North American Wetlands

North American wetlands are a sight to behold, with their crystal water reflecting the sun’s rays and the vibrant fish swimming beneath. The woven nests of pied-billed grebes, adorned with the leaves of lush cattails, deep blue wild iris, and brilliant yellow marsh marigolds, add to the beauty of these water-dominated landscapes. Despite their poor, oxygen-starved soils and highly variable conditions, these incredible ecosystems support more than 40% of the world’s biodiversity. Embark on a journey to explore the wetlands of North America, from the saltwater mangroves of the Gulf Coast to the interdunal wetlands of the Door Peninsula and witness the unique bird species that depend on them.

Gulf Coast Mangroves

We begin amongst the mangroves of the Gulf Coast. A mangrove is one of many species of trees specially adapted to live within coastal intertidal zones, the area between the lowest and highest tides. The intertidal zone can be covered in freshwater, saltwater, or a mix at any time. It can also be ten or more feet deep or completely dry, sometimes even on the same day. These drastic changes mean the mangroves provide stable shelter to numerous species wishing to call the coastal intertidal zone home.

One such species, the roseate spoonbill (Platalea ajaja), can be found along the coasts of Florida and Louisiana in the United States. Its range once stretched along the entire gulf but was decimated by feather hunters in the early 1900s. It has stunning plumage, with a bright pink body, brilliant red along its wings, and an orange tail. Its most striking feature, and the reason for its name, is its spoon-shaped bill. This bill allows it to feed via “tactolocation,” where it slowly walks through the water, swinging its head back and forth, mouth open until it feels its favorite food (typically small fish or invertebrates) and snatches it out of the water. Essential locations protect many roseate spoonbill breeding sites, including Everglades National Park, the Kennedy Space Center, and the Merritt I National Wildlife Refuge. However, coastal development remains a significant threat as the spoonbills must forage beyond their nesting sites. This can be seen in the Florida Keys, where large developments have removed the mangroves and physically pushed the spoonbills to forage in new locations. Coastal development has also directly resulted in decreased water quality that impacts the fish and invertebrates on which the spoonbills depend. It’s crucial to recognize the importance of conserving fragile mangrove habitats to safeguard diverse and unique species like the roseate spoonbill for the benefit of future generations.

Cache River Wetlands

Next, we will stop within the Cache River Wetlands, one of 41 North American sites recognized as internationally important by the International Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar). This area supports a network of cypress-tupelo swamps. These beautiful ecosystems bring alligators and mosquitos to mind rather than the corn and soybeans one typically pictures when thinking of Illinois.

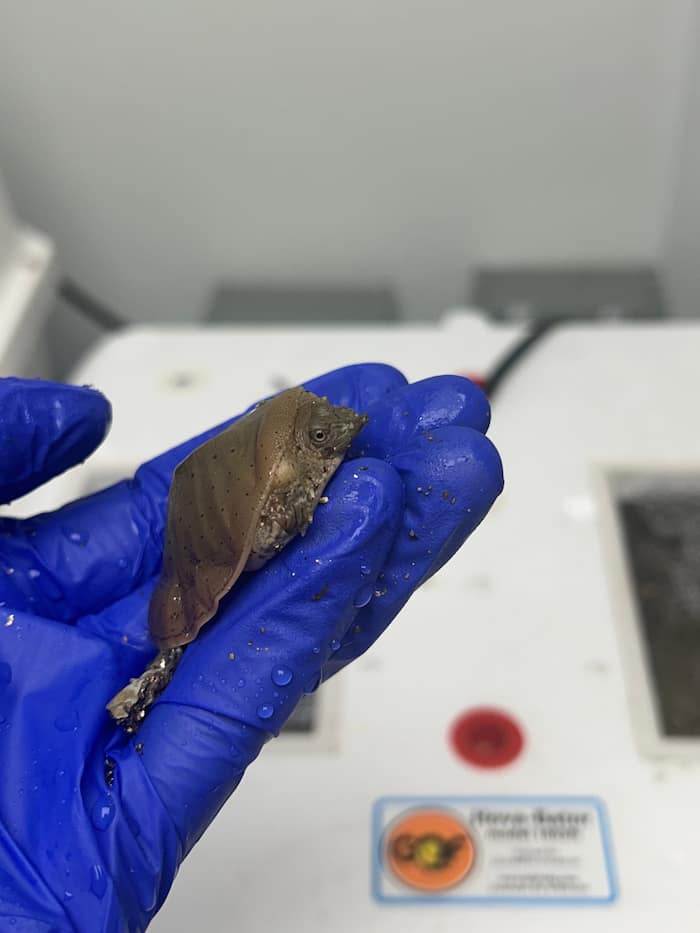

Along the edges of these swamps, where murky water gives way to rich, damp, worm-filled soils, lives one of North America’s strangest birds: the American woodcock (Scolopax minor). A member of the sandpiper family, this bird frequents swamp edges, damp forests, and other locations with soft soils perfect for digging up their favorite food: earthworms. Their long, think beaks pierce through the soil, probing for worms. Their tilted eyes, located so far back on their head that they are behind their ears, allow them to see the sky even when their beak is buried in the ground. Adding to their uniqueness is their buzzing call, described as “bzeep”, which can be heard emanating from the darkness of night as they perform their courtship rituals. All these traits have spurred the creation of a colorful host of names, including bog sucker, night partridge, and timberdoodle.

