Rabbit Gastrointestinal Stasis Syndrome

- Gastrointestinal (GI) stasis in rabbits is diagnosed based on clinical history and confirmation of the common clinical manifestations including reduced appetite, reduced fecal output, abdominal discomfort, and lethargy

- ALWAYS SECONDARY to an UNDERLYING CAUSE such as illness, pain, stress, or inappropriate diet that negatively impacts GI motility

- Up to 25% of rabbits presenting to practice have this syndrome

Key Rabbit Anatomy/Physiology

- Monogastric hindgut fermenting herbivores with a well-developed cecum

- Rely on cecotrophy (ingestion of cecotropes) to absorb fermentation products (amino acids, volatile fatty acids (VFA), and water-soluble vitamins)

- Fiber is ESSENTIAL for GI motility

- Diet should be >75% grass hay (e.g., timothy, orchard grass, meadow, etc.)

Presenting Complaint/Clinical Signs

- Rabbit that has not eaten OR reduced appetite for >4 hours, refuses treats, or has abnormal/reduced fecal output

- Often non-specific, variable depending on underlying cause

- Often presenting in hypovolemic shock (pale mucus membranes and delayed capillary refill time, depressed mentation, low blood pressure, low rectal temperature)

- Acute lethargy, bruxism, stretched or hunched body position, ptyalism, abdominal distension, gastric tympany, reduced borborygmi

Causes

A. Psychosomatic

- Stressors, such as hospitalization, moving, travel, or visiting friends

B. Pathologic – Secondary to any disease

- Systemic disease (kidney, liver failure)

- Pain/discomfort (oral pain, arthritis, GI obstruction, e.g., trichobezoar)

- Dehydration (patient and/or GI contents)

- Inappropriate diet (low-fiber, excessive carbohydrates, rapid diet change)

- Alterations in pH and hindgut microbial flora disruption (dysbiosis)

Triage Examination

STABILIZE ASAP IF:

- Bradycardia <140 bpm

- Hypothermia <99° F

- Distended/bloated abdomen

- TPR, mucus membrane color, CRT

- Abdominal palpation, +/- indirect blood pressure

HYDRATION ASSESSMENT:

- Normal rabbit stomach is soft

- If firm = mild dehydration

- If hard/pitting = moderate dehydration

- Increased skin turgor indicates ≥ 10% dehydration in rabbits

When to Recommend Diagnostics

- Complicated GI stasis (e.g., hypothermia, firm/taut distended stomach, bradycardia, etc.)

- >3 years of age

- Chronic course

- Hx changes in drinking/urinating

- PE findings outside of GI stasis (e.g., respiratory distress, mass, etc.)

- Never had a wellness exam

Diagnostic Work-up

- Complete medical history, diet and husbandry

- Oral Exam (5 components)

- Facial symmetry

- Facial palpation

- Laterolateral glide

- Incisor

- Intraoral (premolar/molar)

- Initial Minimum Database

- PCV/TS/BG

- Chemistry (or in house test): Assess prognostic indicators

- CBC/Chemistry/UA: Overall screen

- Radiographs (whole body)

- Assessing GI tract AND looking for underlying cause of GI stasis

- +/- Abdominal Ultrasound

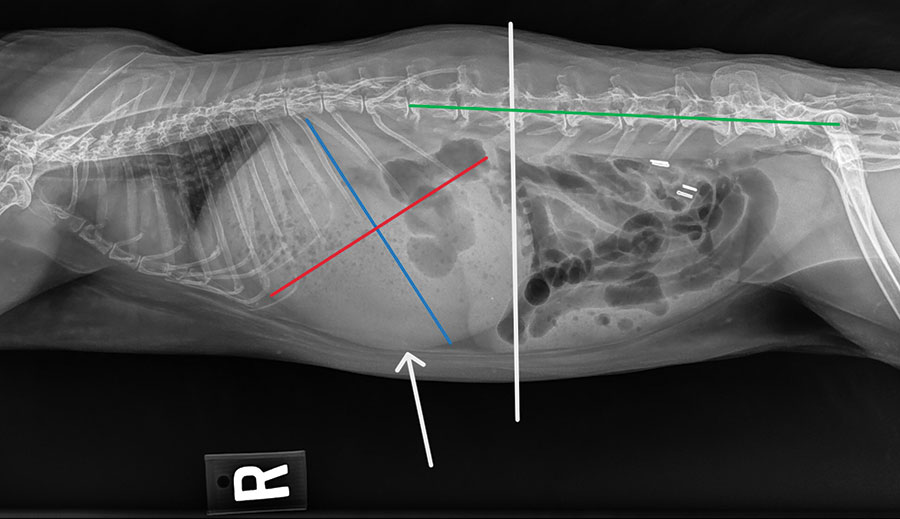

Radiographic Diagnosis of Obstruction

(Refer to image above.)

