Hands-on … Your Own Cat?

Editor’s note: The University of Illinois veterinary curriculum is unusual in devoting eight weeks in the first year and seven weeks in the second year to clinical rotations. Illinois veterinary students also enter their “clinical year” midway through the spring semester of their third year. Then they wrap up their studies with a six-week professional development period. In all, students have more than 20 weeks more time in clinics than at other veterinary schools. As with many things over the past year, the curriculum had to be re-imagined to meet pandemic safety measures.

![[Mackenzie and Florence, her cat]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/sb-mackenzie-cat-240x300.jpg)

To learn a little more about the structure of clinicals in a non-pandemic year, I consulted with very helpful second-, third-, and fourth-year students. According to them, typical first-year clinical rotations consist of “core rotations” and specialized rotations. Each rotation lasts one week, for a total of eight weeks.

Core rotations teach students basic technical skills such as suturing, drawing blood, and performing ultrasounds. In specialized rotations, first-year students work with fourth-year students who are caring for patients in the Veterinary Teaching Hospital. For example, students might assist in such service areas as equine medicine, ophthalmology, and emergency medicine.

Colloquium is also held three mornings a week before students set out for their rotations. Colloquium covers less hands-on (but very important!) information such as career path options, doctor-client communication, and financial planning.

Clinical Rotations During COVID

My clinical rotations this year covered the same educational material, but in different formats. The first five weeks of the term was our true rotation period. Videos that students could watch at home replaced many in-person demonstrations. While first-years still executed these skills in person on campus, online tutorials reduced foot traffic and room occupancy to comply with COVID protocols.

Specialized rotations also had to be modified because of reduced capacity at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital. Instructors modified and recombined elements from these rotations so that they could occur outside the hospital.

Finally, all first-year students rotated through the same five clinical weeks (instead of eight with varying specialized rotations), and all colloquium occurred during the last two weeks of term in an entirely online format.

‘Light at the End of the Tunnel’

While it was certainly disappointing not to have more experience in the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, I still learned a lot during my rotations. My favorite week was probably equine medicine. I hadn’t really spent much time around horses, so it was fascinating to learn what went into their care and treatment. Besides, I have never turned down the opportunity to pet any animal; horses are no exception.

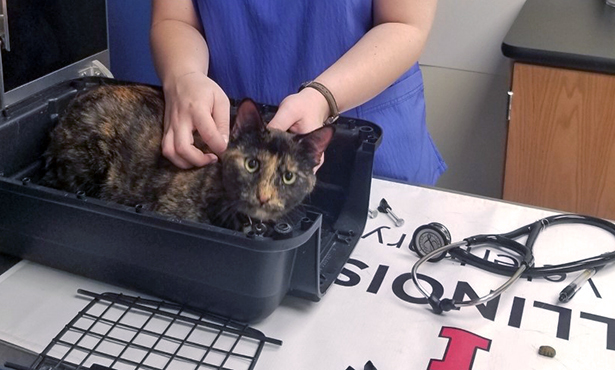

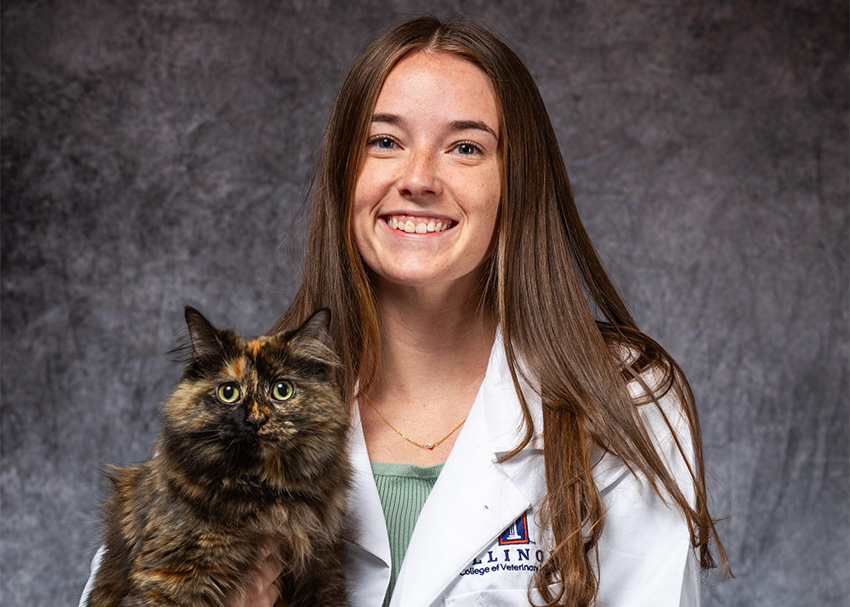

Another memorable rotation day was when students brought their pets to campus to practice physical exams. My cat, Florence, was a skeptical but mostly cooperative patient. I struggled most with my surgical skills rotation, but with the help of faculty and a lot of practice I eventually figured out how to improve my suturing.

I also enjoyed hearing from our guest speakers in colloquium. They were extremely generous with their time and advice on how to navigate various avenues of life as a veterinarian.

However, the absolute best part of rotations was seeing the light at the end of the tunnel—that the hours and days and weeks I spend studying are slowly but surely getting me where I need to be. This spring semester I’ve returned to the classroom, but I’m already looking forward to seeing how I’ll improve in my next—hopefully normal—rotations next year.

By Mackenzie Wells, Class of 2024