By Maddy Erba, VM17

To the Future Veterinary Students of the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine:

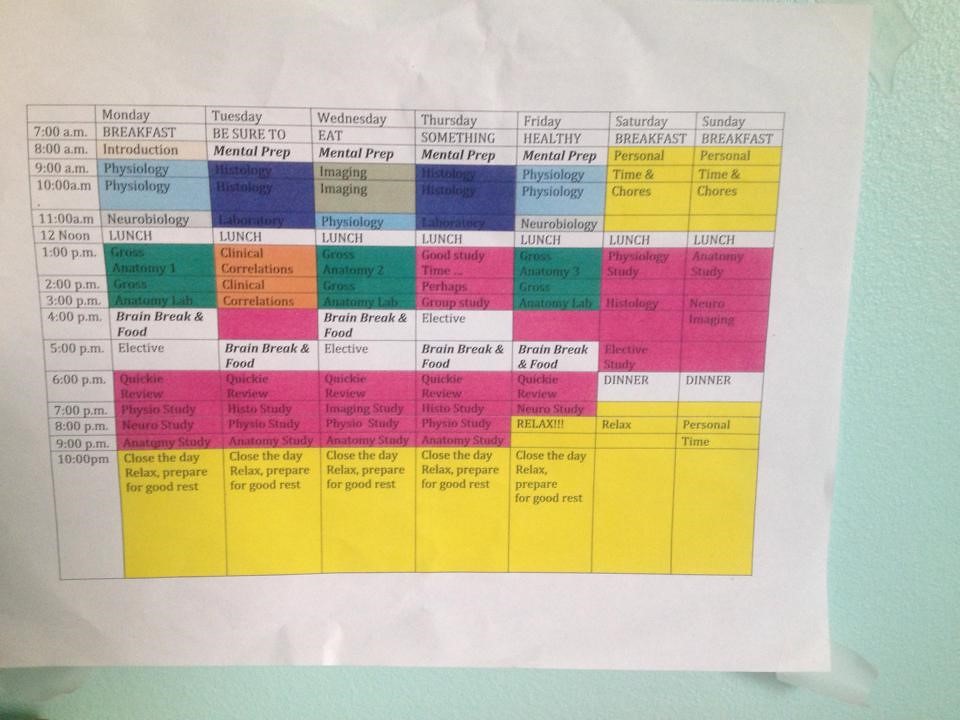

It was a hot day in the middle of orientation week when Dr. Foreman explained the benefits (and setbacks) of joining clubs. It had been several long days of sitting in the classroom, listening to information about my new academic life and wishing I could go outside for a bike ride. Dr. Foreman was cautioning us about joining extracurricular clubs, especially the Wildlife Medical Clinic (WMC) which is operated by volunteer veterinary students under faculty guidance and mentorship. Dr. Foreman listed the many reasons why we should think twice about joining the WMC. He explained that to be a member you needed to go to rounds, meetings, treatments, be on a pager shift, and care for orphans. I recall the phrase “time suck” being used multiple times. The administration gave us a schedule at the beginning of first year, which I have supplied for you. If you look closely there isn’t even time to eat dinner let alone find all this magical non-existent time in the week for the wildlife clinic.

Being new to Illinois and unfamiliar with the curriculum, I heeded Dr. Forman’s advice. However, that didn’t stop me from going to the club fair and listening to the forbidden fruit of WMC. There Jenny Kuhn stood with a great horned owl perched on her arm, Nokomis. She told me the wonderful benefits of joining – how we can practice physical exams, learn to write SOAPS, practice communicating within a team, and care for a variety of species. And those are just a few of the perks. Yes, WMC is a time commitment, but it also solidifies what we learn in veterinary school.

After careful consideration, I decided to join. We were told we could leave at any time if school became too challenging, or if we decided wildlife medicine wasn’t for us. However, as long as we were members, we were expected to do all the work, go to the meetings, and be a team. On my team were five amazing team leaders – Stephanie Zec, Erica Morton, Teresa Schecker, Laure Monitor, and Amanda Kuhl. This group of experienced individuals taught me everything I know about wildlife medicine. We practiced wing wraps, how to calculate medications, how to make a splint. I learned how to put in an interosseous catheter on raptor! I practiced communication skills, something everyone can improve upon. I was applying concepts from school, asking intelligent questions, and learning by doing! By the end of my first year I had gained an enormous amount of self-confidence.

On May 1st 2014, just sixteen days before the end of the semester, I appreciated the fact that I was laying the foundation to be a skilled veterinarian. I was nervous because an undergraduate student and I were the only two people on PM treatments. I was nervous because as the veterinary student, I was in charge, and I don’t normally like taking the lead. Our patients at the time were an opossum with a distal tail amputation, an orphaned squirrel with a maxillary swelling, and an orphaned squirrel with lung crackles that we thought were from aspirating food during a feeding.

We decided to feed the two orphaned squirrels first, because we thought they would be the less challenging patients. We examined the squirrel with the swelling first, and fed him. He looked alright.

It was time to feed the second squirrel. She suckled roughly two thirds of her meal, and then started shaking. We quickly re-heated a rice sock to keep her warm as she ate dinner, and she seemed to be okay after that. But when I auscultated her heart and lungs, I knew there was a problem. The crackles in the left lung field were still present, but the more alarming observation was her heart. Normally you should not be able to count the number of heart beats per minute on a squirrel. I counted about 120 bpm. Normally the heart makes a “lub-dub” sound, but on our squirrel you could only hear the “lub” and the heart sounded like it was struggling to pump blood throughout the body. We also noted a sinus arrhythmia (which may be normal in young animals) but is still worth noting.

What do we do? We call in help from our team leaders. We rallied the troops. It is never wrong to ask for help or clarification. Amanda confirmed our observations. We determined that our furry friend was not dehydrated, and therefore did not need fluids to increase her cardiac output. So we took radiographs, which revealed an enlarged heart. This young animal had signs of a cardiomyopathy, or abnormality in her heart. It is possible that this was a congenital anomaly that had been present all along but became apparent as time went on. It was only through this valuable clinical experience that I was able to appreciate the signs of a problem in this squirrel and apply my classroom knowledge to a real case scenario.

Congratulations on making it into veterinary school. Part of being in a professional graduate program is being able to think critically, and to think for yourself. The Wildlife Medical Clinic provides you with the opportunity to learn from more experienced students. You won’t always have all the answers in vet school, but you should never feel afraid to ask for help. School is what you make of it. Your education is up to you. Learning by doing is not only enriching, it solidifies understanding of classwork. I strongly implore you to consider Wildlife Medical Clinic, take a chance, save a life, and strengthen your veterinary education.