Turtles play a role in environmental health

![[Marta Kelly, Lauren Mumm, John Winter]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-turtles-three.jpg)

Mumm, from Rogers, Minn., and Winter, from Fort Myers, Fla., braved “swamp foot” (infected toes), deceptively deep marshes, and turtle pee (which managed to baptize everything from their gear to their waders and even their phone) to help evaluate the health status and disease threats of this declining species. And every week of the summer, they wrote a blog to showcase their adventures.

Below is their blog post from June 5, entitled “Meet the Turtles.” Read all their posts at: vetmed.illinois.edu/wel/.

Blanding’s Turtle: Habitat and Diet

The Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) comes from the family Emydidae, which consists of pond turtles such as red-eared sliders and painted turtles. Blanding’s turtles are classified as semi-aquatic turtles, meaning they divide their time between water and the land between wetlands.

![[Marshes in Lake County]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-turtles-panorama.jpg)

![[smiling Blanding's turtle]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-turtles-smile.jpg)

Blanding’s Turtle: Appearance

Unique characteristics of the Blanding’s turtle include its coloration, shape, and of course its signature smile. A Blanding’s turtle has a dark brown/black shell, sometimes with bright yellow spots on the carapace (top shell), providing good camouflage in the more heavily vegetated areas. Its head and legs are also dark, while its chin and throat is a bright, vibrant yellow. Its carapace is more domed than that of the painted turtles with whom it shares ponds, and tends to dome more with age.

A unique feature the Blanding’s turtle is its curved mouth, which is shaped so that edges of the top beak curl upward, endowing these turtles with a deep smile.

Blanding’s Turtle: Survival

Throughout much of its natural range (the Great Lakes region), the Blanding’s turtle is listed as threatened or endangered on the IUCN Red List. (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™, put out by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, is widely recognized as the most comprehensive, objective global approach for evaluating the conservation status of plant and animal species.)

The main causes of population decline include habitat loss and fragmentation from human development, genetic diversity loss due to small population size, small numbers of turtles living to reproductive age, and predators. Human development and ecological imbalance, such as an abundance of beavers, has destroyed or altered areas where Blanding’s turtles live. For example, in Illinois, dwindling numbers of large predators has led to an increase in the beaver population. Beavers make dams, creating deeper ponds with little water flow and pushing out the Blanding’s turtles, which prefer shallower areas.

![[Dr. Matt Allender's motto]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-turtles-ma.jpg)

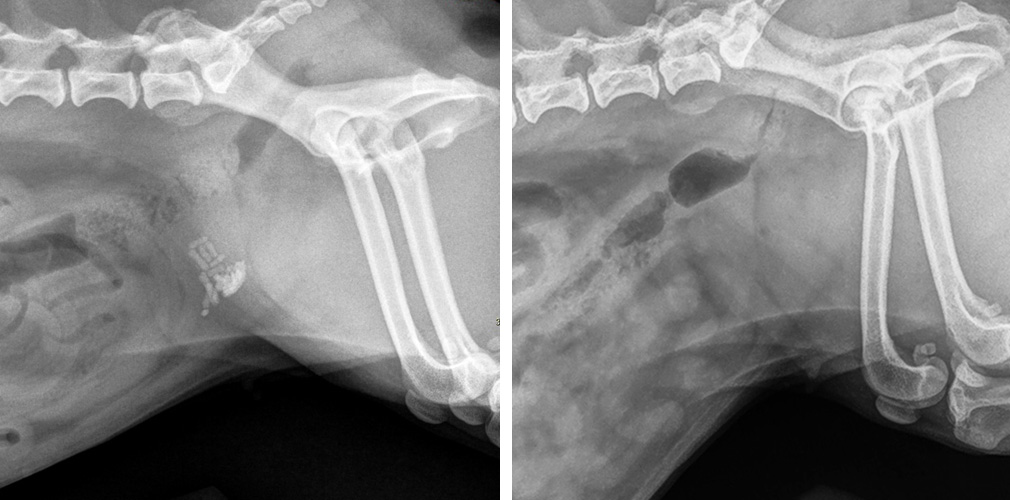

Major predators to turtles in general are raccoons, skunks, crows, and foxes. An abundance of predators negatively affects the survival rate of our Blanding’s turtle friends. Some of the turtles we have encountered this summer have had signs of predator encounters, including what appears to be bites taken from shells or scarred/damaged appendages. Data from the Lake County Forest Preserve show that between 2004 and 2010, less than 8 percent of Blanding’s turtle nests avoided destruction by raccoons or other predators, unless the nests were protected by human intervention.

Blanding’s Turtle: Role in Ecosystem Health

So why care about saving an endangered species? Biodiversity! It is important that we conserve and save native plants and animals to prevent extinction of natural ecosystems. Losing a single species can result in a detrimental domino effect on the rest of the ecosystem in which that species resides.

Most significantly, species loss will affect the natural food chain. Each species contributes to maintaining a healthy equilibrium of all populations and resources that even we humans rely on. Ecosystem equilibrium can prevent invasive species development as well as movement into new habitats, such as predators moving into residential areas. The thought of raccoons and coyotes moving into local neighborhoods is unappealing to many people. Preserving Blanding’s turtles, as well as other threatened and endangered species, is crucial to environmental health and stability.

![[Blanding's turtle]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-turtles-wel.jpg)