Ophidiomyces

True fungal pathogens have been increasingly associated with free-ranging wildlife epidemics. Two recently studied examples include the effects of chytridriomycosis, caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, on global frog populations and the asexual ascomycete, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, causing white-nose syndrome in North American bat populations. One of the latest emerging fungal pathogens of vertebrate animal populations, Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola, was first observed in 2006 affecting populations of pitvipers in the eastern United States, and later confirmed in Eastern Massasaugas (Sistrurus catenatus) from Illinois in 2008. With the current rate of decline in global biodiversity, it is apparent that wildlife diseases similar to those described above are serving as threats to population declines potentially resulting in species extinctions.

Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola is currently placed in the order Onygenales (Ascomycota) within the family Onygenaceae. This fungus is closely related to other species of Onygenaceae within the Chrysosporium anamorph Nannizziopsis vriesii (CANV) complex that causes dermal lesions in reptiles.16 The genus Ophidiomyces currently contains only one species, O. ophiodiicola, and it is known to infect only snakes leading to the syndrome Snake Fungal Disease (SFD) which causes widespread morbidity and mortality across the eastern United States.

Historically, several case reports of skin disease in snakes were confirmed or suspected to be CANV or CANV-like. However, since publication of the description of the genus Ophidiomyces in 2013 and with the use of advanced molecular techniques, it is now thought that many of these infections may have been caused by O. ophiodiicola. An outbreak of fungal mycosis with clinical signs consistent with SFD was seen in pigmy rattlesnakes (S. miliarius) in Florida in the early 2000’s, but neither Ophidiomyces nor CANV were identified in that case.7 This outbreak included 42 pigmy rattlesnakes, one garter snake (Thamnophis sp.), and a ribbon snake (Thamnophis sauritus) within a 2 yr period, and retrospectively the authors identified an additional 59 pigmy rattlesnakes with signs consistent with mycotic disease.7 While these were not confirmed to be SFD at that time, it highlights the need to utilize advanced molecular techniques for accurate identification of the etiological agent during mycotic outbreaks.

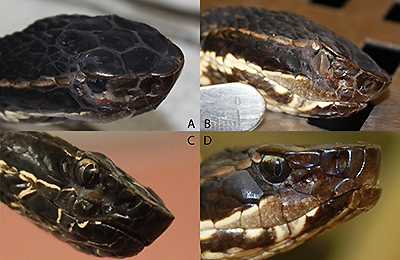

Since 2008, Eastern Massasaugas from the Carlyle Lake population in Illinois have been diagnosed with SFD. Free-range infected massasaugas display skin lesions, which vary from pustules or nodules to severe swelling of the skin. Infections in this species have been known to invade deep muscle tissue and infect muscle and bone. Prior to 2014, lesions were thought to only affect the head and neck of snakes, but lesions have now been observed in the skin of the entire body in massasaugas in Michigan. In 2006, a population of timber rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) in New Hampshire was observed with lesions on the head, neck, and body consistent with SFD. The authors hypothesized that environmental conditions (increased rainfall) were likely the explanation for the increased prevalence and/or severity as no other lesions were noted in their follow-up study in 2009. To date, all reports related to pitvipers have been consistently associated with dermatitis.

While infections h ave been observed with great frequency in pitvipers, there are numerous reports of CANV or SFD in nonvenomous colubrid snakes. The manifestation of SFD in North American colubrids snakes is variable and has included pneumonia, ocular infections, and subcutaneous nodules. A case of O. ophiodiicola was observed in a captive black rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta) with a subcutaneous nodule. In addition, mycosis was observed in the skin as well as a more systemic invasion involving the lungs and eye (one case) and lungs and liver (one case) of garter snakes

ave been observed with great frequency in pitvipers, there are numerous reports of CANV or SFD in nonvenomous colubrid snakes. The manifestation of SFD in North American colubrids snakes is variable and has included pneumonia, ocular infections, and subcutaneous nodules. A case of O. ophiodiicola was observed in a captive black rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta) with a subcutaneous nodule. In addition, mycosis was observed in the skin as well as a more systemic invasion involving the lungs and eye (one case) and lungs and liver (one case) of garter snakes

