“Spay” and “neuter” are words frequently heard by owners of a new puppy, kitten, dog, or cat visiting the veterinary clinic. While spaying or neutering may be a requirement when adopting from a shelter and even from some breeders, at other times the choice is up to the owner.

Dr. Gene Pavlovsky, a primary care veterinarian and director of the University of Illinois Veterinary Medicine South Clinic, discusses what these words mean and shares new information that could influence spay and neuter decisions.

Surgical Options for Spays and Neuters

The terms “spay” and “neuter” refer to the removal of sex organs. “Spay” refers to the removal of the ovaries and uterus from a female patient, while the term “castration” is reserved for the removal of testicles from a male patient. “Neuter” applies to the sterilization process for either male or female animals.

There are various approaches used for surgical sterilization of pets, and each approach has its own advantages and disadvantages. The owners and the veterinarian should discuss and determine which approach works best for a particular pet.

Removal of only the ovaries of a female patient is called an ovariectomy. A spay during which both the ovaries and the uterus are removed is called an ovariohysterectomy. Both procedures can come with the risk of an infection of the uterus, called a pyometra, that can occur if the uterus remains in the patient or if the surgeon leaves a stump of the uterus during an ovariohysterectomy.

A spay during which only the uterus is removed, called a hysterectomy, leaves the ovaries, which produce the female sex hormones. In these cases, the hormones produce both beneficial influences, such as continued growth and development of bones and muscles, and non-beneficial influences, such as behaviors related to being in heat and vaginal bleeding.

“No significant differences have been found in long-term problems between an ovariectomy and an ovariohysterectomy,” Dr. Pavlovsky points out. “And there is little published data on long-term effects of gonad-sparing procedures, such as hysterectomies, in dogs or cats.”

Neutering a male animal may take the form of an open or a closed castration. “The difference between the two surgical approaches is relatively minor,” states Dr. Pavlovsky. “Whether one procedure is technically easier to perform tends to be a personal choice of the surgeon.”

Options for the Timing of Sterilization

“There are three generally accepted time frames for pet sterilization: early/pre-pubertal, standard (4 to 6 months of age), and delayed,” says Dr. Pavlovsky.

In animal shelters, dogs and cats may be sterilized as young as 6 to 8 weeks old, during the pre-pubertal time frame, to make the pets more adoptable (new owners will not have to pay for the procedure) while preventing unwanted litters. The standard time frame reflects when most veterinary clinics perform the procedures when owners bring in their new pets.

“In recent years, the timing of spay and neuter has come under question as studies provided new information on risk of certain diseases,” Dr. Pavlovsky says. Each time frame has associated pros and cons that should be considered in the context of the individual pet.

An advantage of performing the surgery earlier is that younger animals tend to have fewer complications and faster recovery. However, Dr. Pavlovsky also notes disadvantages.

“Early sterilization may increase the risk of some forms of cancer and joint conditions in certain pure-bred dogs,” he says. “It can also increase the risk of joint-related disease in large dogs and of conditions such as obesity in both dogs and cats.”

On the other hand, waiting longer to perform a spay in female dogs and cats has been found to increase the risk of mammary cancer.

Unfortunately, these findings related to the timing of a spay or neuter do not add up to a single recommendation that applies equally to the general population of pets. Timing of the procedure represents another decision that should arise after a conversation between veterinarian and owner that considers the needs of a specific pet.

The Bottom Line: Talk It Over

With so many pros and cons to each surgery, as well as advantages and disadvantages of the timing of the surgery, how can an owner feel confident in making a decision?

Dr. Pavlovsky notes that the American Animal Hospital Association has issued guidelines on the veterinary care of dogs throughout their life stages. These guidelines say that male small breed dogs should be castrated around 6 months of age, while male large breed dogs should be castrated between 9 and 15 months of age, upon completion of skeletal growth. For females, small breed dogs should be spayed at 5 to 6 months of age prior, to their first heat cycle, and large breed dogs should be spayed somewhere between 5 and 15 months of age, depending upon the breed.

“Two main themes emerge from the body of available scientific research,” Dr. Pavlovsky concludes. “The first is that, overall, spayed and neutered pets live longer than their intact counterparts. The second is that data on optimal timing of spaying and neutering is fairly definitive in cats but is still far from conclusive in dogs.”

For these reasons, the decision about whether and when to spay or neuter a pet should involve a consultation with the pet’s veterinarian.

By Lauren Bryan

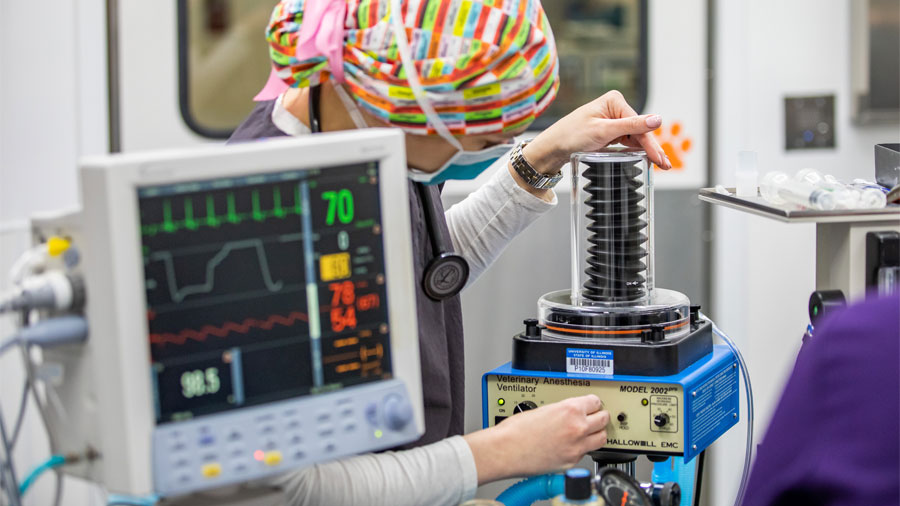

The featured photo shows an Illinois veterinary student performing a surgery to neuter a pet from a local animal shelter. Photographer: Fred Zwicky