Parenting is not the only way moms and dads impact the behavior of their offspring. Genes matter, too. And although most of our genes are inherited in pairs—one copy from each parent—moms and dads exert their genetic influence in different ways.

According to research published in the latest issue of the journal Cell Reports, each parent has its own impact on hormones and other chemical messengers that control mood and behavior. The study focused primarily on a gene called dopa decarboxylase, which neurons need to manufacture dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline—neurotransmitters that regulate an array of functions from mood to movement.

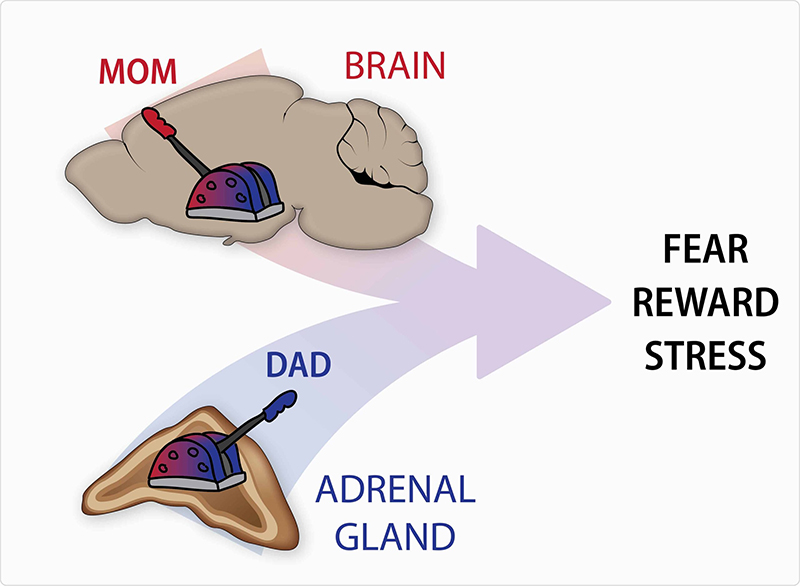

The research found that certain groups of cells in the brains of mice rely exclusively on the mother’s copy of a gene that is needed to produce essential chemical messengers in the brain called neurotransmitters. In those cells, the father’s copy of the gene remains switched off.

However, in a different organ, the adrenal gland, certain cells favor the father’s copy of the same gene. There, the gene is involved in producing the stress hormone adrenaline.

“We’re really intrigued that there is this untapped area of biology that controls our decisions,” says Christopher Gregg, PhD, principal investigator and associate professor in the Department of Neurobiology at University of Utah Health. Gaining a clearer picture of the genetic factors that shape behavior is a crucial step toward developing better diagnoses and treatments for psychiatric disorders, he says.

After identifying this unexpected switch in parental control of a single gene, Gregg’s team went on to demonstrate that it had consequences for behavior. They found that each parent’s gene affected sons and daughters differently: certain decisions in sons were controlled by their mother’s gene, whereas fathers had control over some decision-making in daughters.

“The revelation that maternal and paternal alleles of the same gene along the brain-adrenal axis could have disparate, or possibly even antagonistic, phenotypic consequences on behavior is an intriguing observation,” says Paul Bonthuis, PhD, the paper’s first author.

Bonthuis was a postdoctoral fellow in the Gregg lab before joining the Department of Comparative Biosciences at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine in 2019.

Dr. Bonthuis is continuing research into how the mother’s and father’s copy of dopa decarboxylase affect circuits involved with various aspects of social behavior with funding through an R00 award.

“The brain-adrenal axis is a very important part of mammalian biology that controls behavior and affects stress, mood, metabolism and decision-making,” Gregg explains. He says that this finding is a first step toward understanding how a parent’s genes may affect more routine behaviors and related health conditions in people, from mental illnesses and addiction to cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

Featured image courtesy of Coni Hoerndli, PhD.