Euthanasia allows pet parents and veterinary doctors to give a pet a peaceful end to its pain and suffering. The decision to pursue euthanasia, however, may be difficult for owners because of conflicting emotions and uncertainty about the process. Krystal Newberry, a licensed social worker and former certified veterinary technician who works at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, offers insights into what to expect regarding pet euthanasia.

What Is Euthanasia?

“In Greek, the word euthanasia literally translates to ‘good death,’ ” Newberry explains. “Euthanasia is the act or practice of ending a life in a painless and humane manner by injecting a medication that stops the heart from beating.”

Often, euthanasia occurs when the pet’s quality of life has declined, due to age or disease, and cannot be restored. Sometimes this is because treating a medical condition would require more resources than the family can give.

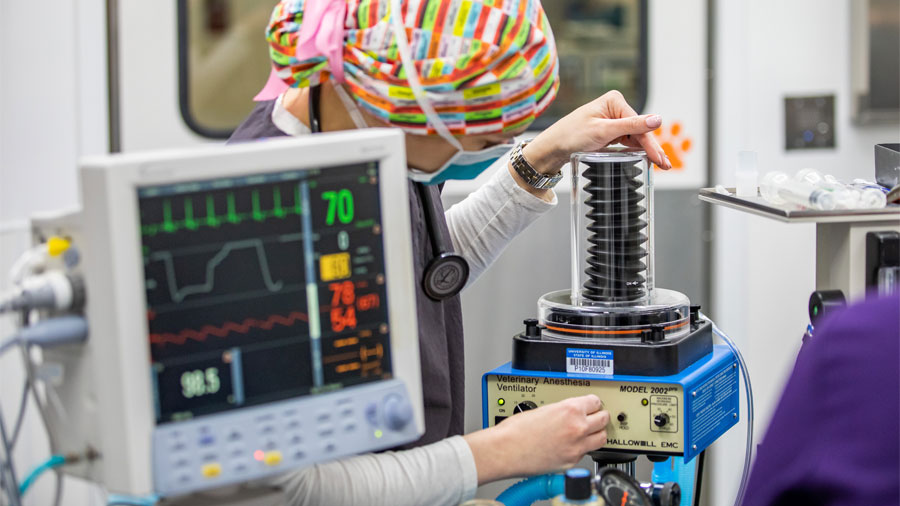

The American Veterinary Medical Association has established guidelines followed by all veterinary clinics to ensure that the euthanasia procedure prioritizes the comfort of the animal. According to Newberry, the medication administered to stop the heart was originally used as a method of anesthesia in pets.

“Your pet will not feel any pain or discomfort from the euthanasia procedure,” she assures. She also encourages owners to discuss their concerns about pain during euthanasia with their veterinary caregivers before the procedure.

How Does the Procedure Work?

The euthanasia procedure may differ somewhat from clinic to clinic. Some clinics and mobile services even offer euthanasia in the pet’s home.

In most hospitals, you can spend quality time with your pet privately in a room before the euthanasia procedure takes place. You usually have the choice to be present for the procedure or to leave your pet in the hands of the veterinary staff after saying goodbye.

If you elect to stay, the first step will be placement of an intravenous catheter in the pet’s vein. This step allows for easy administration of sedation and/or the euthanasia solution. The veterinary team may take the pet to a treatment room temporarily while placing the IV, or they may do it in the room with you present. Some clinics may elect to sedate before administering the euthanasia solution, while others may not. To ensure your pet is comfortable in their last moments, you can choose to have a conversation with the veterinarian discussing the sedation option.

When you are ready, the veterinarian will administer the solution.

“There are a few bodily activities that can occur in this moment,” says Newberry. “The pet may urinate and/or defecate. The pet may take a few, deep, last breaths. The pet may experience body movements, like twitching. And the pet may vocalize.” She also notes that some underlying disease processes cause other reactions, which the veterinarian will discuss with owners if relevant.

Because the pet is unconscious when these bodily activities occur, these are not signs that the pet is experiencing pain or discomfort.

Lastly, the veterinarian will listen with a stethoscope to ensure that the pet’s heart is no longer beating. You can then leave the room or choose to spend additional time saying goodbye to your pet.

After the Procedure

Many veterinary clinics provide owners with keepsakes created after the euthanasia to help them hold their pet’s memories close. For example, they may make an impression of the pet’s paw print in a piece of clay or using ink on paper, or they may clip a lock of the pet’s hair.

They will also ask how to care for your pet’s remains. “Most clinics offer owners the option of taking their pet’s body home to arrange for burial or cremation or of sending their pet’s body directly to a crematorium,” explains Newberry. Cremation options include group/communal cremation, which provides no ashes or the pet’s ashes mixed with ashes of other pets, and private cremation, which ensures that the owner receives only their pet’s ashes.

In some cases, owners may request to have a necropsy performed on their pet’s body. A necropsy is the animal equivalent of an autopsy in human medicine. Necropsies can identify the cause of death or provide additional information about a pet’s underlying disease process. Owners should discuss this option with their veterinarian and learn about the fees involved if this is of interest.

The University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital offers all these options for body care and memorialization. Additionally, because veterinary students are engaged in learning at the hospital, owners have the option to donate their pet’s body for teaching purposes.

“Some owners are comforted to think that their loving animal companion has a way to continue contributing positively in the world even after death by helping future veterinarians learn and develop clinical skills,” says Newberry.

“No diagnostics are performed on the donated bodies, so pet parents will not receive any feedback by selecting this option. They will also select a cremation option to be followed after the body has been used for teaching purposes.”

Euthanasia and the Multi-Pet Household

Human family members are not the only ones who may grieve after the death of a pet. “A pet parent may notice other pets at home seeming tired, depressed, or wandering aimlessly. These are normal behaviors seen in pets after the loss of a housemate,” says Newberry.

She recommends ways to make the process easier for the surviving pets. “Some veterinary clinics may allow other household pets to be present during the euthanasia. Then they can smell the process for a deeper understanding of their housemate passing,” she says. “You can also bring a blanket, toy, and/or collar home after the euthanasia for the pets at home to smell. It is believed that a pet may give off a scent at death that other pets will recognize.”

She also advises maintaining routine in the household for the benefit of the remaining pets after a euthanasia.

When Is Euthanasia the Right Decision?

“No matter what, whether you plan the euthanasia in advance or it occurs at the last minute, the moment is never easy,” Newberry says. “When I speak with pet parents, I like to encourage the family to consider quality-of-life, not only of the pet, but of the entire family.”

She recommends several quality-of-life scales that assist owners in recognizing patterns in their pet’s health: Ohio State Quality of Life Checklist, Lap of Love Quality of Life Assessment, and Grey Muzzle (an app available for Apple and Android).

These resources help owners track appetite, nausea/vomiting, activity level, ability to move/get up, general comfort, urinary and bowel movements, and even quality of fur. They allow owners to see how many “bad days” and “good days” their pets are having. When there are more bad days than good, owners often elect to euthanize.

“Another way to focus on quality-of-life is for the pet’s family. A pet’s chronic illness can be exhausting for the pet family. You may need to consider how much more time, effort, and money you can give to ensure your pet’s comfort.

“Additionally, a pet parent who is elderly or has a disability will have to consider their own ability to care for their pet’s needs at home,” says Newberry. “Care may become overwhelming. For example, it may be too demanding to help a large dog get up and go outside to the bathroom.”

Considering the entire family’s needs is not selfish, she adds. Caring for a pet can be demanding and needs to be coordinated within the household system. As with all medical decisions, speaking with your pet’s veterinarian can help you make the best choice for your situation.

By Lauren Bryan