Great Lakes

Farther north, we can find the Great Lakes, one of Earth’s most incredible freshwater ecosystems. These lakes make up 1/5 of Earth’s freshwater and hold more than six quadrillion gallons. Tucked along the western edge of Lake Michigan sits the coastal wetlands of the Door Peninsula, another Ramsar recognized location. These wetlands, called interdunal wetlands or dune slacks, are some of the most unique wetlands in the world. Coastal dune systems are shifting ecosystems defined by the movements of wind and water. Interdunal wetlands are created when strong coastal winds carve out sand to a point below the water table, allowing water to well up to the surface. Much like the dunes that surround them, interdunal wetlands change from day to day, decade to decade, and century to century as the dunes cover them, only to reveal them again in the future.

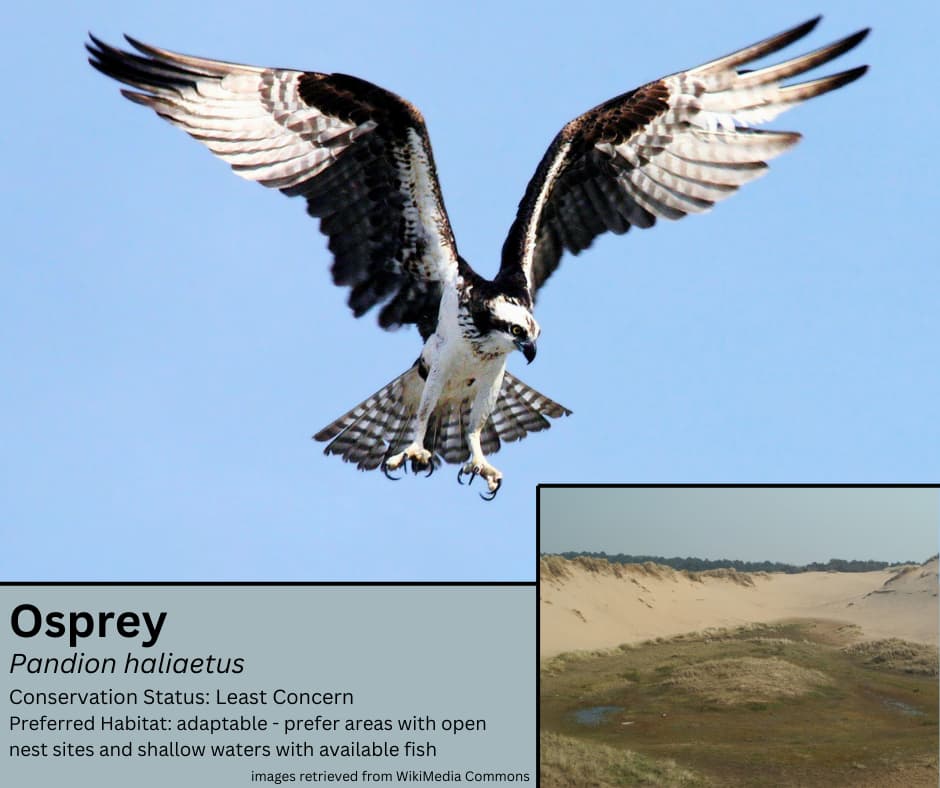

This pristine ecosystem provides the perfect habitat for the osprey, a widely admired raptor whose diet consists mainly of fish. Osprey populations rapidly declined from the 1950s through the 1970s due to the widespread use of the chemical pesticide DDT, which caused the thinning and weakening of bird eggshells. Studies of osprey provided the crucial evidence needed to enact bans against DDT, allowing bird populations across the country to begin to recover. More recently, habitat and nesting-site loss have impeded the osprey’s recovery, but the increasing popularity of artificial nesting platforms and the osprey’s preference for these platforms over other natural sites has allowed them to thrive once again.

Conserve Wetlands

From the mangroves of the Gulf Coast to the cypress-tupelo swamps of the Cache River Wetlands and the interdunal wetlands of the Door Peninsula, North America’s wetlands offer a diverse array of habitats for unique bird species. These wetlands not only provide a home for these remarkable bird species but also contribute to the rich biodiversity of North America’s landscapes, making their conservation imperative for generations to come.

Written By: Tyson, Senior Manager and Class of 2026.