Here at the Wildlife Medical Clinic, we take digital radiographs, or x-rays, when we want to examine patients of all species and sizes. Radiographs are images of the body used to evaluate internal structures like organs and bones. When injured turtles or other chelonians come to us after encountering a car, lawn mower, dog, or an unknown attacker, we often take radiographs. This helps us to better visualize the carapace (the top portion of their shell), plastron (the bottom portion of their shell), and survey for any internal injuries. This will give us a better idea of that we need to do to optimize treatments for that particular patient.

The standard radiograph views for any turtle are dorsoventral (top to bottom), lateral (side to side), and craniocaudal (front to back). One thing to note with turtle radiographs is that we try to avoid rotating the turtle on its side. By rotating them on their side, we shift the organs in their body, altering the value of the radiographs and potentially causing harm. When we take radiographs, we also may need to have our turtle patients be sedated or under general anesthesia. This is so we can properly position their head and limbs to get an image that is diagnostic without causing the patient undue stress.

When looking at the craniocaudal view of a turtle, we can evaluate the lung fields, stomach, and many bones, including the cranium, scapula, coracoid, humerus, pelvis, and femur. We can also examine the cranial opening of the carapace, which is where the turtles head is located, or the caudal opening of the carapace, which is where the turtle’s tail is located. For this view, the turtle remains on its ventral surface (belly), and we are positioning the radiograph to view the turtle in the direction of the head to the tail.

