Kaylee Cox & Natalie Zimmerman c/o 2022)

This February, a 30-pound male bobcat presented to the Wildlife Medical Clinic after a long journey from western Illinois. He was found on the side of the road by Illinois DNR who brought him to a local veterinarian (and former WMC volunteer!) who was able to stabilize the bobcat and begin diagnostics to assess the patient. There, radiographs revealed that this bobcat had pelvic fractures, likely from being hit by a car, as well as several bullet fragments throughout its abdomen. Because this veterinarian is a former WMC volunteer, she knew exactly who to call for continued care – our very own veterinary staff here at the Wildlife Medical Clinic! After the arrangements were made, this bobcat’s three-hour journey across Illinois began.

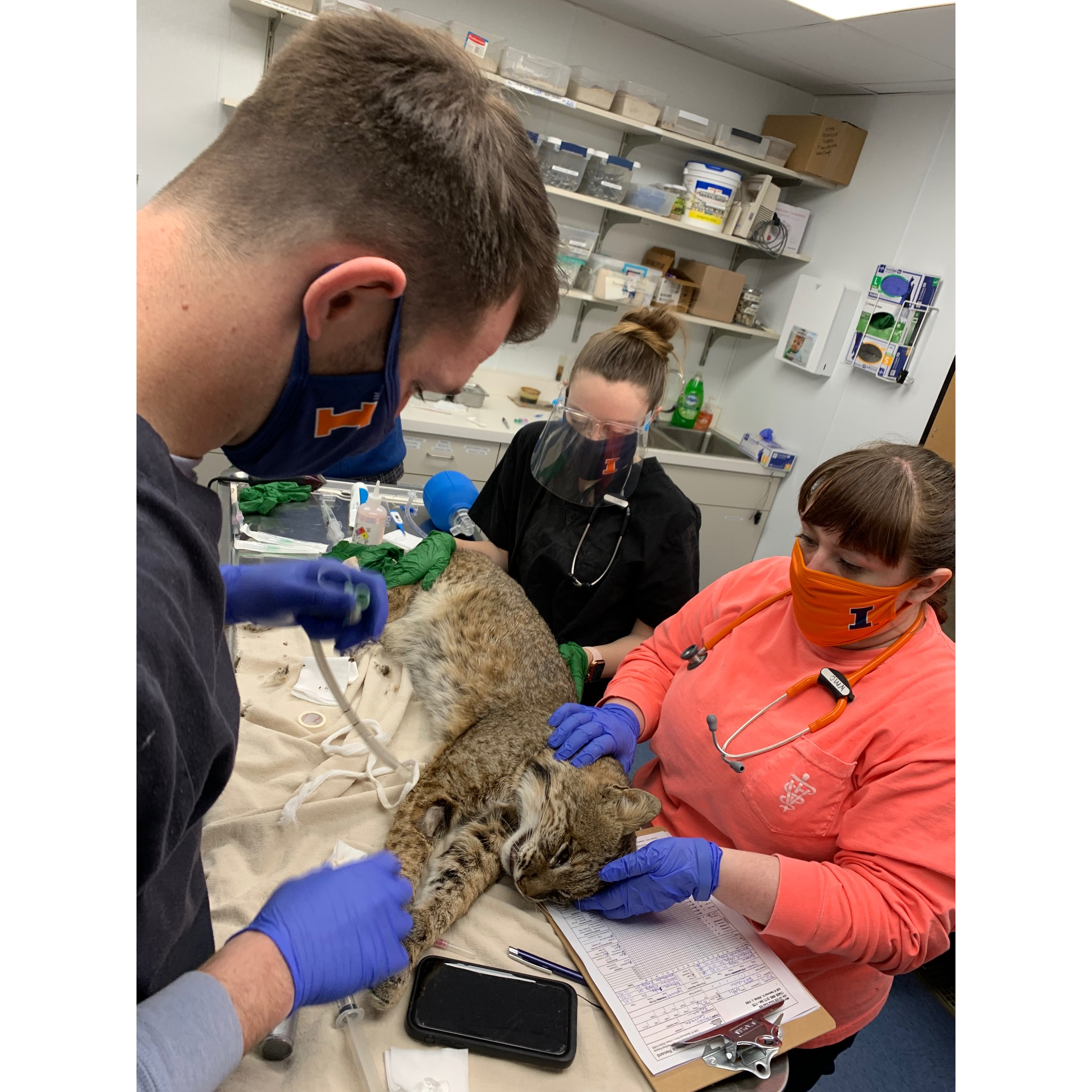

Upon arrival to the WMC, the bobcat was observed in his carrier for a “hands off” exam. By doing this, students and clinicians could see how the animal moved on his hind limbs after such a traumatic event. Students noted the animal had trouble standing and putting his weight on his back legs, giving further evidence that the pelvis had suffered severe injuries. With the guidance of one of our faculty mentors, Dr. Spencer Kehoe, students safely administered sedation to facilitate a further evaluation. Throughout this bobcat’s entire journey and stay at WMC, safety of both the cat and students/faculty was a priority. There were extensive discussions about recovery and physical therapy in order to find the most efficient and safe way to handle a large carnivore like this.

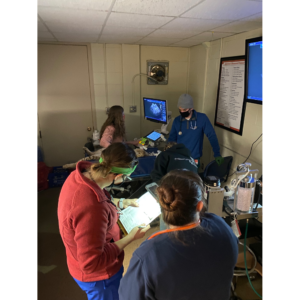

Once properly sedated, the bobcat was removed from the crate and had a full physical exam, from nose to tail, for any other injuries or signs of trauma. Apart from a few superficial wounds on his hind feet, no other evidence of trauma was noted during the exam. Under the supervision of Dr. Kehoe, several students were able to practice skills such as placing an IV catheter, monitoring anesthesia, wound care, and safe handling practices of a large carnivore. After the exam had been completed and all injuries noted, the bobcat was placed back into the carrier to slowly and safely wake up from the sedation medications, all while being monitored by the intake team. Food, water, and medications were provided to make the bobcat as comfortable as possible overnight.

