shelters often euthanize heartworm-positive dogs

Reddington probably didn’t realize it, but he was in a bad spot. Not only was the dog living in an animal shelter, he had also tested positive for heartworm disease. In many cases, those two factors amount to a death sentence. But luckily for Reddington, he found an owner and an affordable treatment option through the University of Illinois shelter medicine program.

[row][column size=”6″]

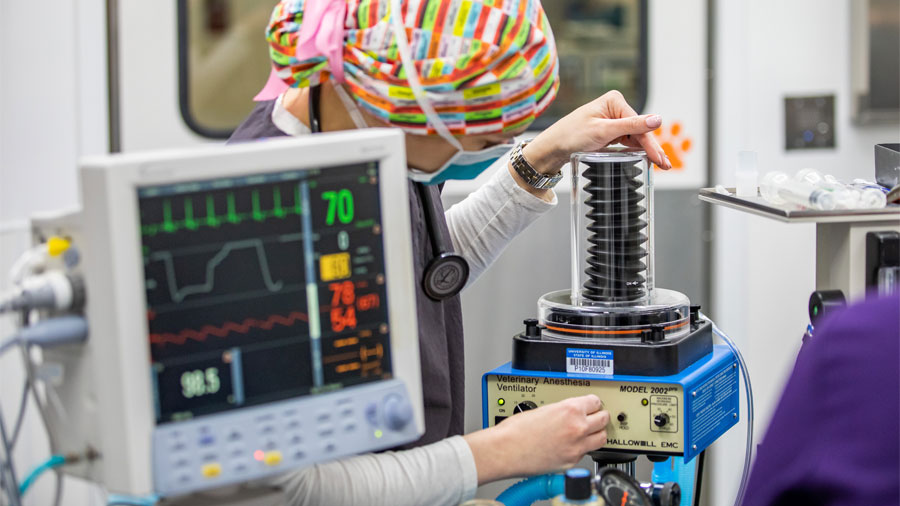

First, Reddington was adopted by third-year Illinois veterinary student Jane Do. (That’s Reddington with Jane in the photo above.) Next, Dr. G. Robert Weedon, the veterinarian who oversees the shelter medicine program, prescribed an inexpensive heartworm treatment plan that has only recently been documented in the veterinary literature.

A Devastating Disease

Heartworms are a type of parasite that invade the heart and surrounding large blood vessels. These worms are microscopic during the phase of their lifecycle when they are transmitted by mosquitoes, but can grow up to 14 inches long in your pet’s body, causing major impairment of heart function and even death. Monthly preventive medication prescribed by a veterinarian protects most owned pets from this disease.

Unfortunately, un-owned dogs do not get this protection, and heartworm infections are a big problem in shelter animals. Once the worms are acquired, treatment is both costly and dangerous to the pet.

The current standard of care for heartworm infection, according to the American Heartworm Society, is adulticide therapy. Adulticide therapy is an aggressive multi-drug therapy that requires three separate sessions to complete. The treatment itself takes about three months to eliminate the worms, but the dog cannot be retested for another six months. Adulticide therapy can be successful, but can have adverse effects, such as formation of clots that can obstruct blood vessels. Therefore, dogs undergoing this treatment are completely restricted from activity. Worms can also be surgically removed by a boarded cardiologist through a minimally invasive surgical procedure, but this is expensive and generally not feasible in shelter animals.

[/column][column size=”6″]

[callout title=”Excerpt from Statement by American Heartworm Society in 2018″]

“One of the most frequent questions we hear—especially from pet owners—is about the need from adulticide treatment for infected dogs. It’s understandable when you consider the expense of treatment and the need for multiple veterinary visits,” says [Chris Rehm, DVM, President of the American Heartworm Society]. “We also get questions from veterinarians about the AHS protocol itself, which includes pretreatment with an ML and doxycycline, followed by a month-long waiting period, then three doses of melarsomine on days 60, 90 and 91.

