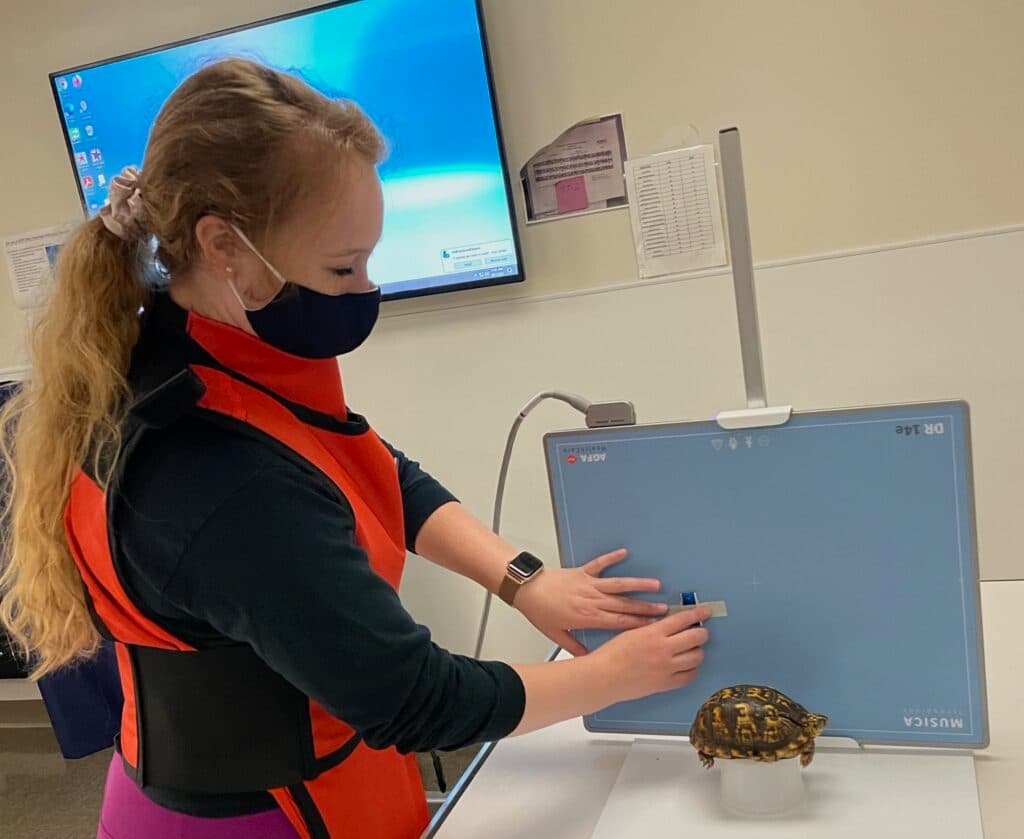

An adult female Eastern box turtle (Terrapene Carolina) was presented to the Wildlife Medical Clinic (WMC) in October for potential blindness. On exam, the turtle was found to have several abnormalities, including eyelids that were swollen shut, ocular discharge, swollen ears, nasal discharge, and wounds near the rear legs. She was started on a detailed treatment plan that consisted of anti-inflammatory and antibiotic medications, fluid support, and nebulization for suspected respiratory disease. In addition to a custom enclosure to support her needs, we also leveraged what waning warmth and sun was left of the season to stimulate her activity and appetite with supervised time outside whenever possible.

