This is the story of Soot and Shepard, two male cats born to the same litter and adopted by a loving family. Tragically, Soot was lost to an unexpected and unnamed disease in April 2024. Then, three months later, 10-month-old Shepard began showing signs of disease.

Dr. Katelynn Ondek, a veterinarian pursuing a specialty credential in neurology and neurosurgery, oversaw Shepard’s care and explains how experts at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Urbana identified and treated his illness, which turned out to be feline infectious peritonitis (FIP).

Clinical Signs of Feline Infectious Peritonitis

While Shepard’s signs immediately made his care team concerned for FIP, his littermate’s history was what spurred the family into quick action.

“In March 2024, Soot developed clinical signs of limping on his right [rear leg], losing control of bowel movements and urination, and [losing interest in food],” Dr. Ondek says.

His signs progressed over the month to seizures, hypothermia (low body temperature), and bradycardia (slow heart rate). Ultimately, he was taken for emergency care and had to be euthanized when the doctors could not stabilize him. Although definitive diagnostic tests for Soot are still pending, his preliminary results are strongly supportive of FIP.

“The family’s tragic experience with Soot enabled them to recognize Shepard’s clinical signs and get him hospitalized for treatment as soon as possible,” Dr. Ondek points out.

FIP: Viral Origins

Feline enteric coronavirus often lurks in multi-cat environments. (“Enteric” means relating to the intestine.) Most of the time, this virus does not cause outward signs of disease in infected cats. However, a subset of infected cats become sick when a mutated form of that virus moves from the gastrointestinal tract to the white blood cells.

“FIP arises from a mutation in the feline enteric coronavirus, for reasons which are not well understood,” Dr. Ondek explains. While FIP is not a contagious disease, the feline enteric coronavirus is spread via fecal-oral transmission. Additionally, studies show that FIP has a genetic component. It is not uncommon for multiple cats from a single lineage to be affected.

There are two distinct forms of feline infectious peritonitis: the “dry” or non-effusive form, which can present as neurologic problems, and the “wet” or effusive form, which results in an accumulation of fluid in bodily compartments. Shepard and Soot had neurologic FIP.

Shepard’s signs began on July 31 with green nasal discharge and wheezing. Two days later, he became lethargic and showed a decreased appetite. The next day, neurological signs, including stiff back legs, a wobbly gait, and splaying of his legs, appeared. That’s when his family took action.

Diagnosis and Treatment

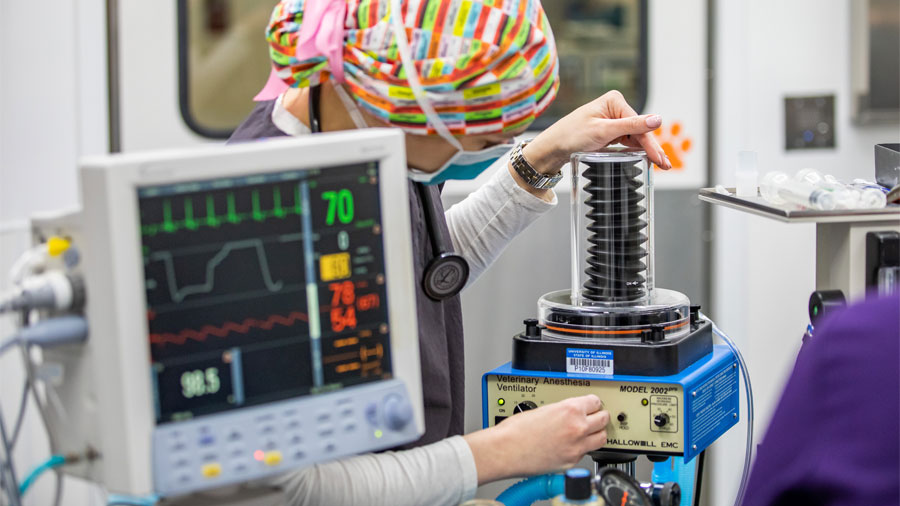

Upon arrival at the emergency room in the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Shepard was stabilized. Later clinicians transferred him to the neurology and neurosurgery service for diagnostic tests, including blood work and an MRI.

“The MRI allows us to look at the gross structures of the brain and spinal cord. In Shepard, it revealed an infection or inflammation of the tissue around his brain and spinal cord (meningitis). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis lets us look microscopically at the nervous system, and Shepard’s sample was positive for FIP,” Dr. Ondek explains. The ER started Shepard on supportive care and antibiotics. Next, the hospital’s neurology department administered a steroid to reduce the inflammation within his central nervous system. He also required a blood transfusion during his visit.

Despite these interventions, Shepard continued to decline until he received a treatment that had been previously unavailable to FIP cats: legally-sourced antiviral therapy.

“This is the first neurologic feline infectious peritonitis case that has been legally treated at [our hospital] with the injectable antiviral, remdesivir,” she says. He has since been transitioned to oral GS-441524, which just became available from Stokes Pharmacy for veterinary use in June 2024.

Prognosis: Good

Shepard began to improve within 24 hours of starting remdesivir. After four days of treatment, he was running around the treatment room with only mild incoordination. Shepard was discharged from the hospital after eight days of hospitalization. According to follow-up videos from his family, he is now back to being a typical (if slightly wobbly) 11-month-old kitten.

As recently as five years ago, feline infectious peritonitis was considered a fatal disease. However, with remdesivir and the related antiviral GS-441524, the survival rate ranges between 50% and 100%.

Remdesivir became a well-known drug for treating COVID-19 in humans. It was approved by the FDA for veterinary use in 2022. However, remdesivir “has been nearly impossible to obtain in veterinary hospitals,” says Dr. Ondek. “We are very fortunate that we were able to obtain this medication from Carle [Hospital].” Still, at $775 per 100-mg vial, this drug remains cost-prohibitive for veterinary use.

New Medication a ‘Game-Changer’

“The new compounded oral medication from Stokes, which is identical to the Bova formula used in the UK and Australia, was just legalized in June 2024 and will be a game-changer for veterinary medicine moving forward,” she says.

Dr. Ondek and her colleagues believe Shepard’s treatment with remdesivir had a huge impact on the likelihood of recovery. “According to previous studies, cats that survive the first two days have a greater than 80% chance of long-term survival with antiviral treatments,” says Dr. Ondek.

Currently, the recommended course of antiviral treatment is 84 days. Relapse is possible, either during or after the initial treatment period. Additionally, some neurologic FIP cats have permanent, non-progressive neurologic deficits despite being otherwise fully recovered.

“Shepard is not out of the woods yet, but we are all rooting for him and will be following him closely over the next few months.”

By Lauren Bryan