“Heartworm disease is a complex disease, and there are no shortcuts to appropriate treatment,” the AHS leader emphasizes, noting that the AHS protocol was designed to kill adult worm infections with minimal complications while stopping the progression of disease. “Skipping any one of these steps can affect both the safety and efficacy of heartworm treatment.”

Rehm adds that non-arsenical treatment protocols, including the “moxy-doxy” combination of moxidectin and doxycycline, have been studied in both Europe and the U.S. to better understand how to manage heartworm-positive dogs that aren’t candidates for melarsomine treatment. “Because some dogs are simply not candidates for adulticide treatment, there is a place for alternatives such as these,” he explains. “However, it’s also important for veterinarians to understand that these non-arsenical protocols have serious disadvantages, the most important of which is the length of time required to kill adult worms, during which time heartworm pathology and damage can progress. This also greatly increases the length of time the pet needs strict exercise restriction, which is problematic.”

From American Heartworm Society Releases 2018 Canine Heartworm Guidelines

[/callout][/column][/row]

“Many shelters have reluctantly euthanized heartworm-positive dogs like Reddington because of the time and expense required to treat their condition,” says Dr. Weedon.

A New Protocol

A new heartworm treatment protocol was published in the Journal of Parasties and Vectors by Molly Savadelis of the University of Georgia last fall, opening the door to a treatment option that could be feasible for shelter animals.

“Savadelis’ protocol indicates that another option is available, and it was a great choice for Reddington,” explains Dr. Weedon.

The “moxi-doxy” protocol, as it is referred to, involves the combination of two drugs many pet owners may be familiar with: Advantage Multi® for dogs (10% imidacloprid + 2.5% moxidectin) and doxycycline.

Doxycycline is an antibiotic that can be administered orally, and Advantage Multi is a common heartworm and flea preventative that is applied topically. The doxycycline is given for thirty days and the Advantage Multi is given once a month as directed on the label. After ten months the dog can be antigen tested to determine if the heartworm is still present.

“When this protocol was completed in the study, all previously infected dogs tested negative for heartworm within ten months,” states Dr. Weedon.

Reddington’s Case

When Do adopted Reddington, she worked with Dr. Weedon to administer the moxi-doxy protocol.

“My experience with this treatment was great, and I’m really pleased with it,” says Do. “I had Reddington tested at three, six, and eleven months. He tested negative at six months but was considered officially negative at eleven months!”

Traditional adulticide therapy requires strict kennel rest to reduce the chance of embolism. This therapy can be difficult to implement in a shelter setting. On the moxi-doxy protocol, the animal’s activity should be limited, but strict cage confinement may not be necessary. However, any high exertion should be avoided.

“We didn’t exercise-restrict Reddington too extensively. He wasn’t allowed to tussle around with other doggie friends or run around at the dog park for hours at a time by any means, but strict crate rest was not necessary,” reports Do.

“There are no long-term restrictions yet identified for animals that recover from heartworm after use of the moxi-doxy protocol. More data will be developed as the protocol’s use expands,” says Dr. Weedon.

‘May Not Be Appropriate for All’

Heartworm-positive patients are often classed according to severity, and many dogs in advanced stages may not live despite treatment. Presently, there is no evidence to suggest that moxi-doxy is any less effective than traditional therapy.

Dr. Ryan Fries, a boarded cardiologist at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital notes, “It is great that we continue to look for ways to treat this devastating disease. Moxi-doxy is a great protocol for some dogs and owners; however, each case is unique and this protocol may not be appropriate for all dogs in all stages of heartworm disease.”

Dr. Weedon concludes, “Moxi-doxy offers us another great tool with which to treat heartworm-positive dogs. With this protocol in a shelter setting, we can save resources and save lives.”

If you have questions about heartworm treatment, contact your local veterinarian.

By Hannah Beers

Photo courtesy of Jane Do.

![[Reddington with Jane Do]](https://vetmed.illinois.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/pc-weedon-reddington.jpg)