Our week was a little slow in terms of sample accumulation. We only had 12 new turtles to sample for the whole week. To put this number in perspective, our second week we obtained 53 samples (the highest amount in one week thus far). Many of the turtles we encountered we had previously worked up and we are only sampling each turtle once in a given 30-day period.

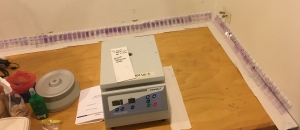

Last week we said we reached over 100 samples but what on Earth are we doing with all this blood and all these swabs? Every day after we finish up in the field and when everyone else goes home we do this little thing called lab work. First thing when we get back is make sure all of our samples have dates written on them. Swabs for DNA extractions and blood for PCR  goes in the freezer to be used at a later date – these are tests not needed to be done day of collection. We then spin the blood collected for plasma in the centrifuge to separate the red blood cells from the plasma itself and collect it into a new tube (which is then stored to be kept for a later date). Each day we rotate who

goes in the freezer to be used at a later date – these are tests not needed to be done day of collection. We then spin the blood collected for plasma in the centrifuge to separate the red blood cells from the plasma itself and collect it into a new tube (which is then stored to be kept for a later date). Each day we rotate who  does what tests so that we can do them all and not getting stuck reading hemocytometers every day. One person generally does the plasma, PCV/TP and blood smears while the other does hemocytometers.

does what tests so that we can do them all and not getting stuck reading hemocytometers every day. One person generally does the plasma, PCV/TP and blood smears while the other does hemocytometers.

Hemocytometers

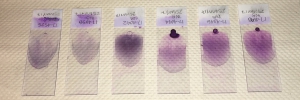

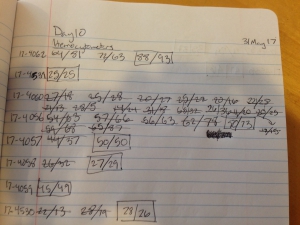

In general, this test is used to count white blood cells. We use a pink stain called phloxine that stains heterophils and eosinophils; the most abundant white blood cells in reptiles. An automated counter is  commonly used in mammals that have neutrophils. A precise amount of blood is mixed with a precise amount of stain for ten minutes. We then load the fluid into a hemocytometer, which is essentially a microscope slide with two chambers each with an etched grid. Once loaded, this stands for ten minutes before being viewed under a microscope. The stained white blood cells appear bright pink and those within the etched grid are counted. Both chambers must have counted amounts within 10% of each other, or else it must be re-made. Sometimes certain samples have to re-made over and over again (example shown in the image below) which can get frustrating but are a testament to the validity of the test in that we can be quite confident in our numbers when we do get amounts within 10% of each other. Our technique is getting better and we are not having to re-make as

commonly used in mammals that have neutrophils. A precise amount of blood is mixed with a precise amount of stain for ten minutes. We then load the fluid into a hemocytometer, which is essentially a microscope slide with two chambers each with an etched grid. Once loaded, this stands for ten minutes before being viewed under a microscope. The stained white blood cells appear bright pink and those within the etched grid are counted. Both chambers must have counted amounts within 10% of each other, or else it must be re-made. Sometimes certain samples have to re-made over and over again (example shown in the image below) which can get frustrating but are a testament to the validity of the test in that we can be quite confident in our numbers when we do get amounts within 10% of each other. Our technique is getting better and we are not having to re-make as  many multiple times. The number of cells in the chamber can be used to calculate concentration of white blood cells in the sample. Measuring this concentration provides data on general health status of the animal. Although there is not a lot of information discussing general health in Blanding’s turtles, abnormally high or low counts are typically known to be indicative of disease.

many multiple times. The number of cells in the chamber can be used to calculate concentration of white blood cells in the sample. Measuring this concentration provides data on general health status of the animal. Although there is not a lot of information discussing general health in Blanding’s turtles, abnormally high or low counts are typically known to be indicative of disease.

PCV/TP

Packed Cell Volume (PCV) and Total Protein (TP) are standard lab tests performed in most veterinary clinics that are inexpensive but informative.

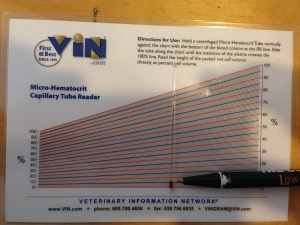

PCV measures the amount of red blood cells in relation to the total volume of blood. Blood is comprised of proteins, vitamins, minerals, red blood cells, white blood cells, clotting factors, hormones, and a host of other things that are transported throughout the body so red blood only make up a percentage of the total blood in the body. To measure this percentage we collect blood into a small thin tube called a hematocrit tube, cap one end with clay to avoid blood leaking out, place the tube in a centrifuge to spin the blood fast enough to separate plasma, white blood cells, and red blood cells. Plasma includes  proteins, hormones, vitamins, minerals and water and typically forms a clear layer of fluid that takes up the majority of the hematocrit tube. A buffy coat layer can sometimes be seen between the red blood cells and the plasma and is a thin white layer comprised of white blood cells and platelets. A layer of red blood cells, the layer we are measuring, will have been pushed to the bottom of the hematocrit tube and clearly defined. We take this tube and lay it on a chart that has different percentages demarcated. We line the bottom of the red blood cell layer with the bottom line, the top of the plasma layer with the top line, and read the line between the red blood cells and the buffy coat (if it is visible). This line gives us the percentage of red blood cells in the blood that can indicate abnormalities in an animal such as dehydration or blood loss.

proteins, hormones, vitamins, minerals and water and typically forms a clear layer of fluid that takes up the majority of the hematocrit tube. A buffy coat layer can sometimes be seen between the red blood cells and the plasma and is a thin white layer comprised of white blood cells and platelets. A layer of red blood cells, the layer we are measuring, will have been pushed to the bottom of the hematocrit tube and clearly defined. We take this tube and lay it on a chart that has different percentages demarcated. We line the bottom of the red blood cell layer with the bottom line, the top of the plasma layer with the top line, and read the line between the red blood cells and the buffy coat (if it is visible). This line gives us the percentage of red blood cells in the blood that can indicate abnormalities in an animal such as dehydration or blood loss.

