Most pet owners think of spaying their female pets to avoid unwanted litters and behaviors. But there’s another, much more urgent reason to spay your dog or cat: to protect her from a potentially life-threatening infection called pyometra.

“Pyometra is an infection of the uterus, commonly a bacterial infection,” explains Dr. Alyssa Baratta-Martin, a primary care veterinarian at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital. “It develops when bacteria ascend from the vagina into the uterus.”

These infections can escalate rapidly, especially when the cervix is closed, trapping pus and bacteria inside the uterus. In fact, there’s a saying in veterinary medicine that captures just how critical early treatment is: “Never let the sun set on a pyometra.”

That’s how fast things can go from manageable to fatal.

Signs of Pyometra

The most common signs of pyometra can be easy to miss at first. They include lethargy, vomiting, lack of appetite, vaginal discharge, and increased thirst and urination.

“Although some of these signs may seem vague, the possibility that they indicate a pyometra increases when they arise a few weeks to months after the pet’s last heat cycle,” says Dr. Baratta-Martin. “Pyometra occurs most often in pets aged 7 years or older.”

However, any intact female can develop pyometra at any point in her life. The risk isn’t limited to senior pets.

Pyometra can escalate quickly, especially in what’s known as a closed pyometra. In this condition, the cervix is sealed and infectious material builds up inside the uterus.

“Risk of uterine rupture, sepsis, and death is even greater in these cases,” Dr Baratta-Martin warns. That’s why early recognition and urgent treatment are so critical.

Treatment for Pyometra

The preferred treatment for pyometra is straightforward: spay surgery–specifically, an ovariohysterectomy to remove the infected uterus and ovaries.

“Surgical removal of the uterus almost completely eliminates the chance of recurrence,” says Dr. Baratta-Martin. “For a closed pyometra, the surgery should take place within 24 hours of diagnosis.”

A non-surgical alternative uses prostaglandin hormones to induce uterine contractions that expel the infection. That treatment is appropriate only when the pet has an open pyometra and the owners intend to breed her.

“The non-surgical approach can take up to a week to clear the infection,” says Dr. Baratta-Martin, “and does not eliminate the risk of a future pyometra.”

It’s Never Too Late to Spay

Fortunately, the prognosis for pyometra is typically good, especially when diagnosis and treatment happen early in the disease process. If the disease results in the uterus rupturing, the outlook becomes very grave.

“We can prevent pyometra in dogs and cats with a spay procedure that removes both the ovaries—the hormone source—and the uterus—the site of infection,” Dr. Baratta-Martin explains.

She wants to dispel a misconception she hears from pet owners who say their older pet is “too old” to be spayed safely.

“Performing a spay procedure on an older pet is always so much better than performing a spay on an older pet who has a pyometra,” she cautions.

Dr. Baratta-Martin urges pet owners to talk openly with their veterinarian about their pet’s reproductive health and long-term care plan.

“If a pet is not intended for breeding, I recommend spaying all female dogs and cats,” she says.

The bottom line? Pyometra is painful, dangerous, and preventable. If your unspayed pet exhibits signs that could mean pyometra–especially after a heat cycle–don’t wait. Contact your veterinarian before the sun sets.

By Julia Bellefontaine

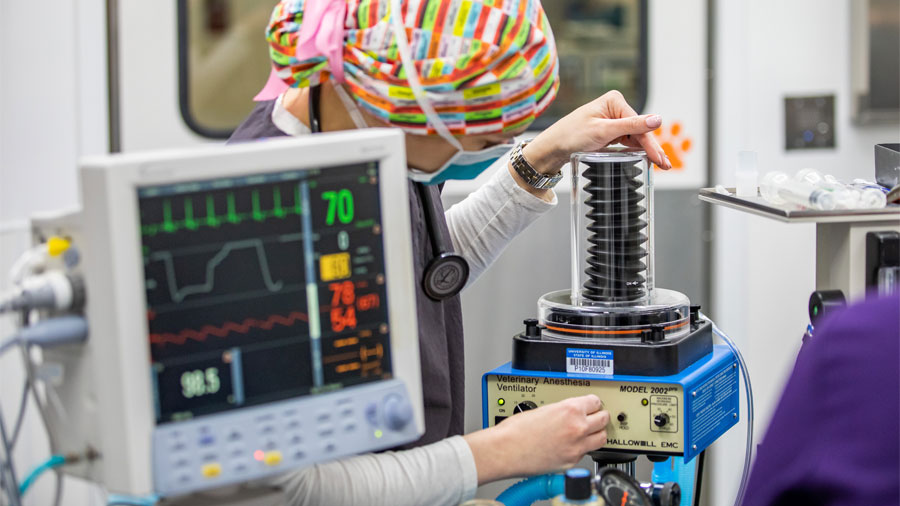

Feature photo by Fred Zwicky shows Illinois veterinary student Hannah Vander Ploeg (left) examining a female dog with Dr. Alyssa Baratta-Martin.