Emergency Medicine for People and Animals

I was a pretty clumsy kid growing up, often ending up in the emergency room for a variety of reasons. Broken bones, ruptured tendons, and I was even bitten by a cookie cutter shark at one point. Early on in my life, I had no desire to be a veterinarian. However, I have always had a deep love and fascination with animals. During my many times in the emergency room waiting area, I pondered, what is the emergency room like for animals?

Fast forward about fifteen years, I am now entering my 4th year of vet school and plan to practice emergency medicine. Perhaps all these trips to the ER drove me down this career path, maybe I have just always loved the rush of emergency medicine. Although I am not practicing emergency medicine yet, I have gotten a taste of it through my time at the Wildlife Medical Clinic (WMC). Approximately once a week I am on call for any cases that may present to the clinic, and let me tell you, these are my favorite days! I love the rush of never knowing what will come through the door, the fast-paced environment, and getting to think on my feet. We see a wide variety of cases at WMC. In one shift, I may see an orphaned bunny, a hit by car owl, a squirrel presenting with neurological signs, and so much more. Today, I will take you along as we work through these three cases together!

First Part of ER Visit: Triage

Wildlife emergencies, like humans, all begin with triage. Triage is where we determine which case is the most urgent and who can wait a little longer. Once our patients receive their initial triage, we will begin working through each case, one at a time. So how do we work through and treat different cases? Let us go through it!