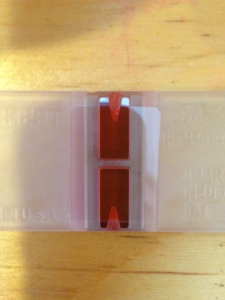

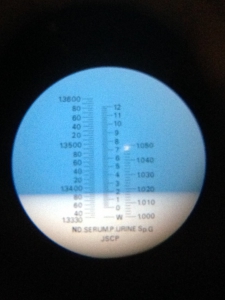

Total Protein (TP) is then measured by breaking the hematocrit tube above the buffy coat (in the plasma portion of the tube) and pouring the plasma onto a refractometer to measure the amount of proteins in the blood. The blue plate is what the plasma is poured onto and when you look through the end of the refractometer, this is the image you see. I recorded the reading below as 1.8 g/dl. TP can indicate abnormalities such as dehydration, liver disease, hemorrhage, or kidney disease.

Both of these tests are cheap, easy to run, and can give us a lot of data. For our project, the baselines of these tests have not been established for Blanding’s turtles and so instead of diagnosing turtles with problems like dehydration, we are looking to establish a range of normal values for a healthy population of Blanding’s.

John’s High: This week I got to put my kayaking skills to the test as two of the turtles that we track were found in a river! We are currently in the heart of Blanding’s turtle nesting season and so we are monitoring these egg-laying ladies very closely (we track each turtle TWICE a day). The goal is to keep a close eye on these turtles until they lay their eggs so that we know where their nest is and can monitor it over the next few months. Because the turtles I was tracking were in the river though, this meant that I had to kayak down to find them and follow them in case they decided to nest on the opposite bank of the river. So on Saturday night, around 7 pm, while most people were gearing up for a night on the town, going out to a movie, or settling in for SNL and pizza, I was squeezing into my kayak with my waders on and my telemetry equipment (tracking antenna and receiver) in hand ready to find my turtles. Blanding’s turtles nest at night, meaning that I needed to check on them for a few hours to see if they would go on land and start digging a hole to lay eggs in. I found both turtles a little after sunset still sitting in the water near the banks of the river. On my way out to them I almost ran over a very disgruntled beaver (I hope we have kayak insurance), and heard a coyote howl on the opposite side of the river. I sat in my kayak and waited for something to happen under a large, yellow moon with frogs croaking and more stars out than I had

close eye on these turtles until they lay their eggs so that we know where their nest is and can monitor it over the next few months. Because the turtles I was tracking were in the river though, this meant that I had to kayak down to find them and follow them in case they decided to nest on the opposite bank of the river. So on Saturday night, around 7 pm, while most people were gearing up for a night on the town, going out to a movie, or settling in for SNL and pizza, I was squeezing into my kayak with my waders on and my telemetry equipment (tracking antenna and receiver) in hand ready to find my turtles. Blanding’s turtles nest at night, meaning that I needed to check on them for a few hours to see if they would go on land and start digging a hole to lay eggs in. I found both turtles a little after sunset still sitting in the water near the banks of the river. On my way out to them I almost ran over a very disgruntled beaver (I hope we have kayak insurance), and heard a coyote howl on the opposite side of the river. I sat in my kayak and waited for something to happen under a large, yellow moon with frogs croaking and more stars out than I had  seen in a long time. It was exhilarating to be in the middle of so many animals at once and to be sharing a night with them while I waited for my turtles to climb up on land. But unfortunately both turtles decided not to nest that night and so, with only a headlamp and the moon to light the way, I paddled back up the river. Later on that night, another turtle near Lake Michigan was experimentally digging holes and so two of my colleagues and I sat and waited on the dunes overlooking the lake to see if she would lay eggs. She decided not to nest that night either, but I will never forget the peace I felt while sitting on those dunes with the moon reflecting off the lake and the anticipation of being able to witness a rare event in nature making it all worthwhile. This night was truly was an incredible experience that I hope I get to enjoy again some day and thanks mom, kayak camp finally paid off!

seen in a long time. It was exhilarating to be in the middle of so many animals at once and to be sharing a night with them while I waited for my turtles to climb up on land. But unfortunately both turtles decided not to nest that night and so, with only a headlamp and the moon to light the way, I paddled back up the river. Later on that night, another turtle near Lake Michigan was experimentally digging holes and so two of my colleagues and I sat and waited on the dunes overlooking the lake to see if she would lay eggs. She decided not to nest that night either, but I will never forget the peace I felt while sitting on those dunes with the moon reflecting off the lake and the anticipation of being able to witness a rare event in nature making it all worthwhile. This night was truly was an incredible experience that I hope I get to enjoy again some day and thanks mom, kayak camp finally paid off!

Lauren’s Low: Leaky waders means wet feet and heavy boots. Yes, my waders got a hole this week – right where the boot meets the pant. Every time I was in water passed my shins my leg got cold marsh-water wet, my socks got squishy, and my boot filled with water making me trudge like a swamp monster even more gracefully than I already do. Arts and crafts is in my near future to repair this hole, but until then, squishy socks it is.