When it comes to aggressive cancer in dogs, few diagnoses carry the emotional weight and effect on quality of life that osteosarcoma does. Most commonly affecting large and giant breeds, this cancer tends to target the long bones of the limbs and often appears without much warning. Though treatment options haven’t changed significantly in decades, current clinical trials to evaluate new approaches are offering hope for both pets and people.

“Osteosarcoma is cancer arising from bone,” explains Dr. Joanna Schmit, a veterinary oncologist at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine in Urbana. “It’s most common in large or giant breed dogs, and we usually see it in the shoulder, wrist, knee, or ankle.”

Dogs can also get “axial” osteosarcoma, which affects bones like the skull or pelvis.

Osteosarcoma Affects Young, Old in Pets and People

A unique aspect of osteosarcoma is its age distribution. “We see it in young dogs around 2 years old and again more commonly around age 10,” says Dr. Schmit. “That makes it a great model for human cancer, because the pattern is similar in people.”

Early signs of osteosarcoma may be subtle, but they matter. “A limp that doesn’t improve after a couple weeks of rest or pain meds should be followed up,” she says. “You may also see swelling in the wrist, ankle, or other areas. That always warrants a vet visit.”

Amputation Provides Relief

Standard treatment involves amputation of the affected limb followed by a course of IV chemotherapy. “We remove the painful part of the disease and use chemotherapy to chase down the cells already circulating in the body,” Dr. Schmit explains. “With both surgery and chemo, the average prognosis is about one year, with about one in five dogs making it to two years.”

Owners often worry about how their dog will function after losing a leg, but Dr. Schmit offers reassurance: “Most dogs are already not using the leg because it’s painful, so they’ve already adapted [to walking on three legs]. After surgery, they often find immediate relief and bounce around, happy to have it gone. Dogs can do agility, continue working–it’s not a poor quality of life.”

Osteosarcoma Trial: Immunotherapy

While chemotherapy remains a cornerstone of treatment, researchers at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital are also exploring immunotherapy options. Unlike chemo, which is cytotoxic and aims to kill cancer cells directly, immunotherapy activates the dog’s own immune system to fight the disease. Side effects are generally mild—fever, swelling, or lethargy—and often indicate that the treatment is working.

One current clinical trial involves a personalized tumor vaccine. “We amputate the limb, culture the tumor cells, and create a vaccine specific to that tumor in that dog,” says Dr. Schmit. “It’s a more targeted approach, using markers that the immune system can recognize more easily.”

Not all trials require amputation. Some involve radiation therapy for pain management in cases when surgery isn’t pursued. The clinical trials office at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital currently offers more than a dozen active trials for eligible patients with cancer.

Owners Have Options

For owners considering clinical trials, the process is often less daunting than expected. “Owners usually cover the cost of diagnosis to determine eligibility, but once enrolled, most trials are partially to fully funded, including treatment, bloodwork, and follow-up,” she says. Some even offer financial incentives to apply toward continued care.

Beyond helping their own pets, owners whose pets participate in clinical trials contribute to the future of cancer care—not only for animals, but for people.

“We’re not ‘experimenting,’ we’re discovering,” Dr. Schmit emphasizes. “These therapies are backed by solid science and regulatory oversight. Every trial gets us closer to treating cancer more effectively.”

Her biggest advice to owners? Talk to a veterinary oncologist early. “Some families want to pursue aggressive treatment, while others may want to focus on comfort and quality time,” she says. “It’s a personal decision, but having all the information helps owners feel confident in whatever path they choose.”

By Julia Bellefontaine

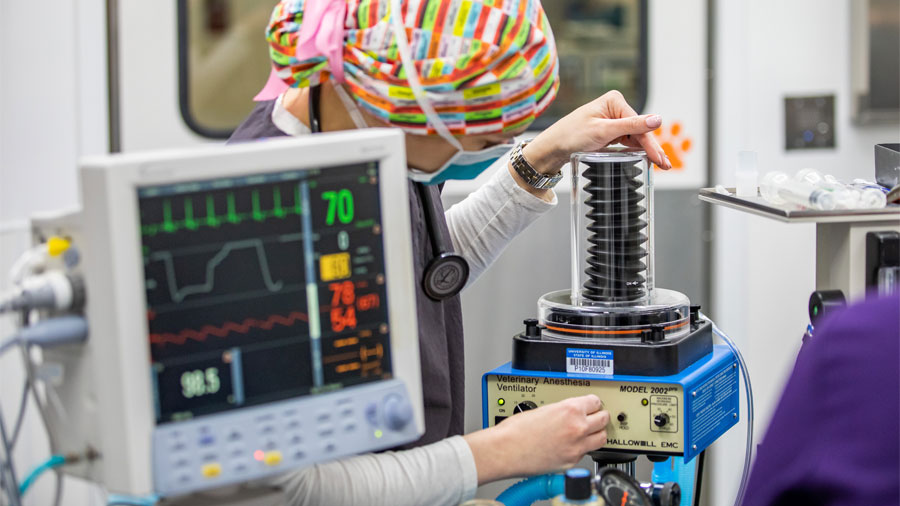

The featured photo, taken in 2023, shows two canine osteosarcoma patients who underwent amputations. Their care team and owners celebrated the dogs’ final chemo treatments by ringing the bell and giving both dogs lots of treats.