Do you own a gentle giant … a Great Dane, Doberman pinscher, Weimaraner, or Irish setter? These big-hearted breeds are known for their loyalty and laid-back charm, but their deep-chested conformation also carries a hidden risk that every owner should know about: gastric dilatation-volvulus, or GDV, also known as bloat.

This life-threatening emergency can strike suddenly, often with little warning. “By the time we see them in the ER, the stomach is already distended and rotated,” says Dr. Canaan Shores, a small animal urgent care veterinarian at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital. “It can become life-threatening very quickly.”

Watch for Unproductive Retching

So, what exactly is GDV, and what should owners watch for? According to Dr. Shores, GDV has a two-part pathophysiology. The first part is gastric dilation, where the stomach becomes bloated and fills with gas. The second is volvulus, which occurs when the stomach twists or rotates.

“With the experimental data and studies that have been done on this, either one can happen first. By the time we see them in the ER, they already have both.”

One of the most recognizable signs is unproductive retching. “These are dogs that look like they are trying to vomit. They’ll have the posture, make the noise, and show abdominal contractions, but nothing of significant volume comes out,” explains Dr. Shores.

If this occurs, it’s a true emergency. Owners may also notice restlessness, pacing, anxiety, and difficulty getting comfortable.

Without intervention, GDV can become fatal in as little as a few hours.

“With this disease, we see a reduction of blood flow primarily to the stomach,” Dr. Shores notes. “An important indicator of prognosis in dogs with GDV is the level of lactate on bloodwork. High lactate indicates poor perfusion, or blood flow, to the tissues.”

Initial treatment focuses on stabilizing the patient and decompressing the stomach as quickly as possible. Once stable, the dog is taken into surgery to further decompress and de-rotate the stomach. During surgery, it’s important to also check for tissue necrosis (tissue death) and to assess the condition of the spleen.

Prevent GDV with Gastropexy

“We should always do a gastropexy at the same time,” says Dr. Shores. A gastropexy, which involves suturing the stomach to the abdominal wall to prevent future twisting, is “a highly effective preventative procedure and the number one thing an owner can do to reduce the chances of GDV in at-risk patients. These dogs are repeat offenders and are prone to having another GDV if we don’t do the gastropexy.”

Fortunately, this procedure can often be done at the same time as a spay or neuter. If owners are planning to delay sterilization, Dr. Shores recommends scheduling the gastropexy separately, around one year of age, to ensure protection early in life.

If you suspect your dog may be experiencing a GDV, act immediately.

“Get in the car and drive to the nearest emergency clinic,” urges Dr. Shores. “Most emergency practices have a protocol ready to receive these cases, get them worked up, and get them treated as quickly as possible. The prognosis significantly declines if treatment is delayed.”

Gastric dilatation-volvulus is a condition where minutes truly matter, so don’t wait. Know the signs, have a plan, and talk to your veterinarian about whether a preventative gastropexy is right for your dog.

“Time is of the essence,” Dr. Shores warns. “It’s always better to have them checked out than to wait and risk hitting a point of no return.”

Your gentle giant’s life could depend on it.

By Julia Bellefontaine

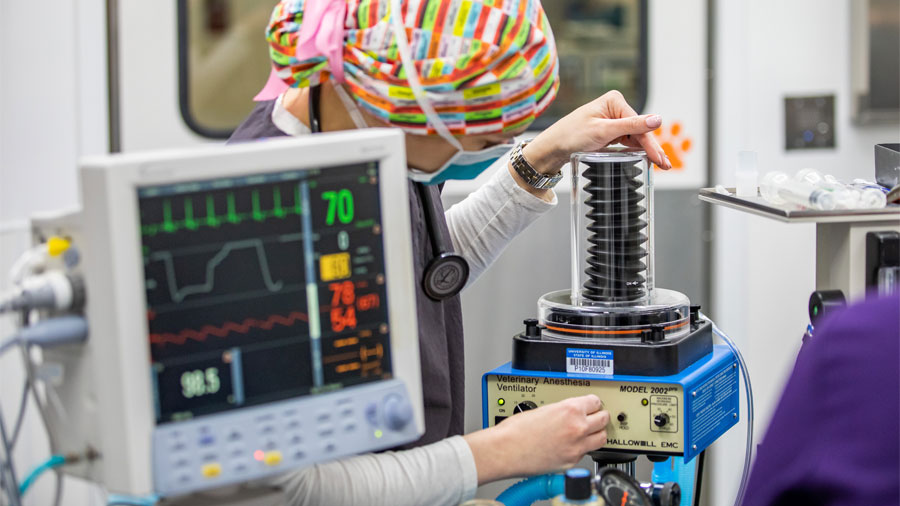

Featured photo by L. Brian Stauffer