Study Uses High-Precision Radiation Technology

Every year, 10,000 dogs in the United States are diagnosed with osteosarcoma, an extremely aggressive malignant bone tumor that typically occurs in a weight-bearing limb. Recently, Morris Animal Foundation funded a three-part study at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine to examine whether the body’s own immune system could be stimulated to eliminate osteosarcoma.

The study could lead to advances in treating not only canine patients, but children as well.

“Because there are similarities between canine osteosarcoma and human pediatric osteosarcoma, finding better treatment options for this form of cancer is especially important,” says Dr. Timothy Fan, a veterinary oncologist who has been researching osteosarcoma—particularly how bone tumors spread to other parts of the body.

He and Dr. Kim Selting, a radiation oncologist who joined the Illinois faculty in 2017, are co-investigators on the immunotherapy study. Their research will explore the combination of an immunostimulatory molecule and radiation therapy to stimulate an immune response, looking first at a cell model, then a mouse model, and ultimately dogs with osteosarcoma.

Osteosarcoma in Dogs

The cancer service at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital treats around 50 dogs with osteosarcoma a year. Large- or giant-breed dogs are most often affected; the disease very rarely manifests in cats.

“The first sign owners typically notice in their pets is lameness,” says Dr. Selting. “Animals may also have swelling in the area of the tumor. These areas can be warm and painful to the touch.”

Although osteosarcomas most often appear in one of the limbs, they can arise as a primary tumor in non-bony tissues, including the liver, kidneys, spleen, and mammary glands.

What makes osteosarcoma so deadly is its ability to metastasize (or spread) to other parts of the body.

![[Natasha with three legs]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-natasha.jpg)

Current Treatments

Radiation, amputation, chemotherapy, or some combination of these comprise the standard treatment options for canine osteosarcoma. The veterinarian works with the animal’s owner to individualize a treatment plan designed to deliver the best quality of life for the patient.

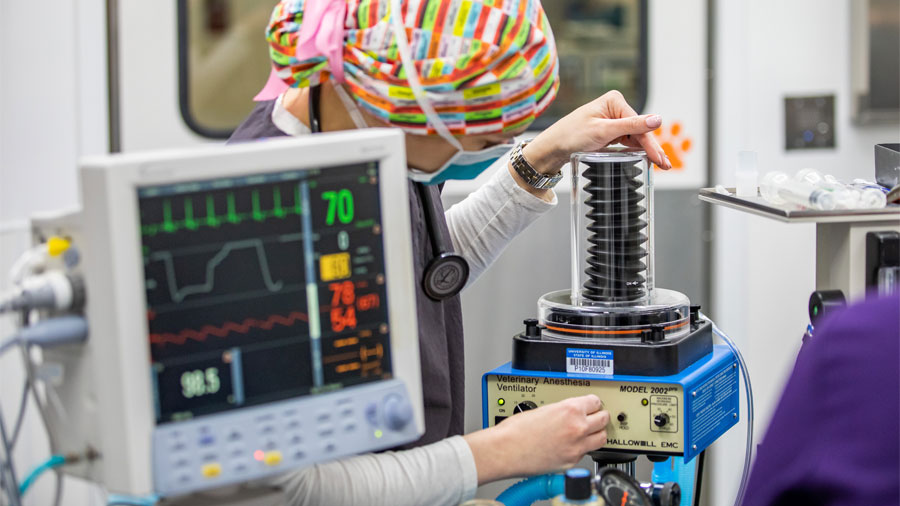

Radiation therapy uses high doses of radiation at the site of the tumor to kill cancer cells, with the goal of shrinking the tumor.

“Often the better option for patients with an extremely painful osteosarcoma is to amputate the limb, which reduces the pain,” Dr. Selting explains. Pets get along surprisingly well with only three legs.

Unlike radiation and amputation, which deliver treatment localized to the cancer, chemotherapy is a systemic treatment, attacking cancer cells throughout the body that have spread from the original tumor location.

“Chemotherapy is typically used after surgical removal of the tumor to help control the cancer as long as possible,” says Dr. Selting. Successful chemotherapy may give an animal an additional nine or more months with its family. Because veterinary oncology focuses on quality of life for the pet, chemotherapy for pets avoids the harsh side effects associated with aggressive human chemotherapy.

Immunotherapy Study

The newly funded study will look at a treatment approach that combines an immunostimulatory molecule called CPG ODN, which has shown promise as a component of cancer vaccines, with radiation. The study will take advantage of a state-of-the-art linear accelerator arriving at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital this spring.

During the first phase of the study, the researchers will examine how normal cells respond to the CPG molecule and radiation within a laboratory-controlled setting.

“This will give us a good foundation for the second phase of the study,” Dr. Fan says, “which will use mouse models of osteosarcoma to see how the CPG molecule works in a real animal.” Researchers will test various combinations of the CPG molecule and radiation.

“Because this phase takes place in a highly controlled research environment, it should provide very exact results of the therapies,” says Dr. Selting.

In the final phase of the study, findings from the first two phases will be used to develop treatment protocols for a small pilot study involving 14 dogs with osteosarcoma. Unlike the mice in phase two, the dogs will be genetically diverse, which may make results less uniform.

Translational Research

“Comparative oncology—the study of cancer treatments in multiple species—has potential to deliver tremendous medical advances,” says Dr. Fan “This field is exploding. The National Cancer Institute has designated Illinois and 21 other academic oncology programs as part of the Comparative Oncology Trials Consortium, which plays an important role in human cancer research.”

With the addition of high-precision radiation technology made possibly by the new linear accelerator, the University of Illinois advances cancer care not only for veterinary patients but also, through research, for people.

If you have any questions about osteosarcoma in pets, contact your local veterinarian.

By Beth Mueller

Image by Eliza Sánchez from Pixabay

![[photo of great dane]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-immunotherapy-trial.jpg)