Many of you have found an injured or orphaned animal and brought it to us, but do you know what happens after you drop it off? Come with us as we walk you through everything that happens when wildlife visits the Wildlife Medical Clinic here at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign!

When you bring an animal to the front desk, they send out a page to all the volunteers in the clinic. Countless phones throughout the college light up with “Wildlife Medical Clinic Receiving:” and the patient’s species, if known. The volunteer team assigned to triage that day then springs into action, heading to the clinic to bring the animal back and begin the triage process. It is very important that a detailed history is given on the animal’s intake sheet, as this helps the triage team determine appropriate steps going forward. Certain species that are susceptible to Canine Distemper Virus, such as raccoons, bobcats, and coyotes, should be left in your car until the triage team arrives to transport them, as the lobby is a shared space amongst many animals also susceptible to this disease. It is always worth calling prior to bringing in an animal for best practices and safety advice from our volunteers.

Once the animal has been taken back to the designated triage room within the clinic, volunteers begin with a hands-off exam. A lot of important information can be gained simply by looking at the animal before it has been touched by the volunteers. Is it standing? Are there any visible wounds? How does it react to the presence of humans? Even something as simple as how a patient is holding themselves can tell us where an injury may potentially be. Take the image of a white-tailed kite, a species found in California, Texas, and parts of Mexico. The way the kite is holding its wing slightly out and away from itself is called a “wing droop,” which can be indicative of an injury to the wing or the flight apparatus that physically supports the wing.

When the hands-off exam is complete, it is time for volunteers to restrain the patient for a physical exam. Proper restraint is important for the safety of both the volunteers and the patient. There are two types of restraint used: physical and chemical. Physical restraint is used for smaller patients and raptors and involves using specialized gloves that protect human hands from bites, scratches, and the vice-like grip of a raptor’s talons. All volunteers are trained in how to properly hold different species so that they cannot injure themselves or others. Chemical restraint, or the use of sedative medications, is used for carnivores, meso-omnivores, and other species that pose a more significant risk to volunteer safety when awake, as well as patients that are exhibiting signs of stress and would benefit from the anxiety-reducing effects the medications provide. A falconry hood is an alternative option that can be used in raptor patients. This leather mask completely covers the raptor’s eyes, keeping them calm and comfortable during what would otherwise be a very stressful time.

After the patient is properly restrained, the next step is to take vitals. Basic vitals include a heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature. These provide insight into the patient’s status, allowing the triage team to quickly make decisions. The goal of a triage exam is to stabilize the patient so that procedures and diagnostics (such as bloodwork or radiographs) can be performed in the future. Stability can change rapidly, but monitoring vitals gives the triage team the information they need to provide the medications and treatments that can improve stability and support the patient.

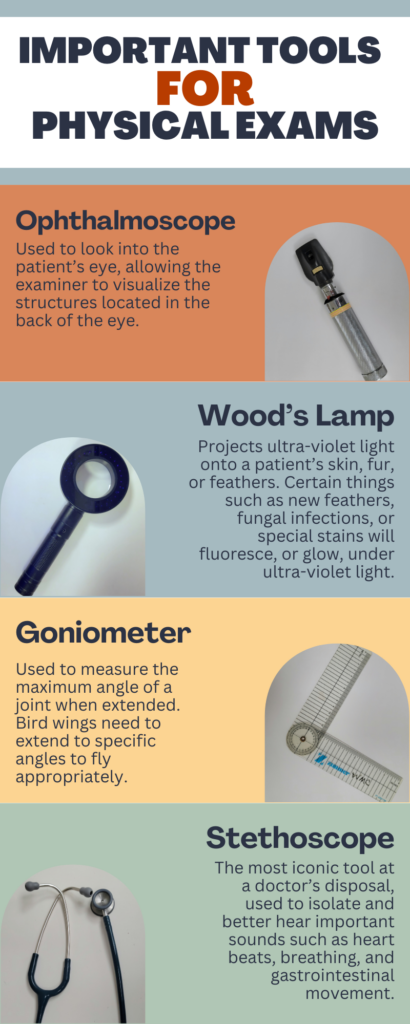

Now that vitals have been recorded, it is time for the physical exam. Every volunteer has a different approach they utilize to complete an exam, but every exam must involve careful observation of the presenting animal’s entire body. A good physical exam can prevent unneeded procedures, reducing the time an animal needs to be handled and thereby decreasing the animal’s overall stress. Examiners use a combination of sight, touch, smell, and hearing as well as various tools to gain a complete picture of the animal’s status.

The ultimate goal of wildlife rehabilitation is to release the animal back into the wild. For this to happen, the animal needs to truly function as a wild animal; they must be able to successfully find or catch food, move and maneuver in a typical way, demonstrate appropriate behaviors including fear of humans, and possess all of the physical characteristics they need to regulate themselves, among other standards. If the triage team determines that the animal will not be able to meet those standards, even after treatment and support, then the animal is recommended for euthanasia. The purpose of euthanasia is to end suffering, but wildlife practitioners have the unique dilemma of also determining the possibility of future suffering. Most of our wildlife patients are not going to return to the clinic when complications of their problems arise or worsen post-release. To release a wild animal knowing that it is at a disadvantage in the functions it needs to survive is to cause suffering. The triage team presents the case history, their exam findings, and their recommendation to a licensed veterinarian. The veterinarian then either approves the recommendation or offers advice on treatment options that may work.

If the problems the patient is experiencing are treatable, then the triage team gets to work providing supportive therapies. These often include fluid therapy (most wildlife patients present with some level of dehydration), anti-inflammatory and pain medications to keep injured patients comfortable, and other treatments more specific to the patient’s case.

Since we are a student run facility, we depend on you and the rest of our community to bring these patients to us when they need help. Without your support, we would not be able to do what we do. We hope you enjoyed this special look into our triage exam process and the work we do here at the Wildlife Medical Clinic.