When Jan Jannusch noticed that her 13-year-old cat, BJ, was having trouble breathing, she took him to see a veterinarian. The cause of BJ’s problem turned out to be “idiopathic chylothorax,” a disease so rare that many veterinarians won’t encounter a single case of it in their entire career.

That’s why BJ’s doctor recommended seeing the experts at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital.

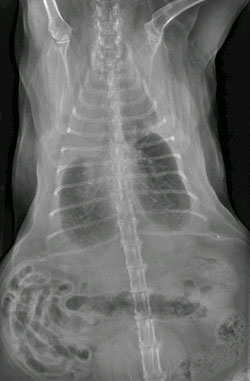

Idiopathic chylothorax causes fluid to accumulate in the space around the lungs. Normally there is a small amount of clear fluid surrounding the lungs to ensure that the lungs don’t adhere to the chest wall. But in chylothorax, a milky fluid, called chyle, drains from the intestinal tract and builds up in the space around the lungs instead of being routed through a duct system into the bloodstream to be cleared from the body.

BJ’s condition was “idiopathic,” meaning that doctors ruled out heart disease and other possible causes for the accumulation of fluid, so the cause of the disease was unknown. Idiopathic chylothorax in cats generally carries a very poor prognosis.

BJ couldn’t breathe because the accumulated fluid prevented his lungs from expanding fully.

At first the veterinarians at Illinois recommended a dietary approach. BJ was put on a low-fat diet and prescribed rutin, a natural compound found in some fruits that is thought to help reduce the fat content of the chyle. The treatment appeared to work for a while, but Jannusch noticed that BJ’s condition worsened again after a couple of months.

“BJ showed up at my door as a stray several years ago, and he has been with me ever since. Seeing him suffering and struggling to breathe was difficult,” Jannusch said.

Doctors drained nearly half a cup of fluid from BJ’s chest, and just a few days later they had to drain his chest again.

At this point Jannusch met with surgeon Dr. Heidi Phillips to discuss a more aggressive approach to treating BJ. Dr. Phillips recommended surgically closing ducts in the thorax and removing a structure where chyle and lymph fluids collect. These procedures, when performed together, are thought to work by changing the pressure dynamics within the body in such a way that permits the chyle to move directly from the abdomen to the bloodstream without going through the duct system.

The veterinary medical literature contains a few reports of these procedures having some success in dogs, but the procedure had only anecdotally been performed in cats.

Dr. Phillips also advised placing a pleural port, which she described as “basically an internal chest tube, wholly under the skin and sterile, through which a primary veterinarian or owner could more easily drain fluid from the chest.”

“Having this drain in place is helpful while waiting for chylothorax to resolve, or in the event the surgery is not successful,” Dr. Phillips said.

The surgery went well; unfortunately, complications that followed involved an upper respiratory infection and two extra weeks in the hospital for BJ.

The doctors who worked with BJ took the best possible care of him. A geriatric cat when the surgery took place, he was already in a fragile condition. Though his recovery was slow, BJ returned to being the thriving cat he was before.

“I can unequivocally recommend the U of I vet clinic, especially if you have an animal with an unusual or difficult condition. We are now almost three months post surgery and [BJ] is currently symptom free! I will be forever grateful to everyone at the clinic who was involved with BJ during his lengthy stay,” Jannusch said.

—Emily Luce