoemulsification surgery is pursued, pre-surgical testing is performed.

Additional tests include an electroretinogram (ERG) and an ocular ultrasound. The ERG evaluates retinal function and can be performed without sedation. The patient is kept in a dimmed room and three small probes are attached to the head. The patient receives light flashes, and the resulting waveform informs us of retinal function. Ocular ultrasonography ensures that a retinal detachment, posterior lens capsular rupture, or other structural change is not present. Passing both tests is required for surgery.

Phacoemulsification surgery in animals is performed in a similar manner to human cataract surgery. An incision is made within the cornea and the anterior chamber is re-inflated. A small circular incision is made to remove the anterior lens capsule. Next, phacoemulsification removes the cataractous lens material. The lens capsule is then polished, and an artificial lens is placed.

Unlike in human ophthalmology, a uniform lens power is utilized across all canine patients. Additionally, while the goal is always to place an intraocular lens, this is not always possible. Aphakic animals are still visual but far-sighted. While the patients should be visual upon waking up from anesthesia, sedation and use of the E-collar will often give the perception that the animal is still non-visual.

Being able to recognize a cataract and intervene with a topical anti-inflammatory is imperative for primary care veterinarians. Even if surgery is not an option, keeping the patient comfortable and free from secondary diseases, such as glaucoma, is important.

By Todd Marlo, DVM, MS, DACVO