- [Gastric length (blue) + gastric height (red)] ≥ length from L1 to coxofemoral joint (green)

- Contact of stomach wall with abdominal floor (white arrow)

- Stomach extends beyond caudal L2 vertebrae (vertical white line)

- Gastric contents consisting primarily of liquid with a gas cap

- Small intestine was dilated in 67% distal GI obstructions

Reference: Debenham JJ, et al. JSAP. 2019 Nov;60(11):691-6.

Prognostic Indicators

ALWAYS TAKE RECTAL TEMPERATURE (normal: 100° to 102.5° F)

- Hypothermia: (<99° F) = 3X greater risk of death; for every 1.8° F (1° C) below 99° F, risk of death doubles

- Hyperglycemia: >300 mg/dL – Increased risk of GI obstruction

- Hyponatremia: <129 mEq/L – 2.3X greater risk of mortality

- Azotemia (elevated BUN): >24.7 mg/dL – 3X greater risk of mortality

When to Hospitalize or Refer

Complicated GI stasis (e.g., hypovolemic shock, negative prognostic indicators, evidence of GI obstruction, etc.)

Underlying disease that must be treated

Medical Management vs Surgery

Typically, medical management is recommended for suspected GI obstruction; survivability is reported in 63% to 91% of cases. Unfortunately, the prognosis is guarded for rabbits requiring surgery for GI obstruction, with 47.5% survivability.

Indications for exploratory laparotomy:

- Evidence of a GI obstruction on imaging

- And failure of medical management or declining GI motility

- And/or inability to decompress GIT

- And/or persistent abdominal pain despite analgesic therapy

The most common locations for intraluminal GI obstructions are the proximal jejunum and ileocecocolonic junction. Mats of compressed hair (trichobezoars) are the most common cause.

Consider gastric decompression (nasogastric [NG] or orogastric tube placement):

- Why? Large, distended stomach compresses intra-abdominal vessels, reduces thoracic volume, and may lead to avascular necrosis of dilated GI tract

- Consider if severe GI obstruction:

- Hyponatremia (<138 mEq/L) and severe hyperglycemia (>350 mg/dL)

- Radiographic evidence of severe gastric distension

- Risks: Aspiration of gastric contents, or accidental tissue damage during tube placement

- Benefits: Decompress, serial gas/fluid removal, NG tube feeding

Treatment Mainstays: F F A

1. FLUIDS: Rehydrate patient and GIT

- Route: most commonly SC vs IV

- Crystalloids, e.g., Lactated Ringer’s

- Maintenance fluid rate 100 ml/kg/day

- Outpatient – single SC dose 1-1.5 X maintenance

- Inpatient – intermittent SC vs IV

- Monitor for fluid overload (chemosis, epiphora, increased respiratory rate)

2. FEEDING: Nutritional support with critical care feedings by syringe

- Herbivore liquid diet syringe feeding (e.g., Oxbow Critical Care at 3 TBSP dry per kg body weight per day, divided into feedings every 6-8 hours)

- ESSENTIAL to promote GI motility – high fiber content, calories to prevent hepatic lipidosis, oral hydration

- Contraindication: initial stabilization phase, pt debilitated, hypothermic, severely dehydrated, or if suspected full or partial GI obstruction

3. ANALGESIA: Multimodal control

Controlling pain supersedes any risk of slowing GI motility with opioid administration, as long as able to provide other supportive measure for GI stasis syndrome

Opioid: Commonly via intermittent injectables, but could consider fentanyl CRI

- Buprenorphine 0.03-0.05 mg/kg IM/SC/IV q6-12h (typically q8h). Note: No data to support the oral transmucosal route.

- – Hydromorphone 0.1-0.2 mg/kg IM/IV q4-6h

NSAID: Wait for renal status; ensure hydrated or administer with fluids- Meloxicam 1 mg/kg SC/PO q24Study showed higher dose than dogs/cats required to achieve therapeutic levels. Repeated dosing study showed no renal changes on bloodwork or renal pathology following daily dosing for 29 days in healthy rabbits.

Lidocaine: IV loading dose 2 mg/kg followed by 50-100 mcg/kg/min CRI

- Pain control, promotility

- MAC sparing effect, dose-dependent

- Study showed that rabbits undergoing OVH that received lidocaine had higher GI motility, food intake, fecal output, normal behaviors and lower blood glucose levels compared with buprenorphine.

- Study showed rabbits with GI obstruction are more likely to survive if treated with a lidocaine CRI (89% vs 56%).

4. Treat underlying disease as indicated. In certain cases, other medications such as GI protectants, simethicone (Gas-X), prokinetics (metoclopramide, cisapride) may be used. Use caution with prokinetics in potential GI obstruction cases, especially since benefit is controversial.

Treatment Duration

Treatment duration is dependent on case, but typically want to see signs of improvement with onset of eating and passing feces in 24 to 48 hours of treatment. Then, hope to see continued gradual improvement over next several days and typically require treatment for 3 to 5 days, sometimes longer.

If no improvement within 48 hours or clinical decline, re-evaluation, further diagnostics, and hospitalization are warranted.

SUMMARY: GI stasis syndrome is always secondary to an underlying cause and can rapidly become life-threatening if left untreated. Early intervention is recommended.

References/Suggested Reading

- Bonvehi C, Ardiaca M, Barrera S, Cuesta M, Montesinos A. Prevalence and types of hyponatraemia, its relationship with hyperglycaemia and mortality in ill pet rabbits. Veterinary Record. 2014 May;174(22):554-.

- Debenham JJ, Brinchmann T, Sheen J, Vella D. Radiographic diagnosis of small intestinal obstruction in pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): 63 cases. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 2019 Nov;60(11):691-6.

- Di Girolamo N, Toth G, Selleri P. Prognostic value of rectal temperature at hospital admission in client-owned rabbits. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2016 Feb 1;248(3):288-97.

- Harcourt‐Brown FM. Gastric dilation and intestinal obstruction in 76 rabbits. Veterinary Record. 2007 Sep;161(12):409-14.

- Huynh M, Vilmouth S, Gonzalez MS, Carrasco DC, Di Girolamo N, Forbes NA. Retrospective cohort study of gastrointestinal stasis in pet rabbits. Vet Rec. 2014 Sep 6;175(9):225.

- Huynh M, Boyeaux A, Pignon C. Assessment and care of the critically ill rabbit. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 2016 May 1;19(2):379-409.

- Lichtenberger M, Lennox A. Updates and advanced therapies for gastrointestinal stasis in rabbits. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 2010 Sep 1;13(3):525-41.

- Mondal D., Risam K. S., Sharma S. R., AL E. (2006) Prevalence of trichobezoars in Angora rabbits in sub-temperate Himalayan conditions. World Rabbit Science 14, 33–38

- Oparil KM, Gladden JN, Babyak JM, Lambert C, Graham JE. Clinical characteristics and short-term outcomes for rabbits with signs of gastrointestinal tract dysfunction: 117 cases (2014–2016). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Assoc. 2019 Oct 1;255(7):837-45.

- Quesenberry K, Orcutt CJ, Mans C, Carpenter JW. Ferrets, Rabbits, and Rodents: Clinical Medicine and Surgery. Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2021.

- Zoller G, Di Girolamo N, Huynh M. Evaluation of blood urea nitrogen concentration and anorexia as predictors of nonsurvival in client-owned rabbits evaluated at a veterinary referral center. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2019 Jul 15;255(2):200-4.

- Schnellbacher RW, Divers SJ, Comolli JR, Beaufrere H, Maglaras CH, Andrade N, Barbur LA, Rosselli DD, Stejskal M, Barletta M, Mayer J. Effects of intravenous administration of lidocaine and buprenorphine on gastrointestinal tract motility and signs of pain in New Zealand White rabbits after ovariohysterectomy. American journal of veterinary research. 2017 Dec 1;78(12):1359-71.

- Huckins GL, Tournade C, Patson C, Sladky KK. Lidocaine constant rate infusion improves the probability of survival in rabbits with gastrointestinal obstructions: 64 cases (2012–2021). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2024 Jan 1;262(1):61-7

- Schnellbacher RW, Carpenter JW, Mason DE, KuKanich B, Beaufrère H, Boysen C. Effects of lidocaine administration via continuous rate infusion on the minimum alveolar concentration of isoflurane in New Zealand White rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). American journal of veterinary research. 2013 Nov 1;74(11):1377-84

- Steinagel AC, Oglesbee BL. Clinicopathological and radiographic indicators for orogastric decompression in rabbits presenting with intestinal obstruction at a referral hospital (2015–2018). Veterinary Record. 2023 Mar;192(5):no-.

- Brezina T, Fehr M, Neumüller M, Thöle M. Acid-base-balance status and blood gas analysis in rabbits with gastric stasis and gastric dilation. Journal of exotic pet medicine. 2020 Jan 1;32:18-26. Schuhmann B, Cope I. Medical treatment of 145 cases of gastric dilatation in rabbits. Veterinary Record. 2014 Nov;175(19):484-.