The veterinary curriculum is demanding, so when the spring semester draws to a close, many students are more than ready to leave academia behind and dive into clinical work or time off.

But at Illinois and elsewhere, some students stay on for a different kind of learning.

The Summer Research Training Program (SRTP), funded in part by the National Institutes of Health and Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program, provides an opportunity for future veterinarians to experience the world of research. Students are matched with faculty mentors based on the student’s statement of interests and the availability of research projects.

The “results” at the end of this 10-week program are only partially captured in the research findings: the students make important discoveries about themselves, sometimes uncovering or confirming an interest in pursuing a research career.

Collected here are just some of the experiences and discoveries that occurred in the summer of 2018.

Illinois Summer Research Training Program by the Numbers

• 16 years that the program has been offered at Illinois

• 10 weeks, from May 21 to July 27

• 40 hours (minimum) per week working on research

• 19 Illinois veterinary student participants in 2018 (not including Illinois students who participated in summer research programs hosted by other institutions) Read their abstracts.

• 8 weekly group seminars to learn about research careers and scientific writing

• 7 research training modules completed online, e.g., about laboratory safety and the use of animals and human subjects in research

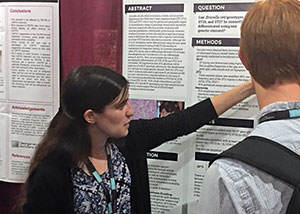

• 2 poster presentations: one for practice at Illinois, one at the National Veterinary Scholars Symposium, which was held at Texas A&M University in 2018

On a Different Timeline: Michael Brooks

![[Michael Brooks]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/res-srtp-brooks2.jpg) Michael Brooks arrived at a veterinary career decision a bit later than the typical student. He attended graduate school in Florida, worked as a field biologist in the southeast, and also worked as an environmental scientist in the Chicago area for a few years before deciding to become a veterinarian.

Michael Brooks arrived at a veterinary career decision a bit later than the typical student. He attended graduate school in Florida, worked as a field biologist in the southeast, and also worked as an environmental scientist in the Chicago area for a few years before deciding to become a veterinarian.

“Being a second-career student was an adjustment, but I think the work experience helped me, especially with the summer research program,” says Brooks. “This program was very useful: I learned to manage my time, to set goals for myself, and to perform a lot of techniques that will be helpful in my future career as a specialist clinician. The ‘soft’ skills of communication and planning have probably been the most important.”

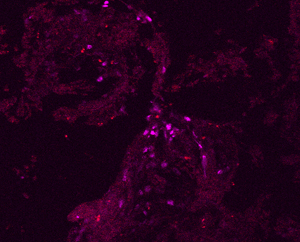

Brooks was paired with mentor Dr. Keith Jarosinski, whose research focuses on identifying viral proteins that could be targeted by drugs or vaccines against herpesviruses. In particular, Brooks worked with a recombinant Marek’s disease virus, which is a herpesvirus that infects chickens.

“We experimentally infected chickens with the virus, collected tissues, and analyzed the tissues to see if the virus expressed certain antigens,” says Brooks. “We also collected tumor cells for a later reactivation study to see if this recombinant virus can separate reactivating cells from transformed/lytic cells.”

“Michael is a talented student who works very well with others, but also was tremendously good independently,” says Dr. Jarosinski. “He generated ex vivo T-cell lines, performed immunofluorescence assays, and performed flow cytometry. He also has a great analytical mind to solve problems.”

Brooks’s advice for other students considering the summer research program is to understand that they may not finish their project or get an expected result, but that is acceptable in the context of the program.

“This research experience has helped me understand the timeline of research,” says Brooks.

Dr. Jarosinski adds: “Take the highs and lows, failures and successes, and build upon them and learn. Failed experiments still provide information that can be used in the future.”

Marine Mammal Research Thrives, Far from the Ocean—and Campus: Allison Dianis

Third-year student Allison Dianis scored a first. Paired with Dr. Karen Terio, chief of the college’s Brookfield, Ill.-based Zoological Pathology Program, Dianis was the first to participate in the Illinois Summer Research Training Program entirely remotely. She attended all the lectures via videoconferencing, traveling to campus only for the visit from the Purdue University summer researchers, for the mentor-student meal, and for the poster session.