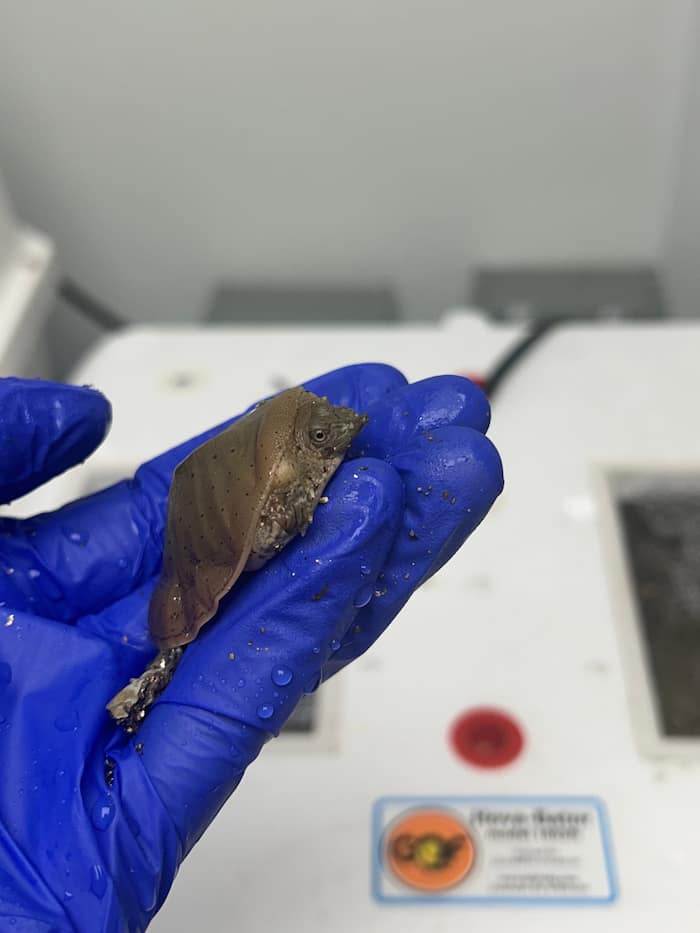

Despite our efforts, there was no appreciable improvement in this turtle’s signs, and she still was not eating after two weeks of care. Consultation with the Veterinary Teaching Hospital’s Ophthalmology service revealed inflammation of the cornea (eye surface) and iris (colored part of the eye). Thankfully, infectious disease testing at the College’s Wildlife Epidemiology Laboratory ruled out the most common and concerning infectious diseases which could be playing a role in this turtle’s illness. Taken together, we were highly suspicious of a vitamin A deficiency as the cause of this turtle’s signs. Our next phase of care included anesthesia to surgically place a feeding tube and a procedure to treat her swollen ears. With the feeding tube in place, we were finally able to provide the critical nutrients she needed to heal.

Turtles are notoriously slow to heal, and nutritional deficiencies are rarely a quick fix. After weeks of providing a nutrient rich diet via her feeding tube, nebulizing, soaking, and other treatments, we could finally say many of this turtle’s signs had improved! Unfortunately, by this time, we found ourselves well into the winter season. Wild turtles in Illinois brumate (hibernate) each winter, their bodies slowing down concurrent with the dropping outside temperatures. During this period, turtles can’t digest food the way they do in the warmer months. Turtles overwintering in the WMC will often brumate as they would in the wild, decreasing their activity and appetite as they wait for spring. Hoping to continue the healing process for this turtle, we attempted to “trick” her body into skipping brumation by providing light and temperatures that mimic summer conditions. Unfortunately, even in the WMC we can’t fight nature and our careful observations told us this turtle was showing signs of brumation despite our efforts. Knowing this turtle was no longer able to digest the food we provided through her feeding tube, we had to minimize her tube feeding so as not to cause the food to rot in her stomach as it sat undigested.

Over the next several months, some of this turtle’s signs re-presented, as she hadn’t yet fully healed her leg wounds and her vitamin levels were only starting to rebound when her body slowed down. We carefully balanced her medical care with her environmental needs, tweaking as needed to optimize her care and minimize handling and stress whenever possible. By mid-February, her leg wounds had fully resolved, her activity was increasing, and a blood sample showed her laboratory values were normal! It was finally safe to feed her again. We gave her a boost with injectable vitamins and slowly increased the food she received through the feeding tube. We are happy to report that, as of this writing, this turtle is now eating on her own and doing well! There will be several more weeks before the weather will be consistently warm enough to release her. We will continue to monitor her progress throughout that time and are optimistic she will one day roam free in the woods where she belongs.

Written by Ryan Patterson, class of 2023.