By Cassie Lynch, C/O 2023

As winter approaches, many local species prepare for the colder temperatures by relocating, growing a thicker fur coat, and even hibernating. We often think of birds, foxes, and bears as species that make these alterations to survive the cold. Less frequently discussed are the cold weather adaptations of reptiles and amphibians, who seem to magically reappear as the warmer temperatures return. One species in particular battles the freezing temperatures by allowing up to 65% of its total body water to freeze. What is this magical creature you say? It is none less than the wood frog (Lithobates sylvatius) native to the northern half of Northern America.

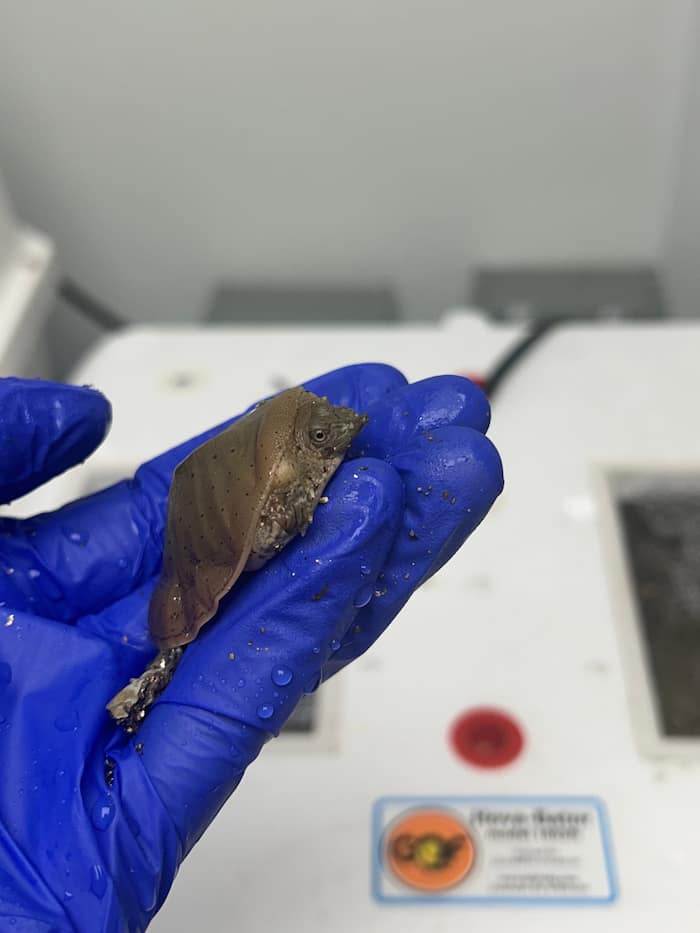

In Illinois, the wood frog is found in the woodlands of our northeastern, northwestern, and southern borders. It averages from 1.25 to 2.75 inches in length, which is roughly the diameter of a soda can. The wood frog is identifiable by the reddish-brown coloring of its back contrasting the lighter tan color of its belly. The dark mask on each side of its head just below and behind the eye is distinguishable feature, as are the red-brown stripes found on both sides of the body.

During the winter months, wood frogs enter a state called brumation, which is the amphibian and reptile version of hibernation. During this time, they enter a sleep like state with a decreased metabolic rate and therefore decreased need for energy. Just before brumation begins, wood frogs burrow a small hole in the ground, which allows them to stay close to the surface of the soil. This separates wood frogs from other amphibian species, most of whom must burrow below the freeze line to survive the winter.

To tolerate the freezing temperatures of Illinois winter, wood frogs naturally produce a high concentration of glucose, which acts as an antifreeze-like substance, to block the formation of ice crystals. This prevents the frogs from freezing completely, allowing them to survive the winter partially frozen. A higher concentration of the antifreeze substance is found in specific organs of the body to maintain proper metabolic function throughout brumation. This freezing adaptation is so extreme that, during the coldest months, this species will stop breathing and its heart stop beating! As the weather warms, the frog will thaw, and all organs will return to normal function.

Integrating a species’ natural history in its care plan is an important part of what we do in the Wildlife Medical Clinic. While we don’t often see wood frogs as patients, we are proud to be ready to care for any native amphibian that may need our help! Unfortunately, much of the natural habitat for the wood frog has been destroyed, and this species is listed as a Species in Greatest Need of Conservation in the Illinois Wildlife Action Plan. Efforts are being made by the Chicago Academy of Sciences and the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum to restore the wood frog population and its’ habitat. Hopefully through their efforts, wood frog populations in Illinois can rebound and these natural frog-cicles can continue to positively impact our local ecosystem!