West Nile virus is an arthropod-vectored virus that was first identified in New York in 1999. Wild birds serve as the natural reservoir for the virus, with some species being more susceptible to disease than others.

The appearance of West Nile virus in Illinois occurred in 2001, with both birds and people becoming sick in the Chicago area. August 2002 brought the first central Illinois cases to local hospitals, as well as to the Wildlife Medical Clinic. Corvids, crows, and jays were known to be exquisitely sensitive to the virus, with many of these birds succumbing to the infection rapidly. However, some species of birds seemed resistant to the viremia, while others developed clinical signs but were able to recover.

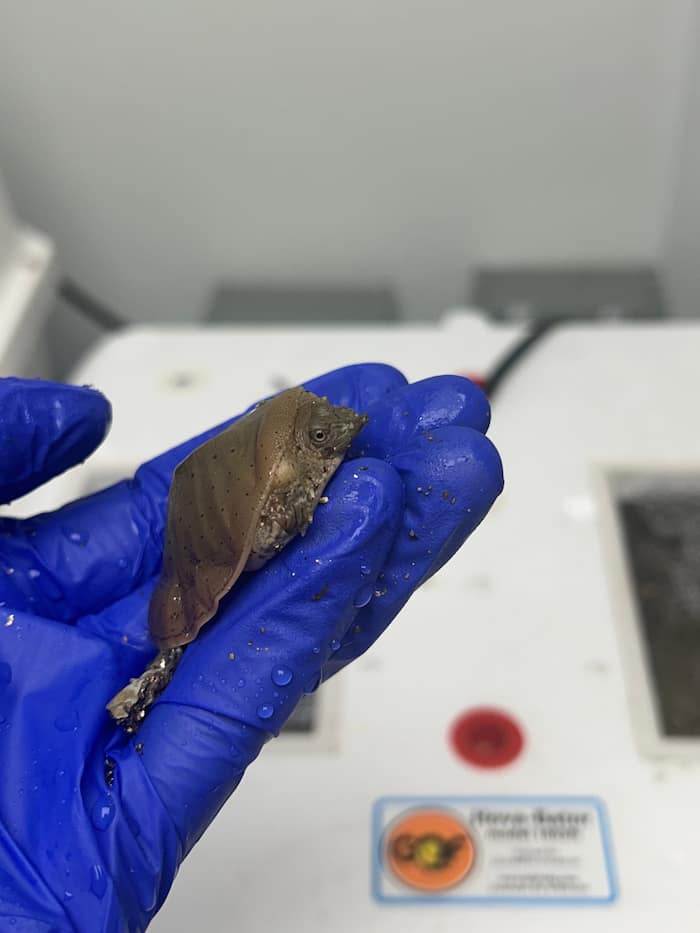

Since 2002, the Wildlife Medical Clinic has seen numerous cases of confirmed and suspected West Nile virus infection. Most of the time, infected birds display signs of neurologic disease including inability to fly, head tilt, unsteady gait, and lethargy. These birds also have evidence that they are fighting systemic inflammation when evaluated through diagnostic tests. Some birds with West Nile virus infection also develop ocular disease with varying degrees of vision impairment. The only treatment for the virus is supportive nursing care to try to help the animal pull through, but the virus is very serious and can be fatal.

Although newspapers have slowed their reporting of West Nile, it is still very much present in our state and impacting wild bird populations. The Wildlife Medical Clinic has seen several suspected West Nile Virus cases this year. Many have been confirmed by the Veterinary Diagnostic Lab at the University of Illinois.

West Nile virus is spread by mosquitoes that have bitten infected animals or people. In humans, most healthy people do not show signs of illness. As the virus has become endemic, or established over time, both human and animal populations have developed a degree of immunity against the virus through previous exposure. This probable immunity has resulted in fewer clinical cases being reported annually as compared to when the virus emerged. However, local public health departments across Illinois still perform mosquito control and disease monitoring by submitting birds that have been found deceased to the Diagnostic Lab for testing. You can protect yourself from West Nile Virus by avoiding mosquito bites: stay indoors when mosquitoes are most active (at dusk), use mosquito repellent, and wear long sleeves and pants. Keep areas where water pools drained to prevent mosquito larvae from hatching.

If you see a bird on the ground in the same place for many hours, consider bringing it to the Wildlife Medical Clinic for care. A towel can be placed over the bird to calm the bird and help control the wings. The animal can then be scooped into a box for transport. Be careful and consider wearing a pair of thick garden gloves and a long sleeved sweatshirt to protect yourself against the beak and talons of large raptors. The animal will be accepted 24/7 at the Small Animal Clinic of the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine in Urbana.

—Erin Newman, 4th-year veterinary student