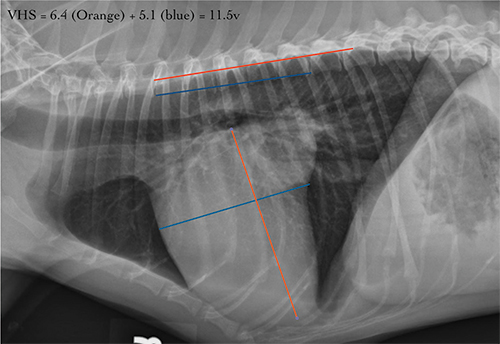

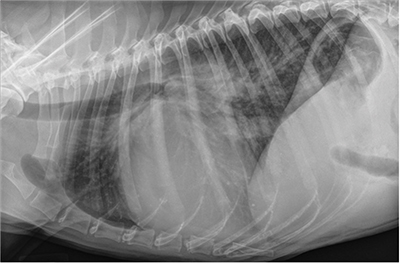

Fig. 1. A dog with moderate cardiomegaly with a VHS of 11.5. There is evidence of left atrial enlargement. The pulmonary vessels and parenchyma are unremarkable with no evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema.

Thoracic radiographs are an important tool for assessing pulmonary pathology as well as overall cardiac size. Quantification of cardiac chamber size by radiography or echocardiography is pivotal for clinical management of cardiovascular disease. It provides a reliable noninvasive estimate of the hemodynamic burden and disease severity.

Echocardiography represents the clinical reference standard for assessment of cardiac chamber size; however, the required access, knowledge, and skillset to operate and interpret echocardiographic examinations might not be accessible or affordable for some. While thoracic radiography is more accessible and affordable, its use to assess cardiac size unfortunately often result in subjective or qualitative results that can contribute to inaccurate conclusions with respect to cardiomegaly.

Many studies, one as recently as November 2021, have proven that qualitative assessment of individual cardiac chamber enlargement is error prone. Results from Huguet et al. showed that even among radiologists with >10 years of experience, subjective identification of left atrial and left ventricular enlargement was only 44% and 26% specific, respectively. Importantly, in the same study, the sensitivity was 97% and 99%. Taken together, this indicates that while thoracic radiographs are a good screening tool, subjective evaluation results in a high number of false positives and could result in overtreatment and erroneous staging.

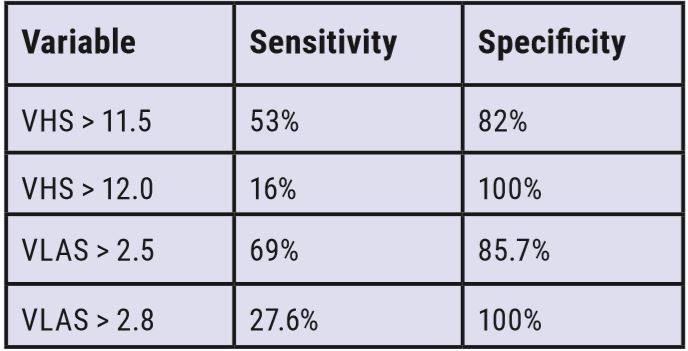

To improve accuracy of assessing cardiac chamber enlargement, surrogate quantitative radiographic measurement of cardiac size such as vertebral heart size (VHS) and vertebral left atrial size (VLAS) are useful. In fact, both VLAS and VHS are useful predictors of echocardiographic heart size in dogs with subclinical myxomatous mitral valve disease (MMVD) when echocardiography is unavailable.

The objectives of this update are to review the techniques for measuring and interpreting both VHS and VLAS, provide meaningful cutoff values that can used in clinical practice, and review the radiographic diagnostic criteria for left-sided congestive heart failure in dogs and cats.

How to Perform a VHS

Please note that computer-based algorithms for automated VHS have not been validated in veterinary medicine and these values MUST always be verified via manual measurement.

1. Take a lateral view of the dog’s heart (right lateral).

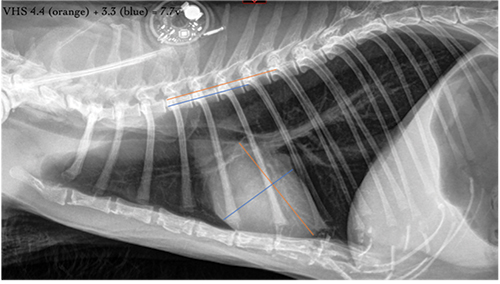

2. Measure the long axis, the length from base (ventral margin of the carina) to apex (L), and the short axis, width of the heart perpendicular to the length measurement, typically at the ventral margin of the caudal vena cava(S).

3. Take these dimensions and scale them against the length of the vertebrae dorsal to the heart, beginning with the fourth vertebral body on the spine (T4).