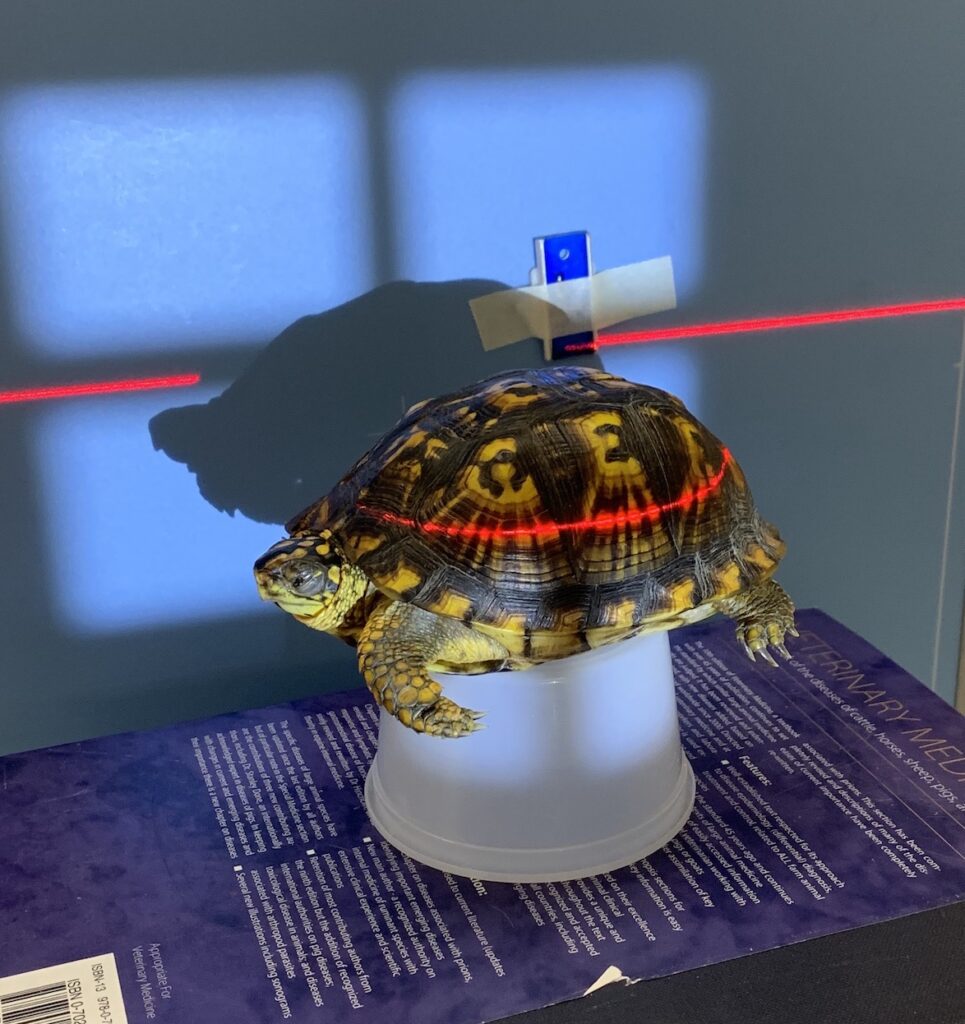

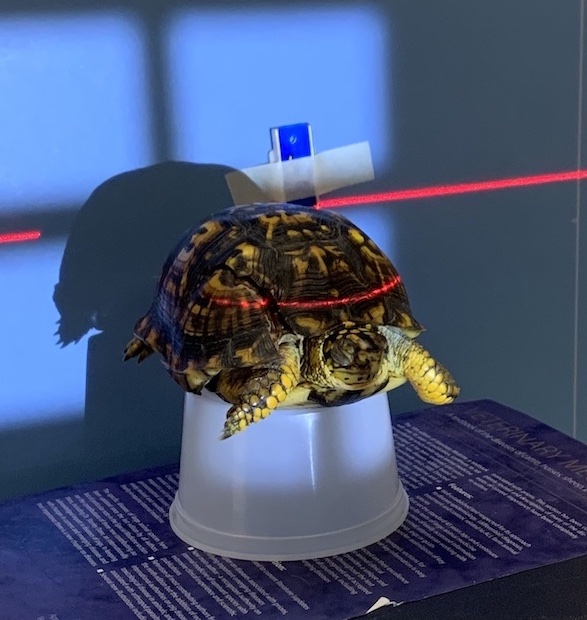

When we look at a lateral view, we are looking at the side of the turtle. Typically for this view, we will place the turtle on a plastic cup or container to elevate the patient. This way, their front and hind limbs can be extended under their shell which makes it easier to examine their legs on radiography. In this view, we typically examine bones, including the cranium, mandible, spine, scapula, coracoid, humerus, femur, pelvis, fibula, and tibia. We can also evaluate internal organs, including the trachea, lungs, liver, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. This view can also be used to screen for eggs in the turtle’s reproductive system.

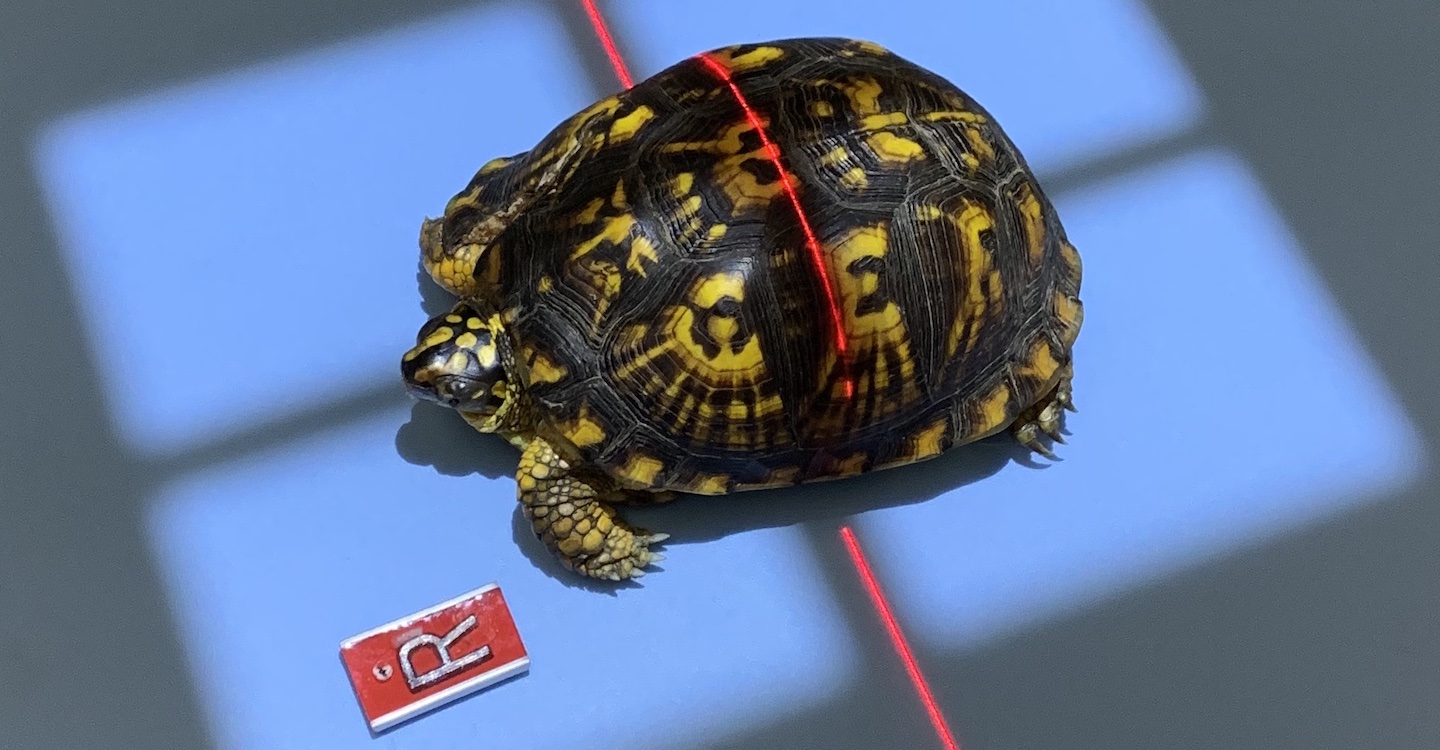

In the dorsoventral view, we can evaluate the cranium, spine, scapula, coracoid, humerus, radius, ulna, pelvis, femur, fibula, and tibia. In this view, the image is taken from the top of the shell to the bottom while the turtle is on their ventral surface. The bones of the plastron can also be visualized in this view, which are the epiplastron, entoplastron, hypoplastron, hyoplastron, and xiphiplastron.

It is important to take images from all three positions of a turtle to best assess our patient. Taken together, these images allow us to visualize multiple sides of the bone, tissue, or organ we want to examine more closely. After we take the radiographs, we make sure the patient is stable, and then move on to evaluating the images. The volunteer students at the Wildlife Medical Clinic work with our veterinarians to review normal anatomy and ensure any abnormalities are identified. Once the images have been evaluated, we use that information to formulate a treatment plan, and hopefully, help the turtle get back to the wild where it belongs.

Written by Chloe Dupleix, class of 2024.