Third-year student Allison Dianis scored a first. Paired with Dr. Karen Terio, chief of the college’s Brookfield, Ill.-based Zoological Pathology Program, Dianis was the first to participate in the Illinois Summer Research Training Program entirely remotely. She attended all the lectures via videoconferencing, traveling to campus only for the visit from the Purdue University summer researchers, for the mentor-student meal, and for the poster session.

“We were excited to take Allison Dianis on because she had some prior experience with PCR and prepping samples for sequencing, but had not previously completed the sequence analysis,” says Dr. Terio. “This allowed us to spend time talking about study design, the specific problem we were investigating, and focus on data analysis.”

The research was part of an ongoing project on Brucella ceti infections in wild cetaceans such as dolphins and whales. B. ceti is associated with a host of problems in cetaceans, including abortion, meningitis, and arthritis and can be a factor in stranding. But some forms of B. ceti cause disease in human beings, so people working with stranded marine mammals need to be able to quickly evaluate their risk of exposure to this bacterial strain.

Dianis’s project compared the current standard for identifying strains of B. ceti, which is extremely time-consuming, against a single rapid test that has been developed for other forms of Brucella. She tested 52 samples of B. ceti that had been isolated from cetacean tissues on necropsy using both techniques, and the results indicated that the single test may distinguish among the strains.

“For this project, Allison completed a lot of sequencing and comparing strain typing techniques,” says Dr. Terio. “She was meticulous and very organized, which are excellent skills for any scientist. For us, it was a great experience, and we got some good science done!”

Dr. Terio points out that the summer research program will help students realize that science is often incremental.

“The elusive cure for an intractable disease is unlikely to be found in a two-month summer program, but the experience and skills that they gain can provide the foundation for a career as a veterinary scientist. Even if they decide that research is not for them, they will come away with a greater appreciation for what goes into every discovery, however large or small.”

One Step on the Pathway to Preventing Parasitic Infection: Brina Gartlan

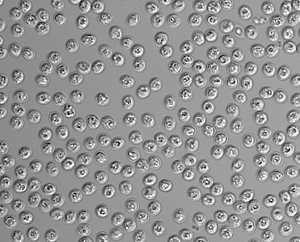

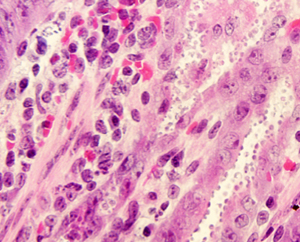

The laboratory of Dr. Sumiti Vinayak studies biology of the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. Cryptosporidiosis is the second leading cause of life-threatening diarrhea in young children and an opportunistic pathogen that afflicts immunocompromised patients. C. parvumis an important veterinary pathogen that causes diarrhea in young farm animals, especially calves.

The laboratory of Dr. Sumiti Vinayak studies biology of the protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. Cryptosporidiosis is the second leading cause of life-threatening diarrhea in young children and an opportunistic pathogen that afflicts immunocompromised patients. C. parvumis an important veterinary pathogen that causes diarrhea in young farm animals, especially calves.

Finding a way to treat or prevent animal and human cryptosporidiosis has been hampered because the organism is difficult to maintain and study in the laboratory, there are poor animal models, and molecular genetic tools are lacking. Then, in 2015, Dr. Vinayak built a powerful system that, for the first time, enabled researchers to genetically manipulate C. parvum. She went on to develop a robust in vivo animal model system for testing the efficacy of anti-cryptosporidial compounds.

(Both these findings occurred while she was at the Center for Tropical and Emerging Global Diseases at the University of Georgia—and both were published in Nature.)

Dr. Vinayak joined the Illinois faculty in 2017, and this was her first year serving as a mentor in the SRTP. She was paired with Brina Gartlan, a second-year student, with a background in molecular biology and an interest in surgery.

Gartlan’s project involved using a genome-editing tool (CRISPR/Cas9) and an immunocompromised mouse model to create a transgenic knockout strain to show that calcium dependent protein kinase-1 is essential for growth in C. parvum. Additional ongoing studies are aimed at investigating the function of this protein in C. parvum.

“Brina is a fantastic student and a quick learner. She was very enthusiastic and motivated about her project since it involved animals (mice), infection experiments, and histology,” says Dr. Vinayak.

Gartlan said her summer experience was helpful because her mentor was willing to teach and the weekly seminars helped her write a manuscript, abstract, and poster. Says Gartlan, “These are all essential parts of research that haven’t been available to me before.”

