People are beginning to realize that dogs share a lot more with humans than just their homes and habits. Some spontaneously occurring cancers in dogs are genetically very similar to those in people and respond to treatment in similar ways. This means inventive new treatments in dogs, when effective, may also be tried in people. Dr. Timothy Fan, a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign professor of veterinary clinical medicine, is among those developing new treatments for cancer in dogs. He spoke with News Bureau life sciences editor Diana Yates about the state of such efforts and their translation to human medicine.

What types of cancers in dogs share similarities with those in people?

The National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health has formally recognized six types of cancer in dogs that also have relevance to human health. These include diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, the most common disease that we see in dogs and also the most common lymphoma in people; brain cancer, which in humans is glioblastoma multiforme and in dogs is high grade astrocytoma, which are very comparable; breast cancer in women and, correspondingly, mammary gland cancer in dogs; bladder cancer, which is much more invasive in dogs; osteosarcoma, a bone cancer that probably shares the greatest similarities between dogs and humans; and melanoma.

There are other tumors that we also study that have parallels between dogs and humans. One is called hemangiosarcoma in dogs, which is a tumor that arises from blood vessels. The comparable tumor in humans is known as angiosarcoma.

What are the commonalities between naturally occurring cancers in dogs and people?

These cancers often look very similar under the microscope, but more importantly, as we begin to better understand the genetic drivers of these cancers, we see other common traits. Cancer is a genetic disease and so if there are shared genetic origins or shared genetic mutations that give rise to these tumors, then they’re of comparative interest.

Also, biologically, we are finding that tumors in dogs may behave similarly to the corresponding cancers in humans. We are finding that some of these cancers respond similarly to the same therapies.

How is your practice engaged in treating some of these cancers in dogs?

We run a lot of different clinical trials for different types of tumors. Currently we have clinical trials in dogs looking at osteosarcoma, melanoma, B-cell lymphoma and bladder cancer. We also are exploring novel therapies for aggressive solid tumors that have spread to other sites of the body, along with very challenging tumors that affect cats.

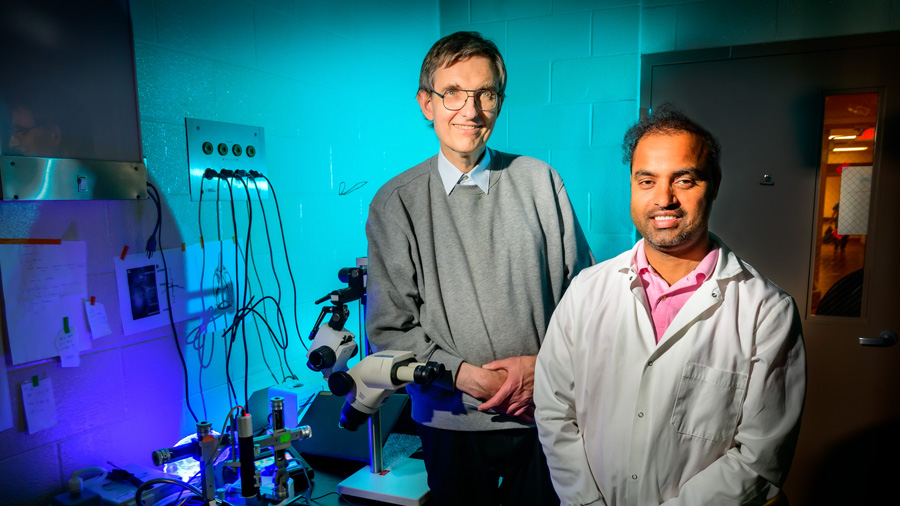

In the past, we have explored brain cancer, in an initiative that was a collaboration with U. of I. chemistry professor Paul Hergenrother. In those trials, we looked at small molecules that can penetrate the blood-brain barrier that have anti-cancer activities. That work has led to clinical trials in humans that are ongoing with a particular focus on a type of pancreatic cancer called pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

What other therapies that you first trialed in pet dogs are now being tested in human cancer patients?

We are actively involved in several immunotherapeutic approaches in pet dogs with cancer that are also being used in human clinical trials. In collaboration with Northwestern University, the trials involve adoptive cellular therapies as well as cytokines, which are inflammatory proteins that stimulate the immune system.

While cytokines are effective in fighting cancer, if given systemically or into the bloodstream, they can be very toxic. To harness cytokines safely, our new drug-delivery approaches are designed to concentrate cytokines within the tumor mass, and minimize their leakage into the bloodstream.

One approach we have investigated with collaborators from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology involves anchoring two cytokines, interleukin 2 and interleukin 12, to collagen, an abundant protein in the body that is often highly expressed in the tumor microenvironment. We evaluated this approach in combination with radiation therapy in dogs with advanced melanoma, and the trial provided remarkable responses.

One of the patients in this trial is a dog named Dezzi, who was diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the mouth. Dezzi had failed many of the conventional therapies, including surgery and radiation. The pet owners were very motivated to advance new discoveries and at the same time try new things, so they enrolled Dezzi into our trial with intratumoral collagen-anchored cytokines. And he had an incredible response.

We’re about four years out from the clinical trial, and Dezzi has not had any recurrence of the disease and is now 15 and a half years old.

Another approach that translated to human trials involves anchoring interleukin 12 into a tumor by its binding to aluminum hydroxide, a compound used in vaccines that serves as a way to depot or keep things in one area. This is a technology produced by Ankyra Therapeutics. We did the work in pet dogs prior to the launch of the human clinical trial.

Photo by Fred Zwicky

The dog trial had good responses, good safety signals, and many of the key findings that we saw in the dogs were recapitulated in the human cancer patients too. These parallel findings shared between pet dogs and people treated with anchored cytokine therapies, further highlight the unique and high-value benefits in studying cancer through a comparative oncology approach.

Where do you want to see this field go in the future?

I think we can learn from both the successes and the failures. We all want to succeed, and we’ve had some amazing achievements, but disappointments and failures are also important to informing and advancing the next steps of treating dogs and people.

What I want to see is more academic specialists — in cancer or neurology or cardiology—engaged in these high-level comparative trials. I hope more clinician scientists who are veterinarians will push the field of discovery further, with positive impacts on the human side as well as the veterinary side.

Will current cuts in research funding or structural changes at the National Cancer Institute threaten these initiatives?

Clinical trials in dogs — and humans — take money. Many foundations have some funding available to support this work, and I think we may rely more heavily on foundation support and other forms of philanthropy in the next few years to maintain research programs.

Large scale, long-ranging studies require a lot of funding, of course, and until now, we’ve relied very heavily on funding through the National Cancer Institute at the NIH. If the funding to the NCI is cut by a significant amount, then all forms of cancer research will be impacted.

The discoveries we’re making are not random. These are scientifically focused areas of investigation. We need the foundation of understanding cancers to identify druggable vulnerabilities and systematically evaluate novel therapies for new cures. We are getting results, and it would be tragic to see that progress slowed or stalled.

Feature photo by Fred Zwicky

Tim Fan and Paul Hergenrother are affiliates of the Cancer Center at Illinois, the Carle Illinois College of Medicine and the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology at the U. of I.

Dr. Fan and other veterinary oncologists across the U.S. are featured in Shelter Me: The Cancer Pioneers, a documentary on the role of veterinary oncology in pioneering new cancer treatments for humans. The documentary features leading scientists at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health and universities across the country. Shelter Me is an Emmy Award-winning PBS series produced by Steven Latham Productions and funded by Petco Love.

Shelter Me: The Cancer Pioneers is available to be streamed online at https://www.pbs.org/video/the-cancer-pioneers-jemhoc/