Endodontic disease is one of the most common oral lesions that a veterinary dentist, or any small-animal veterinarian, will see.

The typical cause is traumatic fracture of a tooth that results in pulp exposure, often when chewing on a hard toy or from a forceful impact. Other causes include a blunt trauma that injures the pulp without fracturing the hard tissue and anything that impairs the perfusion of the pulp, such as tooth avulsion. The pulp does not need to be completely exposed to cause pulpitis; near exposure is enough.

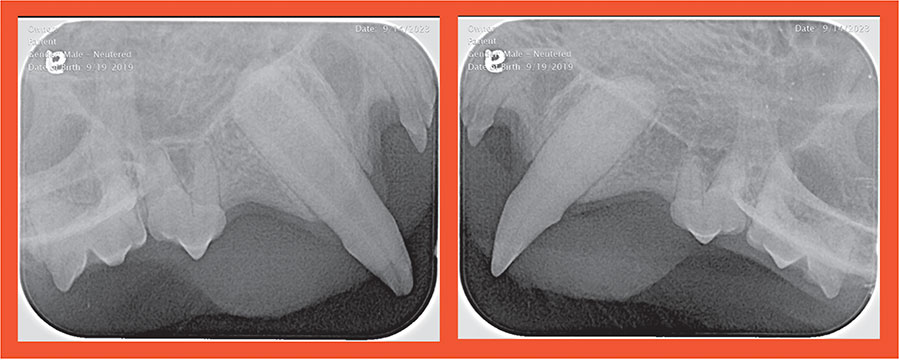

endodontically diseased mandibular

first molar.

Clinically, endodontic disease will present with a variety of signs: you might see pulp exposure, dramatic discoloration of the tooth, facial swelling around the tooth, ophthalmic or nasal signs, and draining tracts in the skin or oral mucosa in chronic cases.

Radiographic signs, such as periapical lysis or a relatively wide pulp chamber can be seen in the absence of gross signs and by themselves serve as an indicator to treat. (The image above depicts radiographs of the maxillary canine teeth from the same patient on the same day. The wide pulp chamber of 104 (left image) is inconsistent with the patient’s age and the pulp chamber in 204. This is indicative of long-standing endodontic disease.)

The pulp chamber of the dead tooth does not get wider, it stops getting smaller like the vital teeth.Treatment is straightforward, but there are subtleties to any case that should be considered when deciding among options. Doing nothing is never acceptable.

Extraction or Root Canal

If a case presents with acute signs, such as facial swelling, and definitive treatment in a timely manner is not feasible, then the lesion can be addressed with antibiotics. This is a temporary fix and treatment should not be cancelled following resolution of the signs. If antibiotics provide only minimal change, then a lesion other than endodontic disease should be considered, especially in an older patient.

Treatment via surgical extraction provides a safe, reliable, and fast option for this condition. Extraction of the tooth will eliminate the source of the infection, and the patient’s immune system will be able to overwhelm and heal the site in the face of residual contamination.

Some clients, such as those with working or show animals, want to preserve the tooth for functional, aesthetic, or personal reasons. In these cases, standard endodontic therapy, or “root canal,” is the treatment of choice. A root canal involves debriding and sterilizing the pulp chamber, followed by filling the chamber with an inert material, then sealing any opening in the crown with composite.

Root Canal Considerations

The procedure is reliable, but there are some considerations that must be made before the client commits to it:

- Unlike extractions, a root canal requires repeated follow-up in the form of annual radiographs. Root canals can fail, and radiographic monitoring is required because the patient won’t inform us of the discomfort.

- A root canal is not a magical shield for the treated tooth. It can be fractured in the future, requiring some form of re-treatment.

- A very young animal (less than a year) is not a candidate for a root canal if the apex is still open.

- The treated tooth will not mature and strengthen like a vital tooth. If a tooth is thin and fragile when treated, it will stay that way.

- A tooth that has little functional crown remaining or is periodontally compromised by the fracture might not be a good candidate for endodontic therapy.

- A root canal is usually significantly more expensive than extraction and might not be fully covered by insurance.

Treating these painful lesions is rewarding and can provide a dramatic improvement to a patient’s quality of life.

By William Krug, DVM, DAVDC