While the presence of the fungus causing infections in individuals is concerning, the role that it might play in population declines is more alarming. A timber rattlesnake population in New Hampshire consisted of 40 individuals pre- SFD; however, by the conclusion of that particular study, the entire population was reduced to 19 individuals. While many factors are affecting the conservation of this population, the occurrence of this pathogen may serve as an additional threat to its conservation.

Snake Fungal Disease Publications

Allender, M.C., M.J. Dreslik, S. Wylie, C.A. Phillips, D. Wylie, M.A. Delaney, M. Kinsel. 2011. An Unusual Mortality Event Associated with Chrysosporium in the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus). Emerging Infectious Diseases 17:2383-2384.

Allender, M.C., M.J. Dreslik,, D.B. Wylie, S.J. Wylie, J.W. Scott, C.A. Phillips. 2013. Ongoing Health Assessment and Prevalence of Chrysosporium in the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus). Copiea 2013:97-102.

Dolinski, A.C., M.C. Allender, V. Hsiao, C.W. Maddox. 2014. Systemic Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola infection in a free-ranging Plains garter snake (Thamnophis radix). Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 24: 7-10.

Allender, M.C., D. Bunick, E. Dzhaman, L. Burrus, C. Maddox. 2015. Development and use of real-time polymerase chain reaction assay for detection of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola in snakes. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 27: 217-220.

Tetzlaff, S., M. Allender, M. Ravesi, J. Smith, B. Kingsbury. 2015. First report of snake fungal disease from Michigan, USA involving Massasaugas, Sistrurus catenatus (Rafinesque 1818). Herpetology Notes 8: 31-32.

Allender, M.C., D.B. Raudabaugh, F.H. Gleason, A.N. Miller. 2015. The natural history, ecology, and epidemiology of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola and its potential impact on free-ranging snake populations. Fungal Ecology 17:186-190.

Allender, M.C., R.E. Junge, S. Baker-Wylie, E.T. Hileman, L.J. Faust, C. Cray. 2015. Plasma electrophoretic profiles in the eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus) and influences of age, sex, year, location, and snake fungal disease. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 46:767-773.

Allender, M.C., S. Baker, D. Wylie, D. Loper, M.J. Dreslik, C.A. Phillips, C. Maddox, E.A. Driskell. 2015. Development of snake fungal disease after experimental challenge with Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola in cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorous). PLOS One 10: e0140193/ doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140193.

Allender, M.C., C.A. Phillips, S. Baker-Wylie, D.B. Wylie, A. Narotsky, M.J. Dreslik. 2016. Hematology in an Eastern massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus) population and the emergence of Ophidiomyces. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 52: 258-269.

Rzadkowska, M., M.C. Allender, M. O’Dell, C. Maddox. 2016. Evaluation of common disinfectants against Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola, the causative agent of snake fungal disease. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, DOI: 10.7589/2016-01-012.

Allender, M.C., E.T. Hileman, J. Moore, S. Tetzlaff. 2016. Detection of Ophidiomyces, the causative agent of snake fungal disease, in the Eastern Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus) in Michigan, USA, 2014. Journal of Wildlife Diseases, DOI: 10.7589/2015-12-333.

Barber, D.M., C.R. Sanchez, P. Roady, M.C. Allender. 2016. Snake fungal infection associated with Fusarium found in Nerodia erythrogaster transversa (Blotched water snake) in Texas, USA. Herpetological Review 47: 39—42.

Ravesi, M., S.J. Tetzlaff, M.C. Allender, B.A. Kingsbury. 2016. Detection of snake fungal disease from an eastern milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum) in northern Michigan. Northeastern Naturalist 23: N18-N21.