Other roles: ensure lifelong comfort and health

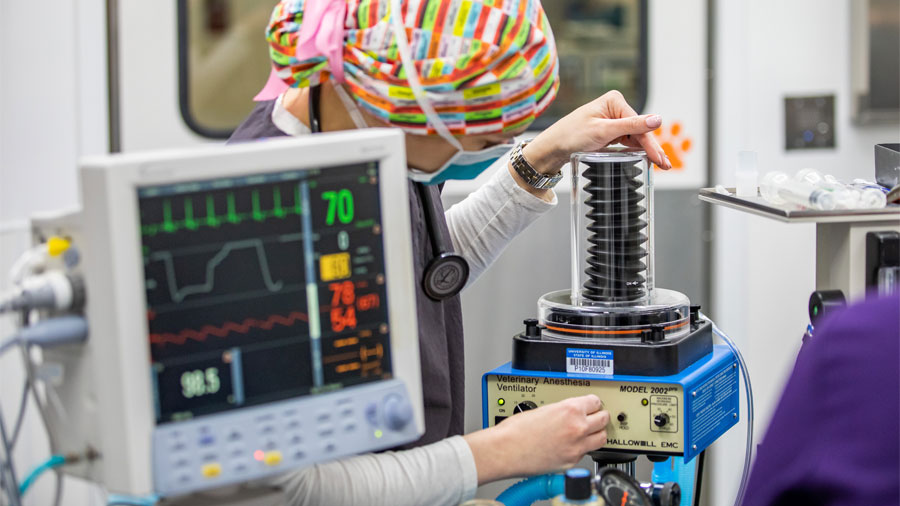

Anesthesia—a controlled state of unconsciousness, almost like induced sleep—is used during a variety of veterinary procedures to ensure that the patient doesn’t feel pain, remains still, and is unaware of what is happening around them.

While all veterinarians are educated to safely anesthetize their patients, some go on to specialize in anesthesiology and most often work at referral specialty hospitals. Dr. Lynelle Graham is one of three board-certified veterinary anesthesiologists at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana. (In the photo above, Dr. Graham poses with her dog, Lulu, in the pre-op room at the hospital.)

Becoming a Veterinary Anesthesiologist

In addition to earning a bachelor’s degree and a four-year Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degree, these specialists complete a one-year internship or equivalent private practice experience followed by a three-year residency program that qualifies them to take the anesthesiology board certification examination. Doctors who have completed this process are noted as “Diplomates of the American College of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia.”

Veterinary anesthesiologists work with a wide variety of animal species, from small and large domestic animals like cats and horses to unusual animals like birds and spiders. Even among species that are routinely anesthetized by general practitioners, some patients may need to be referred to a specialist because of complicating illnesses, a history of not doing well under anesthesia, or other extenuating circumstances.

Dr. Graham explains, “Veterinary anesthesiologists provide support before, during, and after the procedure. We develop individualized plans and can provide a higher level of care for patients who are at increased risk.”

Delivering Anesthesia

Delivering anesthesia is a multi-step process.

“The patient is examined beforehand, and we consult with the primary clinician and the owner about any pertinent anesthetic history so we can develop a plan and decide on appropriate drugs,” says Dr. Graham.

“Animals get an intravenous catheter so medications can be administered easily. Some animals get a premedication to relax them and reduce the need for other drugs. Then they are induced with drugs that go into the blood via the catheter, making them unconscious so that a tube can be passed into the airway. This tube is how we get the gas anesthesia into the lungs to keep the patient asleep.”

Throughout the procedure the patient is closely monitored by the anesthesiologist and specialty trained technicians. The drugs used for veterinary patients are mostly the same ones used in human medicine. Many of the techniques, such as epidurals or dental blocks, are similar to those done in human patients.

As in human medicine, there are risks associated with anesthesia in veterinary practice. Veterinarians work to minimize potential side effects and stressors. They weigh the risks and benefits of an anesthetic procedure before recommending the protocol for their patients.

“After undergoing anesthesia, pets may need a day or two to begin feeling completely like themselves—which you can understand if you have ever had a procedure that required anesthesia,” advises Dr. Graham. “They may be a bit lethargic. If you have any concerns, call your veterinarian and ask.”

Lifelong Comfort of Animal Patients

Veterinary anesthesiologists also support the veterinary team to ensure the lifelong comfort and health of their patients.

“Anesthesia is more than just the science of drugs and inhalants,” says Dr. Graham. “This field encompasses the bigger picture of patient care before, during, and after surgical and diagnostic procedures as well as the management of chronic pain. We are becoming more integrated into everyday practice.”

If you have questions about veterinary anesthesiologists, specialty technicians, or anesthesia, contact your local veterinarian or the anesthesiologists at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital. You can also go to the websites of the American College of Veterinary Anesthesia and Analgesia (www.acvaa.org) and the Academy of Veterinary Technicians in Anesthesia and Analgesia (www.avtaa-vts.org).

By Hannah Beers

![[veterinary anesthesiologists - Lynelle Graham]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-anesthesia-graham.jpg)