If your pet is hurting, it may be tempting to slip two acetaminophen tablets into some peanut butter or wet food. After all, that’s what the bottle tells you to do, right?

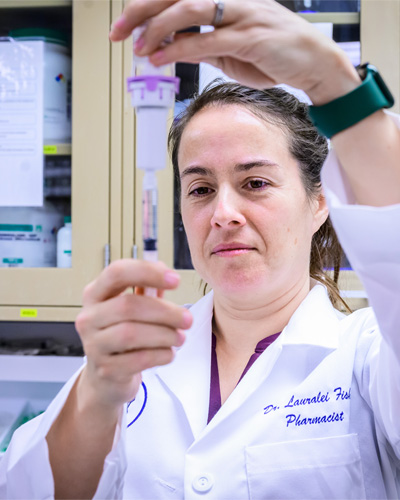

In reality, medications for animals and their dosages differ dramatically from those for humans. Dr. Lauralei Fisher-Cronkhite, veterinary pharmacist at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine, explains the importance of giving your pet only medications prescribed by a veterinarian.

What Is a Veterinary Pharmacist?

When it comes to medications, people have unique needs, and so do all the other animal species.

“Many people think that we can treat animals as if they are small people. In reality, this can be dangerous,” she warns. “Each species has its own unique physiology that affects how drugs are processed and used by the body.”

In her first year of pharmacy school, Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite learned about a specialty area called veterinary pharmacy. After completing her Doctor of Pharmacy degree, she pursued this path, becoming both a Fellow of the Society of Veterinary Hospital Pharmacists and a diplomate of the International College of Veterinary Pharmacy.

So, what does a veterinary pharmacist do?

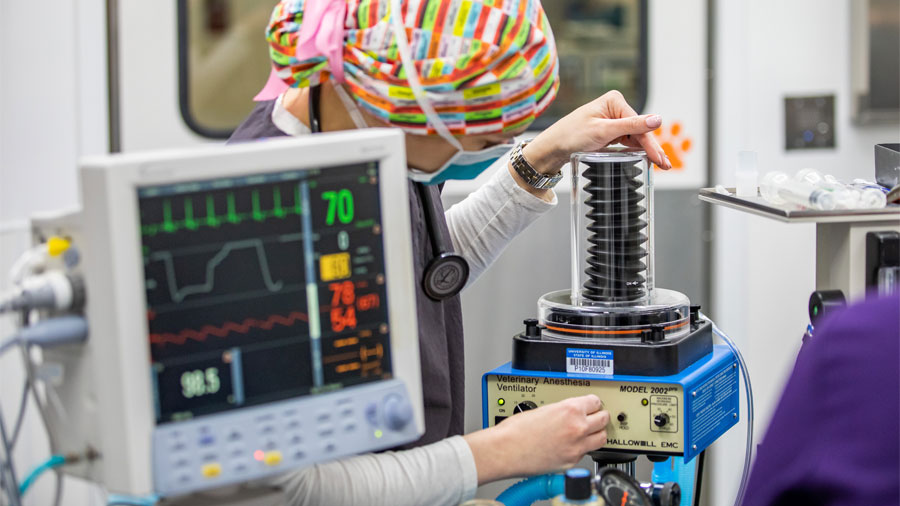

While all veterinarians receive education in veterinary pharmacology, veterinary pharmacists support and advise veterinarians and their clients. At a large facility like the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital, veterinary pharmacists oversee the medication dispensary, ensuring proper inventory, compounding, dispensing, and disposal of drugs. They also help veterinarians determine medications and dosages needed for difficult cases.

(Interestingly, veterinarians can specialize in pharmacology. Dr. Lloyd Davis, one of the founders of the field of veterinary clinical pharmacology, served as professor at the University of Illinois from 1978 to 1994. Today, Illinois faculty member Dr. Jennifer Reinhart is one of fewer than 100 veterinarians boarded in the specialty of veterinary clinical pharmacology. These specialists engage in research to advance knowledge of medications for animals.)

The Dose Makes the Difference

Several medications are used in both human medicine and veterinary medicine. These include furosemide, enalapril, diltiazem, and digoxin, which are used to treat cardiac issues in both fields. However, medications have different doses according to body weight and species. Of course, humans have different body weights and are a different species from dogs, cats, cattle, horses, pigs, etc.

“A great example of this is levothyroxine,” Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite says. “It is used for hypothyroidism in both humans and dogs. The starting dose for a dog is about 10 times higher than the starting dose for a human and is given twice as often. This is because dogs can’t absorb and use levothyroxine as well as humans. The drug also moves through dogs’ GI tract more quickly, resulting in lower concentrations of the drug.”

Physiology may also differ between humans and animals.

“Our companion animals process medications differently from humans—and differently from each other. They may have different enzymes or lack enzymes necessary to metabolize the drug,” says Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite.

Laws and Regulations

Veterinarians, like human doctors, are required to operate within a framework of laws and regulations pertaining to medication prescription and distribution. Some medications are approved by the FDA for human use but not for veterinary use, and vice versa. Many more medications are approved for use in human medicine but not in veterinary medicine. One such medication is acetaminophen (Tylenol).

“In humans, a set of enzymes breaks acetaminophen down safely—most of the time,” Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite explains. “Cats lack the major enzyme for this process. Instead, cats’ bodies follow a different pathway that breaks acetaminophen down into toxic metabolites. Acetaminophen is lethal to cats at very low doses and should never be given to them.”

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) such as ibuprofen provide another example of drugs that work for people but not for other animals.

“Human NSAIDs are generally toxic to companion animals. Ibuprofen can severely damage the GI tract, causing intestinal perforation. It can also damage the liver and kidneys,” says Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite.

Other medications may be approved for use in companion animals, but not for use in animals whose milk, meat, or eggs may be consumed by people.

Follow Your Veterinarian’s Guidance

For the health of their pets, owners should follow the directions given to them by their veterinarian.

“Your veterinarian knows what’s best!” Dr. Fisher-Cronkhite explains. “They have years of school, experience, and knowledge behind their decisions. They have chosen the medication or treatment based on the species, weight, medical condition, and history of the animal.

“Following veterinary instructions keeps your pet safe and ensures the treatment works as intended.”

When the treatment works as intended, your pet has the best possible chance at healing and recovery.

By Lauren Bryan