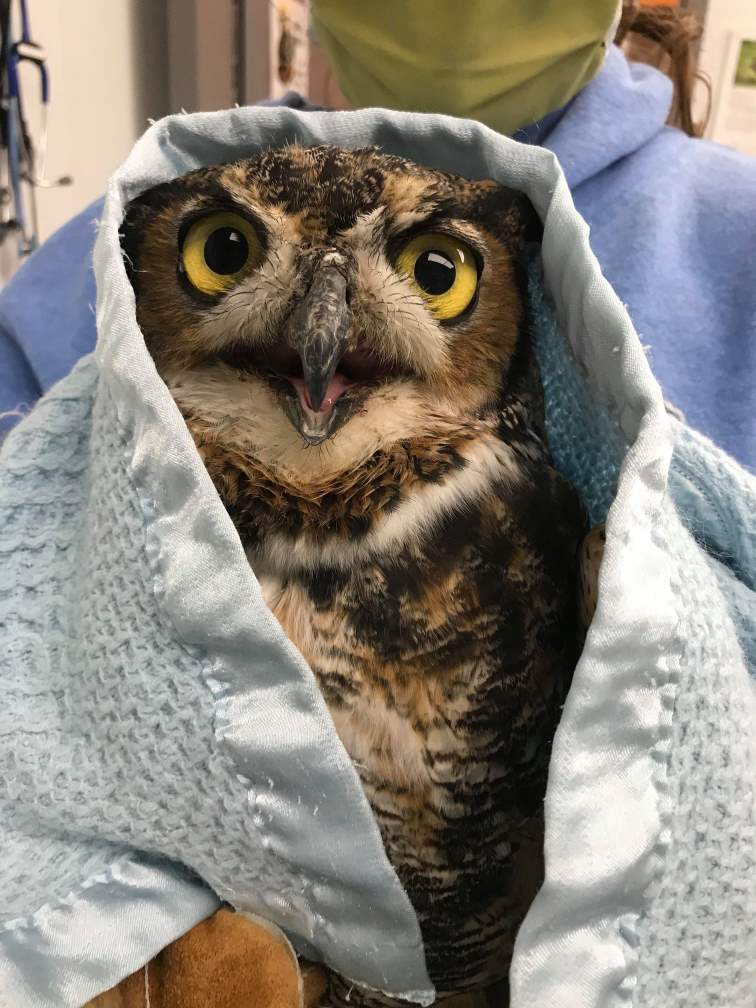

Great Horned Owl Case

We begin our shift with our hit by car owl. This Great Horned Owl or GHOW for short, presented with a brief history of being found unable to fly, on the side of the road. Our first step is to perform what is known as a hands off exam. Our wildlife patients are much different than domesticated cats and dogs. Typically, wildlife will hide their pain around humans out of fear or protection. Many can “mask” signs as we handle them. This is why observing them before we begin our physical exam is so important. During our hands off exam, we can appreciate a right-wing droop, as well as an obtunded mentation. In layman’s terms, our owl is dull and not very reactive. Our next step is to perform a thorough physical exam. During our physical exam, we are looking for any abnormalities present. Although it may be tempting to jump to the obvious injury first, it is important to assess every part of the patient to look for any more subtle injuries. Once we have completed our physical exam, the animal will briefly be returned to its enclosure to discuss our findings. We create what’s known as a differential diagnosis list of potential problems. For this patient, we have diagnosed a closed fracture of the right radius. Now, it’s time to discuss treatments. Our primary goal of triage is stabilization. One of the first treatments I will provide is analgesia, or pain medication. We have a variety of pain medications available at the Wildlife Medical Clinic. Typically for fracture patients, we provide an opioid, NSAID, and occasionally Gabapentin as well. All these medications act on different receptors and enzymes in the body, thus minimizing pain in a multitude of ways. Following this, we will apply a figure eight bandage to help stabilize the wing. This method is fairly similar to a human splint. The goal is to immobilize the joints above and below the fracture to allow the bone to heal. Our patient is looking better already! Our team agrees that this patient is stable. We plan to schedule radiographs, or X-Rays, at a later time to better assess the fracture.

Squirrel Case

Next on our triage list is our neurological squirrel. This Eastern Gray Squirrel, or SCCA, appears to be a juvenile male approximately 8 weeks old. During our hands off exam, we can see that this squirrel is ataxic, or uncoordinated. Additionally, he appears dull and unaware of his surroundings. During our physical exam, we recognize that he is dehydrated and has a body condition score of 1/5, meaning that he is very underweight. Besides the low body condition score, dehydration, ataxia, and dull mentation, we do not appreciate any other abnormalities. Due to this squirrel being 8 weeks old, ataxic, and with a low body condition score, hypoglycemia jumps to the top of our differential diagnosis list. Hypoglycemia, also known as low blood sugar, can cause incoordination in our young animals. Luckily, it is a very easy fix! We place a small amount of Karo syrup on the squirrel’s gums and he instantly perks up! Although he is looking better, we are not done yet. Our patient is dehydrated and obviously very hungry. We will begin by administering subcutaneous (just under the skin) or intravenous (into a vein) fluids. Since juvenile squirrels have very tiny veins, it is typically easier to administer these subcutaneously. Our patient will receive maintenance fluids, or what is needed in a day to maintain hydration, as well as deficit fluids, which is the estimated amount of fluids lost. Once these are administered, we can see that our squirrel is already looking better. We will provide this squirrel with food and keep him for observation until he appears to be back to normal.

Orphaned Bunny Case

Finally, we have reached our orphaned bunny. Our bunny was found at 1 p.m. The finder noted that he did not see the mom nearby and believed it to be orphaned. He did not notice any obvious injuries. During our hands off exam, we see that this bunny is very bright, alert, and responsive, or BAR. She is attempting to jump off the table and get away from the triage team. Although this may sound scary, it is a great sign in our wildlife patients. We love to see patients who are exhibiting normal wildlife behaviors, especially when they appear healthy. However, our bunny will still need a physical exam. We are quick and efficient with our physical exam to minimize stress to the animal. Luckily in this case, there are no abnormal findings! Our bunny appears hydrated, has an ideal body condition score of 3/5, and did not have any noticeable injuries. We place our patient back in her enclosure and begin discussing our case. Since we did not find any abnormalities, what do we do? Well, we begin by looking back at the history. Our bunny was found at 1 p.m. today. We know that mother rabbits typically return to the nest at dawn and dusk. During the day, the mother will avoid the nest to deter any predators from the nest. People will commonly believe that a rabbit is orphaned when its mother is not nearby; however, this is intentional to protect its young. Truthfully, I was unaware of this before working at the Wildlife Medical Clinic, so no need to be ashamed if you did not know. Since this bunny is healthy, we decide to call our manager and the doctor on call to receive permission to release this patient. Thankfully, permission is granted, and our patient can go back to the wild! We return the bunny back to the exact location she was found. Following this, we call the finder to provide an update and ask him to notify us if he does not see the mother later in the evening. Later that night, we receive a call that the mother has returned to her nest! Hooray! What a fantastic end to the day.

Debrief from a Busy Day

Wow! What a busy day for triage! By the time our bunny is returned to the wild, my team is off call and can return to “normal” vet school life. Our first-years gear up to study for their upcoming anatomy exam. The second-years go home to get ready for their next day of rotations. And us third-years finish up studying for our last exam ever before we head into clinical rotations in a few weeks. Well, this may sound like a lot on top of vet school, but I wouldn’t want to spend my weekend any other way. I hope you all enjoyed working through your first triage shift and if you ever wondered what happens at the Wildlife Medical Clinic ER, now you know!

This article was written by Raegan, one of Wildlife Medical Clinic’s third year student volunteers.