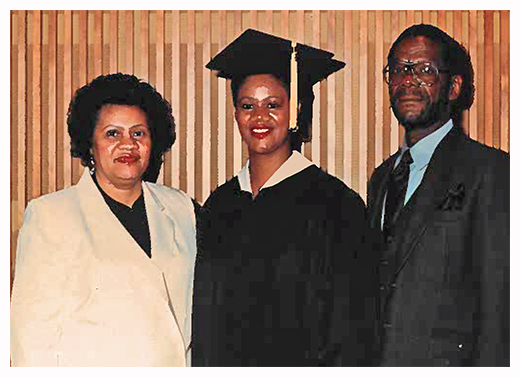

When she earned her DVM in 1989, Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker was only the third person of color—and the first Black woman—to graduate from the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, which graduated its first class in 1952.

Her career path has taken plenty of unanticipated turns. At each step, she was drawn to choices that would be of the greatest help to people. Today, after 17 years as a college faculty member, she can see a lot of positive change in diversity and inclusion here.

“It’s been a slow and gradual process, but there’s been a culture shift,” says Dr. Johnson-Walker. “Now the importance of change is top of mind, and there are a lot more allies. I believe we will continue to make sustained progress.”

In 2018 she was named to the newly created role of Coordinator of Diversity and Inclusion at the college. In some ways, the appointment simply formalized work she had been doing since she arrived at the college as a student.

The Typical Start

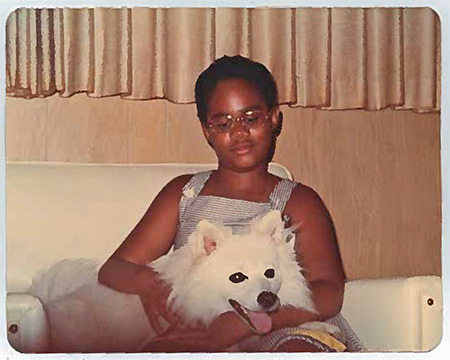

Like thousands of other little girls, Dr. Johnson-Walker aspired to a veterinary career at a young age. She really liked science and liked working with animals. When she was in middle school, her parents broke down and got her a dog.

“Our veterinarian was Dr. Charles Flennoy, a graduate of Tuskegee University,” she recalls. “I had an African American man as a role model.”

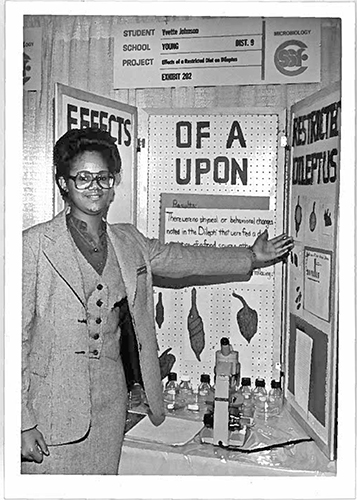

Despite the urging of family and teachers to consider human medicine, she was steadfast: “I thought I’d miss working with animals.” When a teacher gave her the James Herriot books to read in middle school, she was hooked on the idea of being a veterinarian.

Being the Only, Part 1

Dr. Johnson-Walker came to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign as an undergraduate in the animal science program, planning to bolster her large animal experience. Only three other Black students started the pre-vet program with her, and only she and one other completed the degree.

As an undergraduate, however, she had many opportunities outside of class to connect with a support network on campus. When she was a veterinary student, that changed. She was the only Black student in a program that required her engagement “all day, every day.” She had to develop other strategies to survive.

“I learned to find mentors who didn’t look like me,” she says. “And I made lifelong friends with my classmates.”

At the time, many Black students from the Chicago area chose Tuskegee over the University of Illinois to become a veterinarian. They didn’t want the added pressures of an isolating cultural climate on top of the other stressors of vet school.

Vet school is hard and stressful, but it gets better. Create your own success. Success will look different for each of you, and that’s OK.

Yvette Johnson-Walker, DVM, MS, PhD | Coordinator of Diversity and Inclusion

But Dr. Johnson-Walker viewed the opportunity differently: “I chose Illinois because, if no one ever accepted the offer of admission, nothing would ever change. I decided to take on the challenge.”

Drawn Away from Her Original Course

Her Illinois veterinary education also changed her. She started with the goal of practicing small animal medicine in Chicago. Then she gained an appreciation of the One Health concept and began to see how impactful animals are to the survival of low-resourced producers in developing countries.