Gartlan also credits Dr. Lois Hoyer, associate dean for research and director of the summer program, for a very positive match process, “and she has been incredible when it comes to editing abstracts or reviewing posters.”

Dr. Vinayak’s advice to future students is “to explore ongoing research programs and see what best fits your interests, and long-term goals. To get the most learning experience, meet with your mentor and try to read relevant papers before you start the program.”

Putting Health on the Map: Bennett Lamczyk

What’s a geographer doing on the faculty of the veterinary college? Dr. Marilyn O’Hara Ruiz answers this question succinctly in her research biography: She “applies the concepts and technique from spatial science to epidemiology and the problems of disease transmission in an ecological setting.”

What’s a geographer doing on the faculty of the veterinary college? Dr. Marilyn O’Hara Ruiz answers this question succinctly in her research biography: She “applies the concepts and technique from spatial science to epidemiology and the problems of disease transmission in an ecological setting.”

In the nearly 20 years since the mosquito-borne West Nile Virus (WNV) was introduced into the U.S., Dr. Ruiz has been at the forefront of figuring out which factors contribute to WNV infection rates. Her team developed a model that pulls data from lots of sources—from the presence of vegetation in the area to the age, income, and race of the people in the neighborhood to the local mosquito abatement practices—to predict human cases in the Chicago, Ill., area.

This summer, second-year veterinary student Bennett Lamczyk tackled a research project that sought to explain discrepancies between the WNV model’s predictions and the actual rate of human infection in selected areas covered by the model. He conducted surveys to find out how much outdoor activity residents in those locations engaged in during the peak-mosquito evening hours.

Results from his work may allow researchers to further increase the accuracy of the prediction model and improve public health in the region.

“Being able to work in the field of epidemiology was a life experience that has helped shape my future goals,” says Lamczyk. “The knowledge gained in conducting an experiment, analysis, and statistics surpassed my goals of obtaining a basic background in the research field. Not only did I receive training in research and the field of epidemiology, but I also now have more connections at the University of Illinois campus.”

Dr. Ruiz also served as mentor to a summer research student, Melanie Repella, who worked on a tick-borne disease study. Dr. Ruiz says her lab benefited from hosting the students: “The students make significant contributions in areas that we might not have otherwise had the human power to address. Plus, the graduate students in my lab helped mentor the summer students, which is very beneficial to both groups.”

One Summer, Two Research Projects: Ivana Levy

Second-year student Ivana Levy managed to accomplish two separate projects this summer.

Second-year student Ivana Levy managed to accomplish two separate projects this summer.

“One of my projects was a prospective study while the other was retrospective,” says Levy, “so it was a unique and informative experience to work on such completely different projects.”

Paired with Dr. Krista Keller, a clinical faculty member boarded in zoological medicine, Levy investigated methods to measure core body temperatures in guinea pigs and also reviewed data from the Wildlife Medical Clinic to determine prognostic indicators for survival in young or orphaned eastern grey squirrels.

“I worked extremely well with my mentor,” says Levy. “I was paired with someone who is communicative, open to novel ideas, and extremely helpful and encouraging. Plus, I am interested in pursuing a career in her field of research.”

The guinea pig study addresses a clinical problem faced by veterinary caregivers. Body temperature is an important piece of patient information, but having a temperature taken rectally can be stressful for small species like guinea pigs. Levy compared temperatures measured in the armpit and groin area with those taken rectally in guinea pigs. Though the various readings are not interchangeable, they developed a formula clinicians can use to calculate the core body temperature using a less-invasive measures. For example, rectal temperature is equal to armpit temperature plus 0.44 Celsius degrees.

Additional investigation is planned to assess the relative temperature measurements in animals suffering from disease.

“I hope that this study can seed into a larger prospective study to evaluate whether body temperature on admission can be a predictor of survival in guinea pigs,” says Dr. Keller. “As guinea pigs are common companion animals, understanding this information can help veterinarians make informed decisions about care for sick guinea pigs.”

In her other project, Levy found that squirrels who presented with any type of body system abnormality, neurologic disease, or respiratory disease or that arrived in the second half of the year were more likely to be non-survivors.

“Wildlife clinics have limited resources,” she notes, “and this information can help clinicians identify patients that need more aggressive treatment or novel therapeutic agents. It may also improve overall efficiency in wildlife clinics by reducing the misuse of limited clinical resources.”

