Dr. James Lowe, a professor of veterinary clinical medicine at the U. of I., describes the factors that influence infection with the H5N1 virus in a variety of animals.

The H5N1 virus attacks specific body systems in each species and behaves very differently in each depending on which body systems are involved, causing widespread death in some animals while barely affecting others, says University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign veterinary clinical medicine professor Dr. Jim Lowe. He spoke with News Bureau life sciences editor Diana Yates about the biological factors that influence infection and mortality in humans and other animals.

What do you think are the most important recent developments on the bird flu front?

First, we have seen expanded and sustained transmission of H5N1 in cows across the U.S. — something we had hoped to avoid.

Second, new introductions of this H5N1 strain from wild birds into poultry flocks continue, marking the fourth consecutive year of such outbreaks. Historically, we would expect a highly pathogenic avian influenza strain to circulate for only a single season, not four.

Third, since late spring 2024, we have observed transmission of H5N1 from cows to domestic poultry. However, the viruses involved in these transmissions show some variation.

How are the federal regulatory frameworks different for cows and poultry and how does that influence disease transmission?

Veterinary services within the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service have the authority to implement disease-control programs, but only for diseases officially recognized in a given species. In poultry, HPAI is a designated program disease, meaning there is a codified control program in place. This is largely to protect exports, as other countries refuse to import poultry products from regions with HPAI outbreaks.

In cattle, however, no such program exists because influenza was not previously considered a disease of cattle. Until a year ago, it wasn’t even on the radar that type A influenza viruses could infect cattle. Since H5N1 is not a designated program disease in cattle, the USDA lacks the authority to restrict cattle movement or depopulate infected herds.

As a result, H5N1 in poultry is well controlled, with no evidence of flock-to-flock transmission. In contrast, in cattle, the virus is becoming endemic. At this stage, eliminating it entirely is likely impossible. This pattern is common with emerging viruses, such as West Nile virus or SARS-CoV-2, which initially caused widespread concern but now persists at lower levels as host immunity has increased.

The virus seems to affect different species very differently. What are the factors that influence infection in different animals?

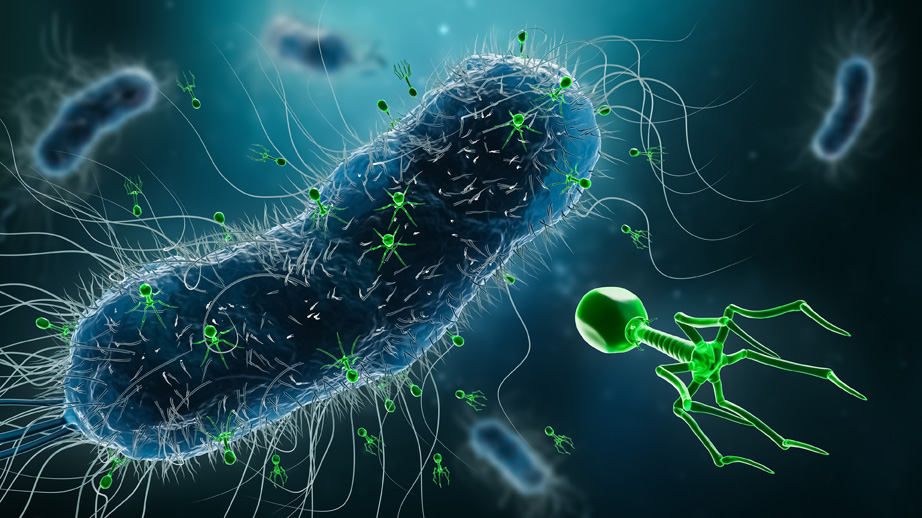

As we learned from COVID-19, a virus must bind to a specific receptor on a cell to enter and replicate. Receptors are proteins on the cell surface that are encoded by genes, meaning an organism’s genetic makeup determines its susceptibility to infection.

For influenza A viruses like H5N1, the key receptor is a sialic acid receptor. Humans primarily have one type, while birds have another. Different species have varying mixes of SA receptors, which influences disease transmission.

Initially, we believed cows lacked these receptors entirely. While they don’t have them in their respiratory tract, they do in the udder — allowing H5N1 infection.

We’ve also seen H5N1 infect marine mammals like seals which have birdlike SA receptors in their respiratory tracts, making them highly susceptible. We have also seen high rates of infection in other birds like penguins.

Pigs primarily have humanlike receptors but also possess a few birdlike ones in their respiratory tracts. The longstanding theory was that bird flu would infect pigs, then jump to humans, but instead, the predominant transmission pattern has been human-to-pig rather than pig-to-human.

In cats and many wild carnivorous mammals, H5N1 causes neurological disease rather than respiratory illness because their birdlike SA receptors are located in the brain. This explains infections in species like cats, foxes and opossums.

Humans do have some birdlike receptors, but they are deep in the lungs. This makes human infection extremely rare. However, when it does occur, the disease is severe because the virus must reach deep lung tissue to replicate effectively.

Do you think the spread of the virus to so many species and the first human death in the U.S. suggests another human pandemic is on the horizon?

Despite widespread human exposure — particularly in China, where data collection is strong — only a handful of infections have occurred. This suggests H5N1 is not well-adapted for human-to-human transmission.

Our lab collaborates with the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital as part of the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Response network. This network comprises seven centers, bringing together leading experts in influenza transmission, virology, immunology, vaccinology and zoonotic potential.

From these experts, I hear a consistent message: While we must remain vigilant for zoonotic events, there is no imminent threat of a pandemic. We have extensive knowledge of influenza, robust monitoring systems in place, and well-established pipelines to assess zoonotic risks. This is a disease we are well prepared for, supported by the expertise and collaborative networks necessary to monitor and control potential outbreaks effectively.

At this stage, H5N1 is primarily a livestock issue. While concerns about human transmission persist, the reality is that this virus is 98% a domestic livestock story and 1–2% a domestic cat story. Right now, it’s more of a food supply issue than a human health crisis.

Note: This interview with Dr. James (Jim) Lowe originally appeared on the University of Illinois News Bureau website.