Faster, More Detailed Diagnostic Imaging

On March 31, the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana held a ribbon-cutting ceremony for its new 3T MRI scanner, the only large-bore 3T MRI scanner in the Midwest.

![[mri-horse]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/news-mr-horse-300x180.jpg)

(The tesla, named for the scientist Nikola Tesla, is the unit of measurement used to describe the strength of a magnetic field.)

Magnetic Powers

“While radiographs and computed tomography (CT) use radiation to create images, the MRI uses a magnetic field and radiofrequency pulses,” explains Sue Hartman, the senior imaging specialist at the hospital. Although there is no radiation exposure, safety procedures must be followed due to the high magnetic field. Staff participate in additional screening and training on what is safe to bring into the magnetic field, which is always present. Special MRI-compatible equipment is used.

![[cake in MRI]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-mri-cake-214x300.jpg)

Speed and Clarity

“Having a stronger magnet means that our MRI scanning time is much shorter,” Smith explains. “An individual scan takes between 1 to 6 minutes when it used to take 8 to 12 minutes. This means the total time for an MRI drops from as high as 3½ hours to roughly an hour.”

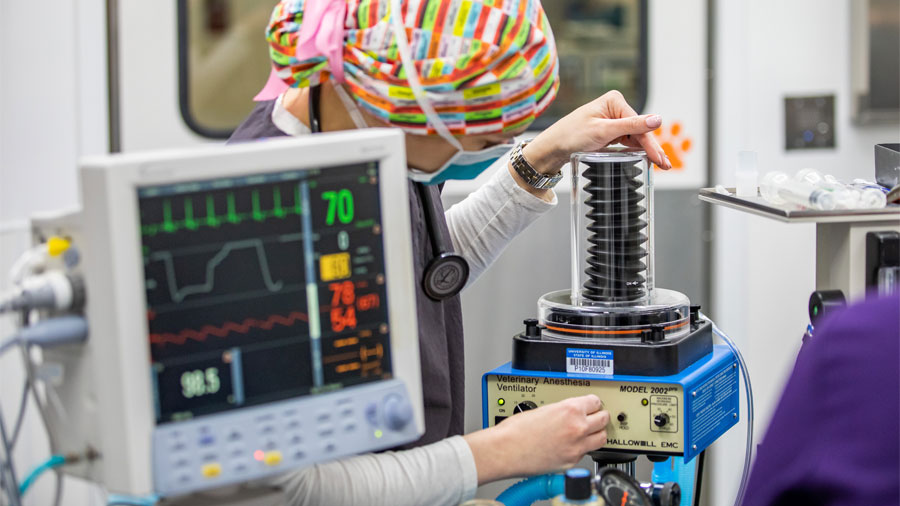

This speed makes the procedure safer for animal patients. Unlike people, animals have to be anesthetized while being imaged. “It’s impossible for our patients to be awake and remain completely still, especially with the loud noises made by the machine while scanning,” Smith says.

In addition to reducing the time under anesthesia, the new MRI generates much more detailed images.

“We are able to have more complexity in the series of scans we generate, and our resulting images are more precise and clear,” Hartman says. “We can also scan individual nerves in higher detail and can create better cardiac images, so this new magnet is greatly enhancing our neurology and cardiology services.”

While most of the patients imaged at the hospital are dogs or cats, the new MRI machine can also scan the head, neck, legs, and feet of large animals, such as horses.

Valuable Diagnostic Data

MRI machines are very expensive, and they are also expensive to maintain. “A costly liquid called cryogens is required to keep the magnetic field functioning at an optimal level,” Hartman says.

![[a Doberman named Lucy benefitted from the new 3T MRI]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-mri-lucy-187x300.jpg)

Hartman says animal owners sometimes get frustrated when they have paid for an MRI scan for their animal and the results are completely normal.

“This doesn’t mean the MRI was a waste of time,” she says. “It means that we are able to rule out all possible causes for the animal’s symptoms that would have shown up on an MRI. When treating an animal, knowing what is not affecting the animal is just as important as knowing what is.”

Opportunities for Research, Cardiology Care, More

Specialists at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital are excited about using the new MRI to advance the practice of veterinary medicine.

“We now have the same MRI capabilities as the University’s Beckman Institute, a world-class imaging research program,” says Dr. Devon Hague, one of two boarded veterinary neurologists at Illinois. “This opens up opportunities to collaborate with biophysicists there to develop new imaging sequences for animal patients.”

Veterinary cardiologist Dr. Ryan Fries has gained cardiac MRI certification at human health organizations in order to pioneer use of the MRI in his field.

“MRI protocols for hearts have never been implemented in veterinary medicine. This is a new way for evaluating cardiac disease in animal patients,” he says. “Once we have established protocols, we will begin clinical trials to explore new standards of veterinary cardiac care.”

By Danielle Engel

Feature photo by L. Brian Stauffer

![[new MRI at Illinois veterinary teaching hospital]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-mri-event.jpg)