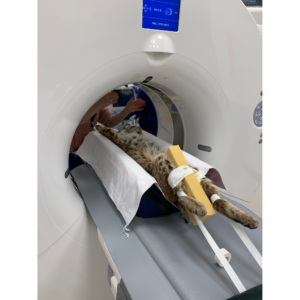

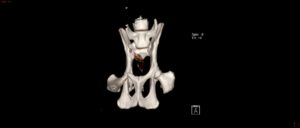

The next day, our diagnostic investigation began! With the help of magnanimous donors, the clinic was able to provide this patient with a CT scan. The CT scan allowed clinicians and students to see the true extent of the damage that had been done to the pelvis and the scan revealed that there were actually multiple pelvic fractures present. A 3D reconstruction of the pelvis was also created in order to help plan for a surgery to repair the fractures. We worked with Dr. Tisha Harper from the Small Animal Orthopedic Surgery and Dr. Stephanie Keating from the Anesthesia services at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital to determine that, with their help, the fractures were repairable with an optimistic return to full function! Bloodwork was also ordered to make sure the patient would be healthy enough to undergo surgery. This is a step that is commonly taken with veterinary patients. Bloodwork allows doctors to evaluate vital organs such as liver and kidneys. These organs are often the main players in how medications and anesthetics are metabolized throughout and removed from the body. Making sure these organs will be able to handle this important task is key to the success of any surgery (human or animal!).

Sadly, this is where the story takes a turn for the worse. The bobcat’s bloodwork showed signs of severe systemic illness that were not appreciable during our initial exam. The bloodwork documented a non-regenerative anemia, which is a concerning blood disorder and likely was already affecting this animal before his injuries. That sample also showed evidence of liver compromise and suggested a possible ruptured gallbladder. We consulted with Dr. Caroline Tonozzi from the Emergency and Critical Care service to determine the feasibility of a blood transfusion for our patient and opportunities to best aid in his critical needs. These findings also warranted yet another trip to the Radiology Service at the Veterinary Teaching Hospital for further investigation, as our newest findings could adversely affect the possible outcome of surgery and healing post-operatively. One of our radiologists, Dr. Audrey Billhymer,

performed an abdominal ultrasound to visualize the internal organs. She showed us evidence of fluid in the abdomen and described how to best evaluate patients with ultrasound after traumatic injury. While the gallbladder looked intact at the time of the scan, there was fluid around it suggesting its integrity had been compromised. Dr. Billhymer helped us to collect a sample of the abnormal fluid, which was then evaluated by our own Clinical Pathology Service. Unfortunately, bacteria and blood were found in the sample, consistent with our biggest fears. The bacteria indicated that this bobcat had a septic abdomen, a severe infection of the abdomen that had a significant negative impact on the overall prognosis of his case. With all of the new evidence and due to all of the factors at play: a broken pelvis, blood disorder, septic abdomen, and concerns regarding this patient’s ability to tolerate the aggressive and regular handling needed to manage his many problems, we made the difficult call to euthanize our patient.

The decision to euthanize is not easy and is never made lightly in veterinary medicine. Every veterinarian takes an oath to “first and foremost, do no harm” and this oath rang true in this case. For our bobcat, we would have needed to have an adult wild animal undergo up to three major surgeries to correct the pelvic fractures, alongside aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy to cleanse the abdomen of infection, a blood transfusion, and yet more diagnostics and treatment for his blood disorder. Similarly, the postoperative recovery period would have been incredibly difficult and the amount of stress it would put on the patient being under human care for such a long amount of time would have been considerably high. For surgical success, the bobcat would have had to be contained to cage rest for weeks before gradually increasing his space and ability to walk, then run, then jump over a period of weeks to months. In the end, we decided pursuing his case further was not fair, especially considering the high risk of complications that could arise. As veterinarians, we must advocate for our patient’s quality of life and sometimes that means making the difficult decision to end their suffering rather than inflict more pain in the hopes that a risky course of treatment will work. We simply could not ask this animal to go through so much, especially knowing his prognosis for release was poor even if we were to pursue all interventions successfully.

stress it would put on the patient being under human care for such a long amount of time would have been considerably high. For surgical success, the bobcat would have had to be contained to cage rest for weeks before gradually increasing his space and ability to walk, then run, then jump over a period of weeks to months. In the end, we decided pursuing his case further was not fair, especially considering the high risk of complications that could arise. As veterinarians, we must advocate for our patient’s quality of life and sometimes that means making the difficult decision to end their suffering rather than inflict more pain in the hopes that a risky course of treatment will work. We simply could not ask this animal to go through so much, especially knowing his prognosis for release was poor even if we were to pursue all interventions successfully.

While the outcome in this case was not what we had hoped for, this case gave our students the opportunity to work with a species that we do not commonly see at WMC, practice hands-on skills, as well as critical clinical reasoning, and judgement. This case also taught our students valuable lessons in ethical veterinary care and interpersonal relationships. This bobcat’s care was a collaboration from multiple clinicians and services at the University of Illinois Veterinary Teaching Hospital, and allowed our students to synergize the knowledge of multiple specialties in the care of this animal. This bobcat has made an impact on many people and has made each of them a better doctor because of it. As always, difficult cases like this one help us to gain a deeper respect for our wildlife and the important role they play in the maintenance of our ecosystem. The Wildlife Medical Clinic will continue to provide the best possible care for our patients and always strive to advocate for their best interest.