The University of Illinois is one of four research institutions that received a Morris Animal Foundation feline research grant in 2017. The Illinois project, led by Drs. Timothy Fan and Alycen Lundberg and co-investigator Prof. Paul Hergenrother, examines a new treatment approach for feline oral squamous cell carcinoma, the most common mouth cancer in cats and one that currently has very limited treatment options.

“Cats diagnosed with oral squamous cell carcinoma typically present with large tumors or advanced disease and therefore live about 2 to 3 months following treatment,” says Dr. Lundberg, a veterinarian who sees patients through the Cancer Care Clinic at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana. She is also pursuing a PhD in the Department of Pathobiology.

Feline oral squamous cell carcinoma is often seen in older cats. Males and females are equally susceptible. Early signs of the disease are similar to signs of bad oral health, such as drooling, having distinctly foul-smelling breath, or wanting to eat but being unable to. There may also be swelling or facial deformities due to tumor growth. The tumor may be visible in the cat’s mouth.

Current Treatment Options Limited

“Oral squamous cell carcinoma is very locally aggressive, but does not have high metastatic potential, which means it’s less likely to spread to other parts of the body,” says Dr. Lundberg. “Surgical removal is rarely an option, unless the cancer is caught very early. Otherwise, radiation and chemotherapy are used most of the time.”

Radiation therapy is used to slow down the tumor growth. It is typically combined with traditional chemotherapy to increase the effectiveness of treatment. However, the success of these treatments is short-lived, and the cancer ultimately progresses.

That is why it is important to find a new and effective treatment for this type of cancer.

New Compound Targets Tumor Cells

The grant received by Drs. Fan and Lundberg will help fund a clinical trial of a new anti-cancer compound developed by Prof. Hergenrother in the Department of Chemistry on the Urbana campus. This compound targets an enzyme, NQ01, that is produced in high numbers by cells found in tumors, especially in oral squamous cell carcinoma tumors.

“The treatment approach is distinct because it targets only cells that express this enzyme, which are the tumor cells,” Dr. Lundberg says, “whereas most traditional chemotherapy treatments attack all rapidly dividing cells, both normal and cancerous.”

The anti-cancer drug, called IB-DNQ, is administered intravenously and has already demonstrated positive results in pilot testing with cats. According to Dr. Lundberg, when the new drug was used in combination with radiation, there was close to a 45 percent decrease in tumor size. Radiation is used to increase the targeted cell enzyme in the tumor, making the treatment more potent and specific.

Reduced Side Effects

The side effects in the original trial were mild gastrointestinal upsets and increased breathing rate and effort that lasted no more than 20 minutes.

“This is extremely promising when you think of many traditional chemotherapy drugs. They can cause much more pronounced gastrointestinal distress and affect the bone marrow and immune system putting patients at risk for dangerous infections. This is less commonly seen in our veterinary patients, but a serious consideration in human cancer patients,” Dr. Lundberg says.

Now that pilot testing has shown the drug to be safe and effective in cats, clinical trials are the next step. To be eligible to enroll in the study, a cat must be tested to verify a diagnosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma and have blood work screening to rule out other health problems that might complicate treatment and disqualify the cat from the study.

Clinical Trial Under Way

Cats that are enrolled in the study must first have had a computed tomography (CT) scan to measure the size of the tumor. Then the cat will receive four weekly treatments of radiation and IB-DNQ. A second CT scan after the treatment period will allow researchers to evaluate changes in tumor size.

“The grant allows us to cover the costs of the study after the initial evaluation. Essentially, trial participants receive a month of cancer treatment, repeated physical examinations and blood work, and a follow-up CT scan for free,” Dr. Lundberg says. “We can also provide nutritional assistance if the cat isn’t eating, such as placing a feeding tube.”

This new anti-cancer drug provides a promising alternative to previous anti-cancer drugs that kill both normal and cancerous cells in the body, and in the process destroy healthy tissue and temporarily diminish quality of life.

“Now, anti-cancer drug development is approaching a type of ‘personalized’ medicine,” Dr. Lundberg says. “We are focusing on the unique characteristics of tumors, targeting only those characteristics in order to spare normal cells.”

Illinois researchers are hopeful that the IB-DNQ drug will prove effective against feline oral squamous cell carcinoma. If successful in cats, IB-DNQ could potentially benefit dogs and humans with similar tumors, as both species experience related types of cancer of the head, neck, and oral region.

By Danielle Engel

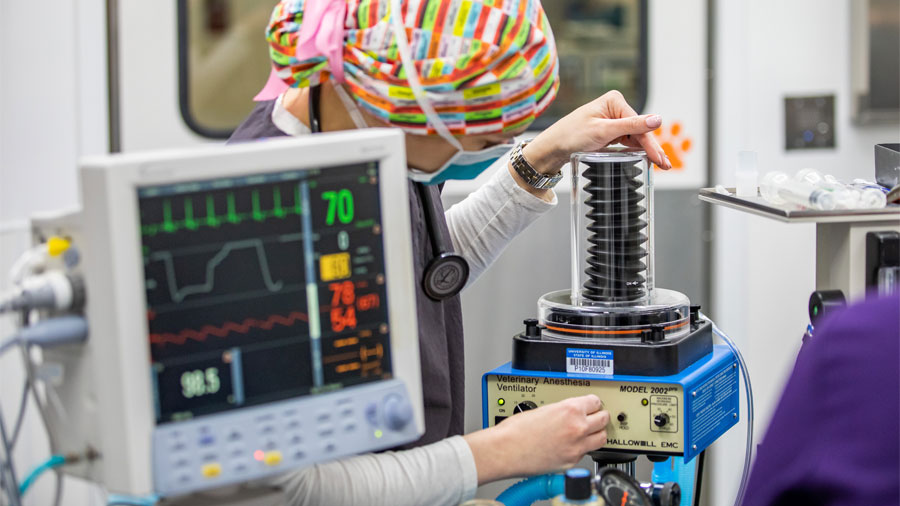

![[Dr. Alycen Lundberg works on mouth cancer in cats]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-oralcancer-lundberg.jpg)