When squirrels in Urbana started mysteriously dying last month, public health officials quickly traced the culprit: tularemia. While this bacterial disease may not be top of mind for most pet owners, it should be—especially during warm weather months when wildlife and ticks are more active.

Tularemia is a zoonotic bacterial infection, meaning it can be passed between animals and people. It’s carried by rabbits, rodents, and ticks, and, though rare, it can affect both dogs and cats.

How Tularemia Infections Arise

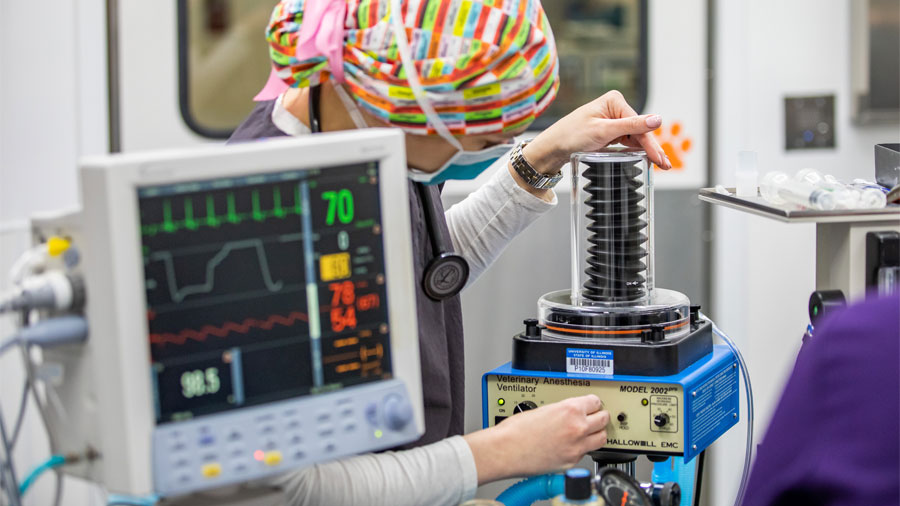

“Tularemia is a bacterial infection. It is not terribly common, and it is more common in cats than it is in dogs,” says Dr. Gene Pavlovsky, who heads the small animal primary care service at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital. It is mostly seen in wildlife, which can then transmit it to dogs and cats.

“Most commonly, rabbits and various rodents carry tularemia,” Dr. Pavlovsky explains. “Pets are often exposed by hunting, eating the flesh of rabbits and rodents, and by bites or scratches from other infected animals.

“They can also become infected from the bite of a tick or a flea carrying the bacterium that causes tularemia.”

Other, less common, ways animals can pick up tularemia include drinking contaminated water and inhaling contaminated air.

How Tularemia Is Diagnosed

One of the challenges with tularemia is that it doesn’t always present clearly. “There is not one unique sign of tularemia,” says Dr. Pavlovsky. “In most cases, the signs tend to be vague, such as lethargy, decreased appetite, vomiting or diarrhea, and signs of fever. Routine blood testing gives no definitive indication of a tularemia diagnosis.”

Because signs are so non-specific, diagnosis relies on context and clinical suspicion. “It is not difficult to diagnose,” adds Dr. Pavlovsky. “It is diagnosed through a blood test. But it may be difficult to arrive at a suspicion high enough to test for tularemia.”

Tests include PCR or antibody-based diagnostics, either detecting the organism itself or the body’s response to it.

The treatment consists of a course of an antibiotic. However, especially for cats, early diagnosis is crucial and hospitalization is often necessary.

How to Prevent Tularemia Infections

However, tularemia’s zoonotic risk means that these cases must be handled with care. “Anyone can be exposed,” warns Dr. Pavlovsky. He cites documented cases of pets transmitting the disease to people through normal interaction, such as a lick to the face.

The most important step? Limiting exposure to wildlife and other reservoirs. “Given that we know the ways in which tularemia is transmitted, contact with wild animals—especially rabbits and rodents—should be minimized,” cautions Dr. Pavlovsky. “So, keeping cats inside, keeping dogs on leash.”

He also emphasized the importance of consistent parasite prevention: “Year-round, regular flea and tick prevention with a product that is effective.”

And don’t assume an indoor lifestyle is enough protection. “A cat or a dog doesn’t even have to go outside to get fleas. People can unknowingly bring fleas inside,” he notes.

Check with Your Vet

If your pet brings home a dead rabbit or rodent, Dr. Pavlovsky says the next step is straightforward: “Contact your veterinarian. The exposure may have other implications as well, so follow their advice.”

And if a pet has had known exposure to wildlife and starts to feel under the weather, even slightly, it’s best to err on the side of caution.

“Any sign of illness, even if seemingly short-lived, should prompt owners to contact a veterinarian,” he says. “Early diagnosis can mean more effective resolution that’s quicker, and less exposure to those around the infected animal.”

If tularemia has been reported in your area, Dr. Pavlovsky recommends doubling down on prevention. “Take more precautions, more strictly. Limit your pets’ contact with the outside and make sure that they’re on flea and tick prevention.”

If you suspect your pet has or is at risk for tularemia, please contact your local veterinarian.

By Julia Bellefontaine