“This was my first year as a mentor in the program, and I am very impressed with the amount of training, exposure, and mentorship that the students receive not only from their primary mentor but from the program itself,” says Dr. Keller. “It is an opportunity that I wish I had taken advantage of all those years ago when I was a student!”

International Summer Research Experience: Zoe Morris

Zoe Morris, a third-year veterinary student, found a research opportunity through the Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program that, each year, selects a small number of students to participate in a research opportunity at a European veterinary school. She spent the summer at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, analyzing data pertaining to antimicrobial resistance in a swine slaughterhouse.

Zoe Morris, a third-year veterinary student, found a research opportunity through the Boehringer Ingelheim Veterinary Scholars Program that, each year, selects a small number of students to participate in a research opportunity at a European veterinary school. She spent the summer at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, analyzing data pertaining to antimicrobial resistance in a swine slaughterhouse.

Her work comprised a small part of the large multi-national European Ecology from Farm to Fork of Microbial Drug Resistance and Transmission project. Her research adviser, Dr. Lidwien Smit, works at the Institute for Risk Assessment Science in Utrecht, with a focus on environmental epidemiology.

“This research will be beneficial in my career as it allowed me a more analytical component and less of a clinical aspect, which I have previously had in my other research experience,” says Morris. “I made great connections and was able to experience some of the differences in research between Europe and the United States.”

Morris was involved in meetings regarding all the data that had been collected and is being analyzed. She expects the project to be very useful in the future as the issue of antimicrobial resistance grows to be a worldwide concern.

“The experience was very useful,” says Morris. “I learned how to use Statistical Analysis System for data analysis and the different ways to examine the large amount of data that I was given.

“I would recommend the program to anyone and everyone. It was an amazing experience where I met many incredible people.”

Evaluation of Training Program Counts as Research: Danielle Schneider

Danielle Schneider’s project proves that “research” does not always equal standing at a lab bench in a basement all summer.

Danielle Schneider’s project proves that “research” does not always equal standing at a lab bench in a basement all summer.

This third-year student was paired with Dr. Maureen McMichael on a project that evaluated a training program for first responders such as emergency medical technicians, paramedics, police officers, and firefighters.

On May 14, Dr. McMichael and other college personnel delivered an afternoon of training to approximately 60 police K9 handlers. The first responders rotated through 14 stations, learning such skills as how to administer an opioid antidote, naloxone, to an exposed dog; how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a dog; and how to recognize and provide the first line of care for conditions such as bloat, heatstroke, bone fracture, and poisoning.

Schneider assisted in the training and also surveyed a subset of the handlers before and after the hands-on training. Results showed that the handlers felt more comfortable with treating injuries as a result of the training.

“This project gave me the opportunity to see how my first passion, veterinary medicine, and my second passion, working dogs, could be merged together,” says Schneider.

The research training program’s instruction on manuscript writing particularly paid off for Schneider, who, with Dr. McMichael, wrote up her results for publication and will be first author on a paper.

“I absolutely loved my mentor,” says Schneider. “She supported me throughout the research process, and I have truly been inspired to continue the work we have done.”

Dr. McMichael says, “Danielle is meticulous, a hard worker, a fantastic writer, and a wonderful person.”

The faculty member also wants students to recognize that “clinical research is done in the field, in the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, or just about anywhere.”

On Track for a Research Career: Allison Tomasino

Second-year student Allison Tomasino already knew she wanted to be a researcher when she started her veterinary studies. Her summer research experience confirmed this goal.

Second-year student Allison Tomasino already knew she wanted to be a researcher when she started her veterinary studies. Her summer research experience confirmed this goal.

“It has shown me that I still want to continue on a research track in the future and made me feel confident in the route I am taking to get there.”

Tomasino previously worked at the National Institutes of Health, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, and the US Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense, starting as an animal caretaker/technician then moving to a position as a research assistant for the Regenerative Medicine Department of the Operational Undersea Medicine Directorate at the Naval Medical Research Center in Silver Spring, Md. In all, she spent four years in the research field.

“It’s hard to describe the rewarding feeling of having been a part of something that can change animal and human health,” says Tomasino. “It’s the reason why I want to end up back in biomedical research post-graduation as a laboratory animal veterinarian.”

