A new minimally invasive treatment option called cystoscopic laser lithotripsy is changing the game for pets with bladder and urethral stones. The University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital is among the first veterinary hospitals in the U.S. to offer lithotripsy using state-of-the-art thulium fiber technology.

“Historically, bladder stones were removed surgically or, for larger dogs, via laser therapy,” says Dr. Joseph Bruner, a board-certified small animal internist at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine. “We now offer the newest laser technology, which allows us to treat most dogs and female cats noninvasively. No surgical incisions or sutures are involved, making pets’ recovery faster and easier.”

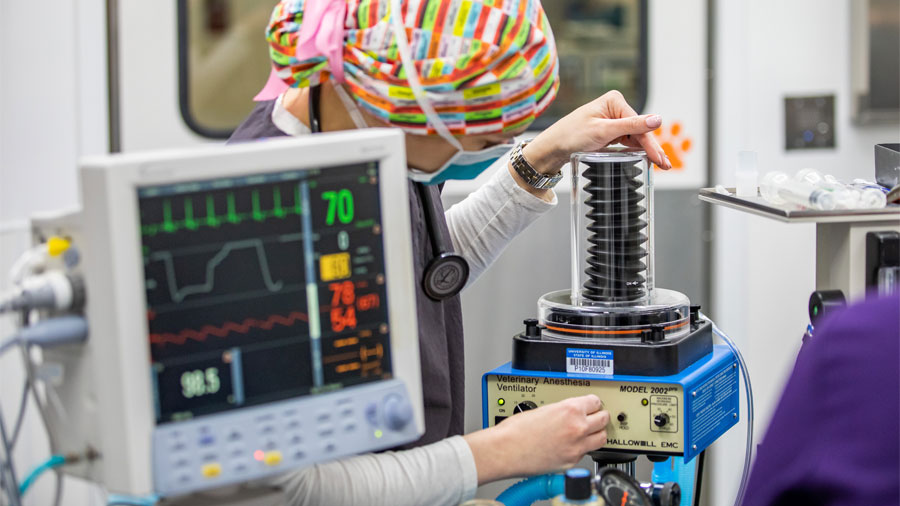

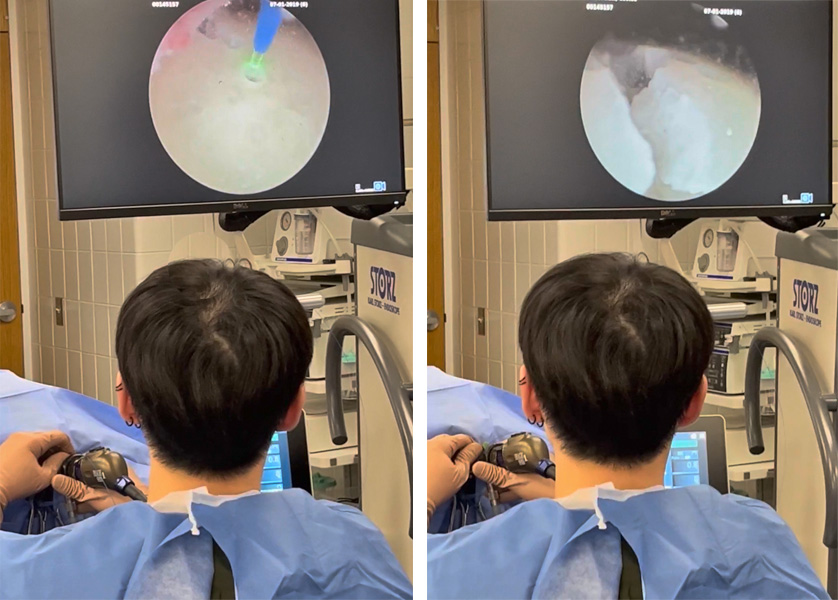

The procedure uses a thin scope and a tiny laser fiber to target and break apart bladder or urethral stones while the patient is under anesthesia or heavy sedation.

“The laser beam shatters the stone into small pieces that can be flushed out,” explains Dr. Bruner.

New Laser More Precise

This advancement is possible thanks to the thulium fiber laser. This newer generation laser is more energy-efficient and precise than previous systems.

