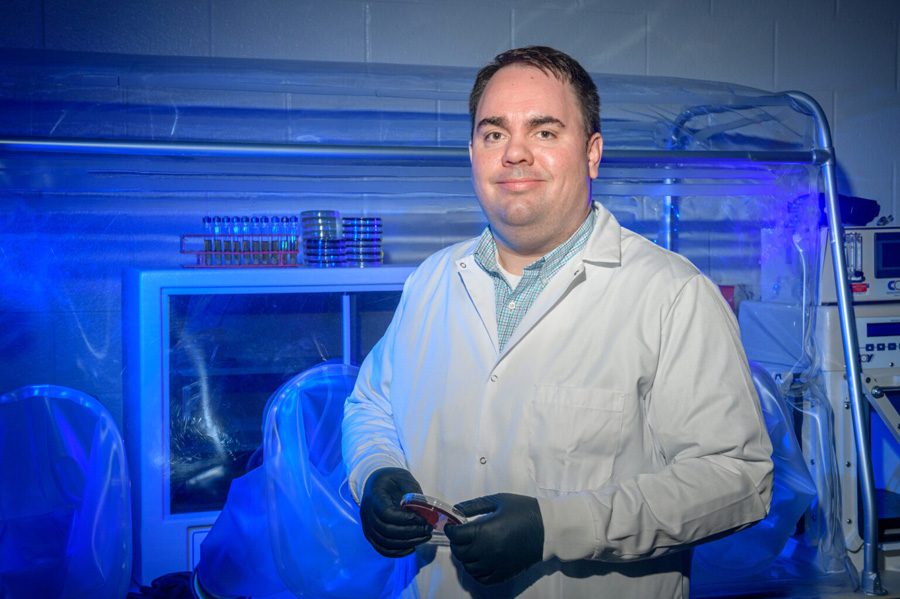

Inside the digestive tract lives a host of microorganisms known as the gut microbiome. Chris Gaulke, professor of pathobiology at the College of Veterinary Medicine, studies the gut microbiome and its role in human health. In an interview with News Bureau biomedical sciences editor Liz Ahlberg Touchstone, Gaulke talked about what roles our gut inhabitants play in digestion, immune health and cancer, as well as how what we consume affects them. Watch the video by Andy Savage.

What is the gut microbiome? Why would you want these bacteria and other microbes inside your body?

It’s a collection of the bacteria, viruses, microscopic eukaryotes and fungi that inhabit the gut, as well as the proteins and other compounds they produce.

Typically, we think of bacteria and viruses as bad things. But we want gut microbes in our bodies because they have important impacts on health. They can help train our immune system; they can help digest undigestible components of our diet; and importantly, they can help crowd out pathogens or even target them for killing in the gut so that we don’t get sick.

What role does the gut microbiome play in nutrition and digestive health?

The microbiome plays a really important role in nutrition digestive health. First, microbes can digest things that we can’t. In particular, they digest indigestible fibers. From these fibers, they can produce beneficial compounds for us, such as short-chain fatty acids, which are molecules that have anti-inflammatory properties and that our own cells use for nutrition or energy. They also help us absorb different nutrients. They can produce micronutrients such as vitamins that we can’t produce ourselves. We have to get them from our diet, or we have to get them from our microbes.

Another important component of what the microbiome does for us is to help train our immune system throughout life. Very early in life, the microbiome helps direct cells to the right places by providing them signals, and later in life, it can help stimulate our immune system and keep it active against pathogens or other microbes.

How can what we eat affect our gut microbiome?

Our diets have one of the most important impacts on the microbiome. We know that if you change from, for example, a plant-based diet to an animal protein-based diet, the microbiome changes within hours or days. The gut is just like any other ecosystem: The food components in there are what the microbes eat. So if we change those food components, our microbes also either have to change what they’re doing — what genes they’re expressing to actually chew up and eat those compounds — or other microbes that are better at doing that can come in and take over.

This can have different health impacts on us. For example, those bacteria producing short-chain fatty acids — those beneficial anti-inflammatory compounds — tend to be increased when we eat more fiber. This is where you might hear a nutritionist or your doctor suggesting that you eat fiber; it’ll help feed your microbiome.

What happens to all the microbes in your gut when you take antibiotics? What about probiotics, prebiotics or detoxes?

Some of my work has shown that it is highly dependent on the person. Some people might respond very well to specific interventions, while others might have completely opposite and sometimes even negative reactions to those interventions. So the short story is, we don’t quite know the things that are the best for everyone.

When you take antibiotics, it really depends on what antibiotics you take. Some antibiotics are broader spectrum than others, so they’ll kill more different types of bacteria. Others are very targeted. But in general, it’s going to reduce the number of bacteria that are present in your gut and other microbiomes throughout your body. This can lead to a new microbiome combination down the road, or it can go right back to what it was before taking antibiotics. It depends on the person, the spectrum of the antibiotic, and the situation in general. There are times where antibiotics actually can be good for restoring your microbiota, such as with an H. pylori infection.

Probiotics and prebiotics generally have been shown to be not harmful. But there’s not a lot of solid information out there that says that they will work in every individual. In some individuals, when they take antibiotics, if they take a probiotic or prebiotic with it, they feel better. But it’s really hard to get a probiotic to colonize a gut microbiome permanently.

Doing things in excess, like detoxes, can be beneficial, but they also can be harmful. Think about it like it’s the Sahara, and these microbes are like very small lions and gazelles. When you do a detox, it’s like setting the Sahara on fire and seeing what happens to the wildlife. And it can be good or bad. I personally tend to stay away from detoxes.

What role does the gut microbiome play in cancer, such as the rising rates of colorectal cancer in younger populations?

Microbes play a role in many different types of cancer. We know the most about gastrointestinal cancers. We know that microbial products, such as some secondary bile acids produced from metabolizing our own bile acids, can cause DNA damage, and that can lead to cancer. Microbes also can produce toxins that cause DNA damage. They can influence how quickly a cell proliferates, and that also can contribute to cancer. We found a couple species of bacteria that are generally associated with colorectal cancers and other gastrointestinal cancers. But again, this becomes very highly personalized. Some people have a lot of those bacteria and have colorectal cancer. Other people don’t, and we don’t quite know why that is yet. We don’t even know yet whether the microbes are passengers in this situation or drivers of the cancer. It could be that microbes change in response to the process of cancer pathogenesis, but aren’t actually causing that cancer. This is a very important and active area of research.

Feature photo by Craig Pessman