“I remember walking to class one day with a graduate student from Africa,” Dr. Johnson-Walker says. “When he learned I was studying to be a veterinarian, he said, ‘Wow, you could really help a lot of people.’”

She developed an interest in poultry, a course taught by Dr. Deoki Tripathy. “You can be a landless refugee, but if you have a couple of chickens, they could make it possible for you to send your kids to school.”

By the time she graduated, she was not merely the only Black veterinary student at the college. She also felt she was the only one who didn’t want to go into practice and who wasn’t sure what she did want to do.

Off to Africa, and East Lansing

Dr. Fred Troutt, then head of the Department of Veterinary Clinical Medicine, offered a new path. He suggested she pursue a master’s degree through a grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). She spent a semester at Egerton University in Kenya researching constraints to increasing milk production in small-holder dairy farms. This is also where she fell in love with epidemiology.

While a master’s student at the Illinois veterinary college, she devoted time to advancing diversity. With Dr. Lloyd Helper and Nancy Bailey, associate and assistant deans respectively, in the Office of Academic and Student Affairs, she helped develop an applicant assessment program. The program drew upon the research of Dr. William Sedlacek to identify non-cognitive survival skills—such as resilience, problem solving, goal setting, and willingness to seek help—that are associated with the success of under-represented minority students at predominantly white institutions.

After completing her master’s, she went to Michigan State University for a PhD. The diverse community she found there made a very big difference for her as a student.

“There were people of color in every role: house officers, faculty, and staff. My adviser was an African American. And two Black faculty members who were at MSU while I was have since become deans of veterinary colleges: Dr. Willie Reed at Purdue and Dr. Ruby Perry at Tuskegee.”

Being the Only, Part 2

Her situation changed again when she accepted her first faculty position in the Department of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Maryland. There she conducted research on the environmental impact of commercial broiler production and infectious disease management on broiler farms.

Meanwhile, her lived experience was at various times a study of the environmental impact of being the department’s only woman, only African American, only single parent, and only person without a stay-at-home partner.

“At that time the university required every search committee to include a woman and a person of color. So I was a ‘twofer’ and I served on a lot of searches, including many that were far outside my field,” says Dr. Johnson-Walker.

“I’d be asked to host a candidate for breakfast on the College Park campus that was a 2-hour drive from my workplace in Salisbury, Md., on the eastern shore. Of course, that’s also exactly when I needed to be getting my children to daycare.

“I didn’t feel empowered to advocate for myself at that time,” she recalls. “And it probably never occurred to my colleagues that my situation made it difficult for me to take on work commitments that they could do with ease because they had someone else managing family commitments.”

Dr. Johnson-Walker remained in Maryland for six years.

Back to Illinois

In 2005 Dr. Ron Smith contacted Dr. Johnson-Walker to encourage her to apply for the faculty position in epidemiology that would be opening at Illinois when he retired. Motivated in part by the desire to live closer to her mother, who was in Chicago, Dr. Johnson-Walker did. She was hired and has been here ever since.

Just as it had been in her veterinary and master’s student days, one of her roles at Illinois has been to “be the voice in the room, to have conversations with those who, because they are not directly impacted, aren’t aware of other perspectives.”

And just as it had been at Maryland, the academic career ladder at Illinois was not easy to navigate as a single parent. She didn’t often have the opportunity to attend conferences or work late at the office. But she did find time to talk with students who were struggling.

Message to Students

Dr. Johnson-Walker shares her “lessons learned” with veterinary students.

“When accepting your first job, consider the culture. Will it be conducive to who you are? To all of who you are?”

She advises students to tell a prospective employer when they see that the culture is not a good fit, and to explain why it is not a good fit. “They might make changes for you,” she says, “but even if they don’t, you’ve given them information that may help them to change later.”

Overall, her message is a positive one.

“Remain hopeful. Vet school is hard and stressful, but it gets better. It doesn’t matter if you aren’t sure yet how you fit in the veterinary profession. There are so many options and opportunities.

“Create your own success. Success will look different for each of you, and that’s OK.

“People who have a lot of uncertainty often end up with the most job satisfaction.”

When asked about her own job satisfaction, Dr. Johnson-Walker has this to say:

“I feel job satisfaction, especially when I see former students out there doing it and know that I played a small part in their success.

“And especially when they remember some epidemiology.”

![[Dr. Yvette Johnson-Walker with chickens]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/johnson-walker-feature.jpg)