“The holmium laser was the workhorse for years,” Dr. Bruner says, “but it required a lot of power and produced heat that could cause tissue damage.

“The thulium laser uses less energy and generates less heat. Since the fiber is smaller, we can now treat dogs anywhere from 15 to 20 pounds or more, and female cats around 10 pounds or more, noninvasively. Before, laser lithotripsy was an option only for large dogs.”

The ability to perform this procedure without surgery is a major step forward, especially for patients with recurrent stones. “For pets that keep getting stones, this gives us a way to remove them without putting those pets through multiple surgeries,” explains Dr. Bruner.

When to Choose Laser Lithotripsy

Not every patient is a candidate, though. “The ideal cases are pets with five or fewer stones, or one large stone that can be fragmented and flushed out in a single session,” Dr. Bruner notes. “If there are too many stones or the stones are very large, surgery may still be the better option.”

Additionally, the procedure cannot be performed on male cats because their urethras are too narrow.

The procedure is performed under anesthesia, and pets typically go home the same day.

“We always do a consultation first to make sure the patient is a good candidate,” he says. “Once cleared, the patient will typically come in for the procedure the next day and go home that evening.”

Side effects are generally mild. “Some pets may have a little blood in their urine or mild discomfort after the procedure,” Dr. Bruner explains. “We monitor for infection, since stones can harbor bacteria, and we usually prescribe antibiotics afterward to help prevent issues.”

While costs vary depending on case complexity, Dr. Bruner says it’s comparable to the cost of a traditional surgical procedure done at a general practice. With noninvasive cystoscopic laser lithotripsy, however, there’s no incision, which minimizes pain and speeds recovery.

Management to Reduce Risk of Bladder Stones

As with all bladder stone cases, long-term management is key.

“Some stones simply can’t be prevented due to genetics or metabolism, but diet and infection control are critical,” Dr. Bruner clarifies. “We always recommend a nutritionally balanced commercial diet and close follow-up with your veterinarian.”

Dr. Bruner encourages owners to ask about non-surgical treatment options if their pet develops stones.

“Our internal medicine service is introducing noninvasive and interventional procedures,” he says. “If your pet is diagnosed with bladder stones, talk to your veterinarian. Laser lithotripsy could be a good alternative for your pet.”

By Julia Bellefontaine

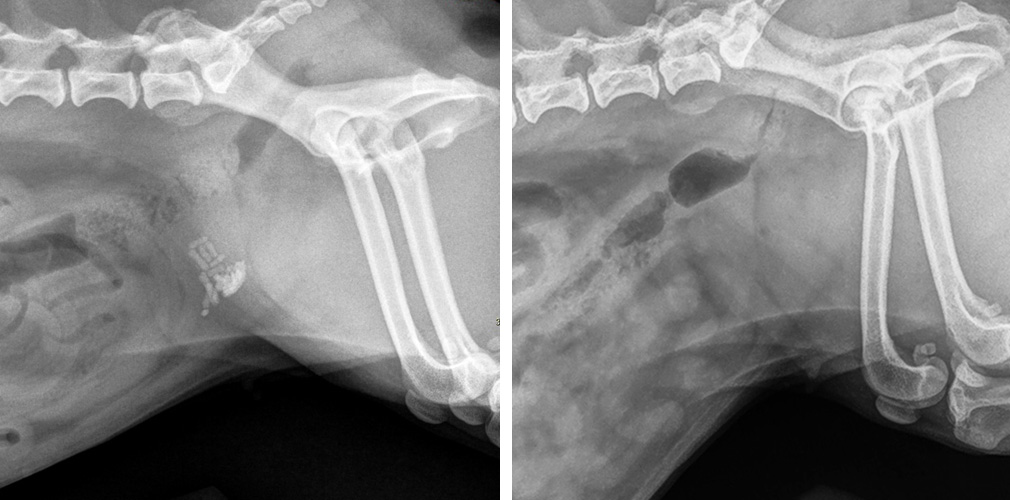

The featured image shows radiographs of a dog with bladder stones (the pile of little white objects at center) at left, and the same dog after the stones have been removed non-invasively via laser lithotripsy.