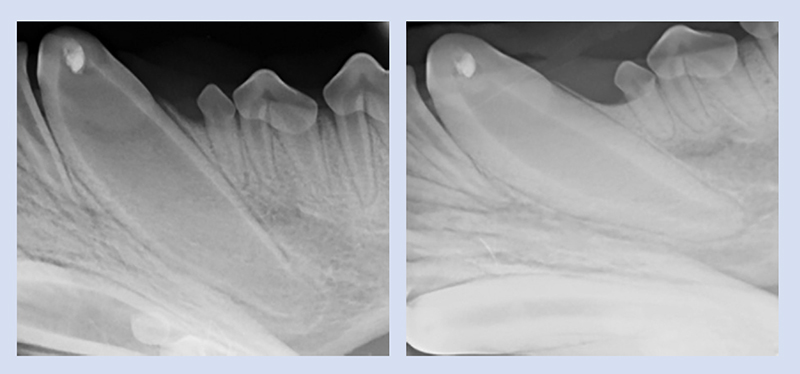

Above: The fracture site on the left maxillary 4th premolar of this 5-year-old German Shepherd was obscured by the fractured-off slab that was still connected to the attached gingiva.

Above: In this 5-year-old mixed-breed dog, ultrasonically scaling calculus from the right maxillary 4th premolar uncovered pulp exposure from a slab fracture that extended under the gingiva.

Your patient has fractured a tooth—now what? There may be multiple treatment options, depending on the situation.

Situation 1: No Exposed Pulp

First, assess if the pulp has been exposed. If not, then treatment may not be needed. If an uncomplicated (no pulp exposure) fracture happened recently, especially if the patient is only a couple years old with relatively wide pulp cavities, then sealing exposed dentin tubules with a composite can reduce or eliminate sensitivity.

A tooth fractured without pulp exposure months or years before may not need sealing, although it is not wrong. In all cases, a dental radiograph should rule out endodontic disease, which can result even from a concussive force that does not cause crown fracture or pulp exposure.

Situation 2: Exposed Pulp

ALL teeth fractured with pulp exposure or with any signs of endodontic disease on dental radiographs (wide pulp canal, periapical or apical lysis) need treatment. If the pulp is bleeding, then it is exposed and contaminated. If much of the crown is gone, then almost certainly the pulp has been exposed, even if it is no longer bleeding.

In some chronically fractured teeth, black, brown, or purulent exudate is apparent at the fracture site. A mucosal or cutaneous fistulous draining tract or facial swelling associated with a tooth suggests endodontic disease and warrants further investigation.

Confirming pulp exposure in the awake patient may be difficult, especially if the fracture timing is unknown. If, with the patient under heavy sedation or general anesthesia, a dental explorer can pass into the pulp cavity, then pulp exposure is confirmed.

Dental radiographs alone are not reliable to confirm pulp exposure. Ultrasonic scaling can reveal a pulp exposure site hidden by calculus accumulation.

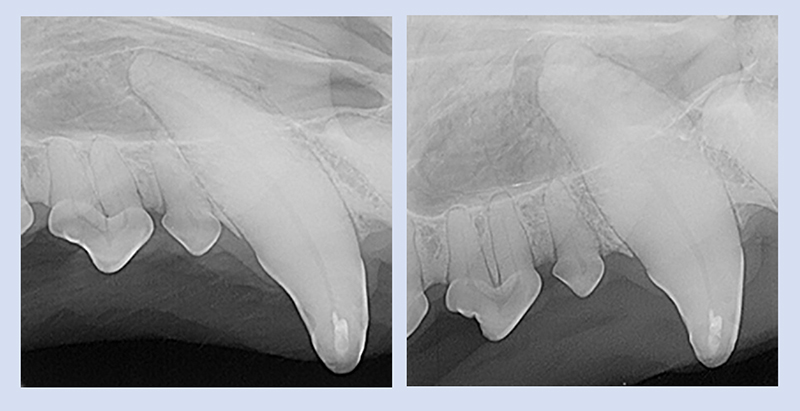

Left: The fractured left mandibular canine in this 7-month-old mixed-breed dog was treated with vital pulp therapy. The wide pulp canal and open apex are appropriate for the age of the dog. There is NO periapical lysis.

Right: The 6-month recheck shows appropriately thickened dentin walls, a closed apex, and a dentin bridge under the radiodense pulp dressing. There is still NO periapical lysis. This tooth is vital and has continued to mature. The procedure was successful.

Right: The 6-month recheck shows no change to the dentin walls, and there is now periapical lysis: the procedure was NOT successful. The same measure may also be used to evaluate the success of root canal treatment.

Treatment Options

Once pulp exposure or endodontic disease is confirmed, treatment may be performed. Regardless of when or how the pulp exposure happened, extraction is never wrong. The problem is eliminated. After complete healing there is almost never a need to re-evaluate the site.

Sometimes a treatment goal is preservation of tooth function or structure, such as with a police dog or with a young, energetic dog who will not tolerate activity restrictions following tooth extraction. In these cases, a root canal may be performed. In a root canal the entire pulp is removed, the canals are filled with a bioinert, biocompatible material that seals the apices and dentin tubules, and the crown is sealed with a composite material. This stops the translocation of bacteria from the mouth to deeper within the body, although the tooth will be non-vital and unable to become stronger by producing thicker dentin.

Under specific circumstances, vital pulpotomy with direct pulp capping and restoration may be appropriate. In a vital pulpotomy only the contaminated pulp (up to 5 to 7 mm) is removed, a dressing is applied atop the remaining pulp, and the tooth is sealed. The goal is to keep the tooth alive to thicken its dentin layer and become stronger and, in immature teeth, to allow the apex to close. This procedure has the best prognosis for teeth fractured within 48 hours of treatment, under relatively uncontaminated conditions.

With any type of endodontic procedure, radiographic re-evaluation of the tooth in 4 to 6 months after treatment and then annually thereafter is recommended, to monitor for continued success. With a successful root canal, a periapical lesion has resolved or a new one has not formed at rechecks. With successful vital pulp therapy, the tooth has continued to mature and develop thicker dentin walls, a dentin bridge under the pulp dressing may be apparent, and no periapical lysis has developed.

If you or your client would like to discuss treatment options for a fractured tooth, please contact the Dentistry Service at 217-333-5859.

Selected References

Clarke DE. Vital pulp therapy for complicated crown fracture of permanent canine teeth in dogs: a three-year retrospective study. J Vet Dent. 2001 Sep;18(3):117-21. doi: 10.1177/089875640101800301. PMID: 11968903.

DeBowes LJ. Simple and surgical exodontia. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2005 Jul;35(4):963-84, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2005.03.004. PMID: 15979521.

Harrán-Ponce E, Holland R, Barreiro-Lois A, López-Beceiro AM, Pereira-Espinel JL. Consequences of crown fractures with pulpal exposure: histopathological evaluation in dogs. Dent Traumatol. 2002 Aug;18(4):196205. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-9657.2002.00075.x. PMID: 12442829.

Kovacević M, Tamarut T, Jonjić N, Braut A, Kovacević M. The transition from pulpitis to periapical periodontitis in dogs’ teeth. Aust Endod J. 2008 Apr;34(1):12-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4477.2008.00120.x. PMID: 18352898.

Kuntsi-Vaattovaara H, Verstraete FJ, Kass PH. Results of root canal treatment in dogs: 127 cases (1995-2000). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002 Mar 15;220(6):775-80. doi: 10.2460/javma.2002.220.775. PMID: 11924577.

By: Dr Amy Somrak, DVM, MBA, DAVDC