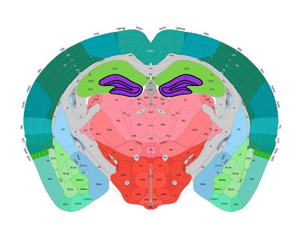

Tomasino worked with Dr. Justin Rhodes, a professor of psychology located at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. Dr. Rhodes’s laboratory had discovered that a diet high in cocoa flavanols prevents age-associated declines in blood perfusion throughout the brain in aged mice. Tomasino’s project involved analyzing sections of mouse brains from the experimental and control groups in the earlier study to see if the mechanism for these beneficial effects was due to higher levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), the enzyme responsible for nitric oxide production.

“This program was useful to keep my hands-on research skills fresh, but also let me learn new aspects of research,” says Tomasino. “I had never previously written an abstract or made a poster before. This program allowed me to get that experience and feel more comfortable about them in my future!”

She highly recommends the program to other students, especially if they are interested in research. She even advises students on the fence about research to apply because the program gives a great introduction to what research is all about.

Cancer Research Career Begins Now: Christine Tran Hoang

“I knew that I wanted to do research in oncology before starting veterinary school, and I was able to pursue that interest because I was paired with Dr. Fan,” says third-year Christine Tran Hoang.

“I knew that I wanted to do research in oncology before starting veterinary school, and I was able to pursue that interest because I was paired with Dr. Fan,” says third-year Christine Tran Hoang.

Her summer research project concerned the possible anticancer effects of a drug called simvastatin on canine osteosarcoma cells. Osteosarcoma is the most common primary bone tumor in dogs, and almost all dogs that have this cancer will develop lung metastases.

In human cancer studies, simvastatin decreases tumor progression and metastasis, possibly by stimulating the shedding of a receptor called CD44. Tran Hoang and Dr. Tim Fan hypothesized that treatment with simvastatin will decrease expression of CD44 receptors on the cancer cell membrane. Her results seem to support that idea, and further studies will continue to explore the potential value of simvastatin for treating canine osteosarcoma.

Tran Hoang says the experience was invaluable to her because the research experience and the possible clinical application is directly related to what she wants to do in her future career.

“I am interested in specializing in oncology, and someday helping to run the clinical trials that would make new cancer treatments available for our patients,” says Tran Hoang. “The opportunity to test out a possible future cancer therapeutic in the lab is exactly what I want to be working on.”

The program helped to develop her skills as a clinician-scientist. She was able to enhance her existing benchtop skills while learning new lab techniques. In addition, she had the freedom to plan her own experiments, which gave her the confidence to become the expert in the topic and develop vital skills such as critical thinking, planning, and troubleshooting abilities.

“I have had the opportunity to mentor over a dozen professional veterinary students over the past 10 years, and I feel very fortunate this year to be paired with Christine Tran Hoang,” says Dr. Fan. “Christine embodies all of the elements of a promising young researcher: she is enthusiastic, motivated, and independent, with an overall positive attitude for research successes and failures.”

Entrée Into Big Research Field: Sarah Zalar

Sarah Zalar, a second-year student, spent her summer at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Md., through the Summer Internship Program in Biomedical Research for Veterinary Medical Students.

“I worked on noroviruses, a leading cause of gastroenteritis worldwide,” says Zalar. “There are still many challenges facing gastrointestinal research. My work focused on developing successful culture systems to better study the virus and its tropism using a 3D organoid culture system. Additionally, I worked on sequencing and cloning the viral polymerase from a specific recombinant strain of the virus that is newly emerging, the GII.P16 variant.”

Dr. Kim Green, the chief of the Caliciviruses Section in the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, was Zalar’s adviser.

“I was unsure how many opportunities there were for veterinary research and thought that it was a very small field, when it is actually quite large,” says Zalar. “The NIH connected me with veterinary scientists at zoos, other federal agencies, and in academia.”

Zalar says the best part of her research experience was the ability to work at a leading research facility and an amazing lab.

“This program was very useful to me,” says Zalar. “I attended two conferences and was able to network with various veterinary scientists as well as successful researchers.

“I would highly recommend this program to any students remotely interested in research, lab animal medicine, pathology, or really anything else. I was even able to meet the surgical chief here, so veterinary students interested in a surgical residency could learn a lot, as they do surgery on pigs, deer, dogs, cats, primates, really anything! The NIH has been wonderful for matching you with your interests and accommodating if you are not happy.”

—Da Yeon Eom

Featured photos of students provided by Betsy Innes and Lois Hoyer.

![[Summer Research Training Program - Tran Hoag]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/res-2018-srtp.jpg)