4. Count how many vertebral bodies the length (L) of the heart is and how many bodies can be included in the width (S) measurement. A vertebral body consists of the vertebral body starting at the cranial endplate and includes the disc space immediately caudal to the vertebrae.

5. If the sum of these two measurements is higher than 10.5, the dog may have an enlarged heart.

6. *There are many breed-specific ranges, and they should be used when available.

Normal VHS for dogs = 8.4 to 10.5* Normal VHS for cats is < 8.1

How to Perform a VLAS

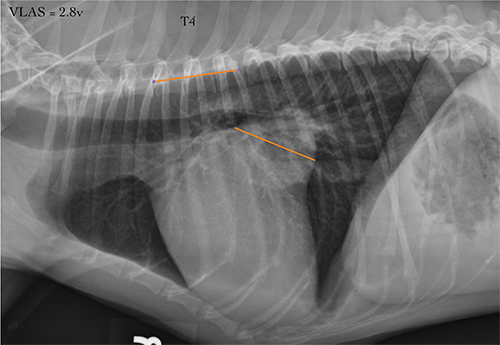

1. VLAS measures the LA size on a right lateral projection.

2. Measure from the ventral margin of the carina to where the dorsal border of caudal vena cava and caudal cardiac silhouette intersect.

3. Take the dimension and scale them against the length of the vertebrae dorsal to the heart, starting from the cranial aspect of the fourth thoracic vertebra (T4).

4. If the measurement is higher than 2.3, it may indicate left atrial enlargement.

Normal VLAS for dogs = 1.8 – 2.3 VLAS has not been validated in cats

Can Radiographs Predict Echocardiographic Left Heart Enlargement?

It is well established that dogs with advanced stage MMVD benefit from pimobendan therapy. Elucidated from the pivotal EPIC trial and emphasized in the ACVIM consensus guidelines for the management and staging of MMVD, dogs with preclinical Stage B2 have a risk reduction of 33% when started on this medication and a significantly prolonged time to heart failure. Vitally, this benefit is associated with a reduction in heart size and prior to significant cardiomegaly there is no benefit.

As such, the ACVIM consensus criteria recommends an echocardiogram for all dogs to accurately confirm Stage B2. Realistically many owners will not pay for or have access to this diagnostic test, placing an unfair burden on general practitioners to accurately stage these dogs. Fortunately, both VHS and VLAS have been proven to be powerful predictive surrogates for echocardiographic left heart enlargement in dogs with preclinical MMVD.

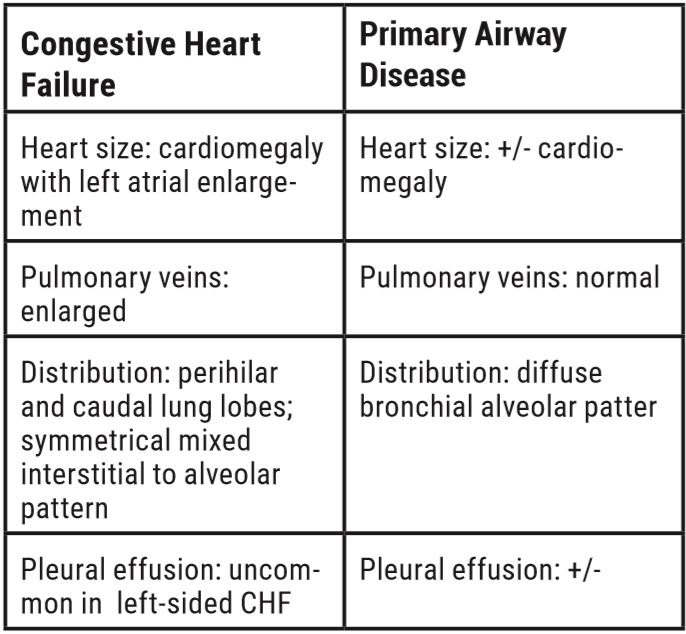

Coughing Dogs: Is It Heart Failure?

The most important diagnostic approach to chronic cough involves history, physical examination, and chest radiographs +/- a heartworm test, if the dog is not on a heartworm preventative.

Coughing and Dyspneic Cats: Is It Heart Failure?

Cats rarely cough from pulmonary edema but do from bronchitis, asthma, heartworm, lungworms, neoplasia, and foreign bodies. Feline bronchial disease (including “asthma”) is the most common cause of coughing. Cats in heart failure will generally present with tachypnea and dyspnea.

Reference

1. Huguet EE, Vilaplana Grosso F, Lamb WR, et al. Interpretation of cardiac chamber size on canine thoracic radiographs is limited […]. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2021 Nov;62(6):637-646. doi: 10.1111/vru.13006. Epub 2021 Jul 22. PMID: 34296488.

By: Saki Kadotani, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Cardiology) and Ryan Fries, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology)