According to Dr. Hadley Gleason, a board-certified veterinary orthopedic surgeon at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana, cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) injuries are the No. 1 reason pet owners see her for surgical consultations.

The CCL in dogs is analogous to the ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) in people. This ligament connects the femur, the bone in the thigh, to the tibia, or shin bone, in the dog’s hind leg. It is located in the “knee” joint (called the stifle in dogs) and prevents the tibia from sliding forward.

“Unlike in people, CCL injuries are usually due to degeneration of the ligament over time and can result from normal daily activity,” notes Dr. Gleason. In people, ACL injuries are often related to sports or other high-intensity activity. Because this injury is degenerative in dogs, it is common for injuries to occur in both hind legs around the same time.

Diagnosing CCL Injuries

The first sign that owners may observe when their dog has a CCL injury is the dog being lame all of the sudden, according to Dr. Gleason.

“The dog is not using the leg or is limping, and that is because of pain,” she says. “I recommend checking with your veterinarian, especially if the limping lasts longer than 24 hours. There are many causes for limping and pain medication is always appropriate.”

Your veterinarian will be able to diagnose a CCL injury by manipulating the joint to check for instability. If the tibia can move independently of the femur, a CCL injury is confirmed. While this process can be done awake, it may be better for your dog to be sedated, especially for dogs that are anxious or painful.

CCL Treatment Options

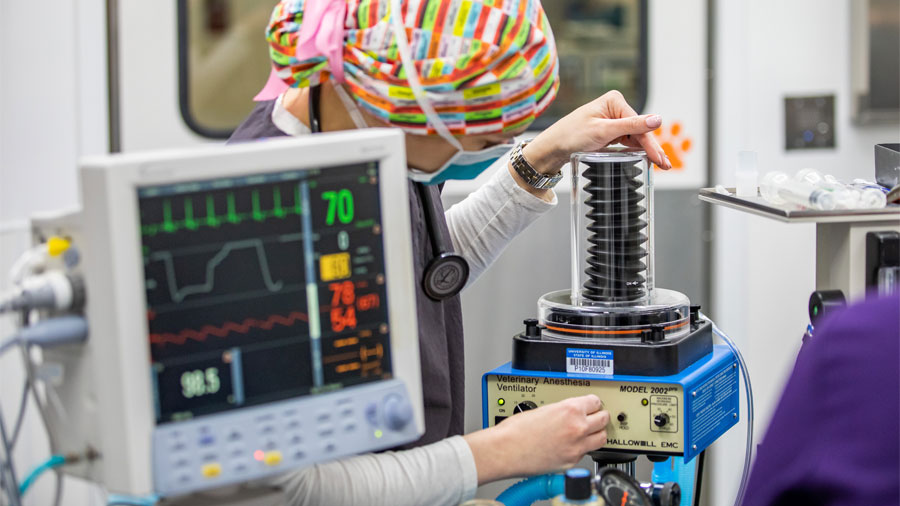

There are two treatment methods for CCL injuries. Medical management, including anti-inflammation and pain medications, along with physical therapy is a reasonable option if your dog is older, has a high risk of complications with anesthesia, or has a chronic disease that could interfere with their recovery. Medical management is also okay if surgery is not financially or logistically an option for your dog.

However, most patients will have better outcomes with surgery. The standard surgical procedures used to treat CCL injuries fall into two categories: extracapsular repairs and biomechanical repairs.

The phrase “extracapsular repair” refers to a fix that happens outside, or external to, the “capsule” of the stifle joint. It involves placing a special type of suture material outside the join “to mimic the function of the cranial cruciate ligament,” according to Dr. Gleason. “This procedure does not require significant special training or equipment, but it does not provide as much stability as other methods.”

Biomechanical repair involves opening the stifle joint and rotating and reshaping the tibia to neutralize the compressive forces. Dogs that are larger or more active typically recover better and do better in the long term with biomechanical repairs than extracapsular repairs. However, these methods are more expensive because special training and equipment is required. The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) and tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA) are both biomechanical repair procedures.

Post Operative Care

“The goal after surgery is to allow time for healing. That means creating scar tissue for extracapsular repairs or allowing the bone to heal for biomechanical repairs,” says Dr. Gleason.

Uncomplicated healing can take 6 to 12 weeks, depending on the patient. During this time, your dog will require cage rest and leash walks only. They must also avoid jumping, running, and playing so the work done by your surgeon is not damaged. They should wear an e-collar to prevent them from removing their sutures or licking the incision site, typically for about two weeks.

After the rest period, rehabilitation therapy may be helpful for your dog. Additionally, Dr. Gleason says maintaining your dog at a healthy weight is important for preventing pain and lameness.

How to Choose a Treatment

Many factors go into deciding how to treat CCL injuries. For example, smaller dogs may do better than large dogs with medical management or extracapsular repairs. In older dogs the impact of the injury on the dog’s quality of life must be weighed against the risks involved with surgical procedures. The owners of the dog play a big role in determining what is the best course of action for their pet and their family.

Those who choose the specialized surgery for their pet may discover that many veterinary specialty practices currently have waiting lists for patients seeking orthopedic surgeries. Dr. Gleason assures her clients that waiting a few months to see a surgeon will not significantly change your pet’s surgical outcome, if surgery is the best solution for your dog.

By Alaina Lamp