I have wanted to volunteer with the Wildlife Medical Clinic (WMC) since being accepted into the University of Illinois College of Veterinary Medicine. My goal is to become a zoo veterinarian, and volunteering in the WMC is the perfect opportunity to work with some of the species I might see throughout my career working with exotic animals, or at minimum I will see scenarios and cases that can be applied to others in which I will be involved in the future. I signed up right away with a lot of aspirations for what I could learn from the other students, faculty, and residents at the clinic. I started out semi-confident in my clinical skills as I had some small animal medical experience. I also have a zoology background with husbandry (daily care and needs) knowledge of the animals we might potentially see in the clinic. I was excited to finally combine the two experiences by volunteering in the WMC!

As I worked with the team and learned the ropes, I was able to work on two interesting cases before winter break that taught me a lot about the medical process of rehabilitation and what goes into a successful release. I was the secondary on those cases or the number two in who was making decisions, and I was very grateful that the primary on both cases was such a great mentor as I learned a lot from them.

During winter break I volunteered to come back to school early and help in the clinic for a little under two weeks before classes resumed. While I was working in the clinic, we had a crow that was in our care. I was made primary on the case, which meant I was the first person to be contacted if something was going on or someone had questions and I was the main person who would guide medical decisions. I was very excited for the opportunity and challenge but also terrified that I wasn’t ready. Luckily, the secondary on the case was a third-year veterinary student and team leader that I had previously worked with, so I was excited and relieved to have their expertise and experiences to help with this case.

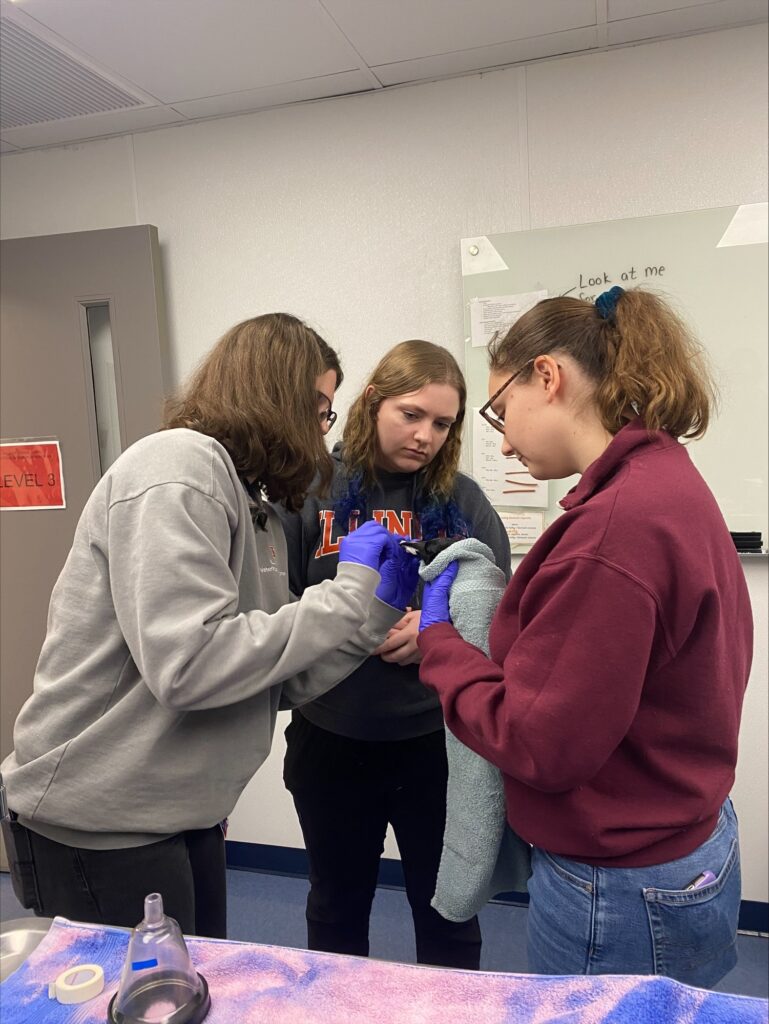

The crow came into the clinic in late December with a broken right humerus (a major bone in the wing). We were able to perform surgery to repair the break, which involved placing pins to hold the bone in correct alignment while it was healing. We put one inside the bone across the two fragments and then we had some on the outside of the wing to help stabilize everything. While the crow had his pins in his wing and the bone was healing, he couldn’t move it as well as he normally could. Therefore, we performed passive range of motion or physical therapy for the crow three times a week. This also allowed us to gauge his progress in healing. As the weeks went on, he was able to stretch his wing more and more, and eventually his bone was healed enough to remove the pins. We took new x-rays and confirmed that the bone had healed adequately, and we could start removing some of the pins.

First, we cut the connection between the pin inside his bone and the pins outside his bone. A few days later we were again performing his physical therapy but noticed that he had pulled out the pin that was inside his bone, all on his own. We once again took x-rays and confirmed that the bone was healed, and then proceeded with removing the rest of the pins. Crows are extremely smart and like shiny objects, so we think he noticed that the pin inside his bone was no longer attached to the external ones and was clever enough to pull it out on his own. Once all the pins were removed, we allowed our patient to continue to cage rest in a small space.

One week later, just before we hoped to transfer our patient to a wildlife rehabilitator for some time in a flight cage, we noticed bruises present over his right wing. Radiographs confirmed that he had rebroken his wing and in the exact same spot that had just healed! We are not sure exactly how he re-fractured the wing, but he was quite active in his enclosure, and may have hit it firmly against the walls of the cage. We again took this patient to surgery to place a slightly different type of external skeletal fixator. We moved him to a new enclosure in his own room and made sure everything was as soft and padded as possible and began the healing process again.

We increased the amount of enrichment provided to the crow by means of food puzzles and various toys to try to keep him busy and occupied so his wing could heal. As I mentioned before, crows are very intelligent animals and when we are caring for them it is part of our job to make sure they are using their brains and are mentally stimulated. We have some great puzzles that we hide their food in, various objects such as bells and mirrors that we had in this crow’s enclosure for the duration of his stay, and a variety of food to keep his diet interesting.

We fed this crow a mix of dry and soaked dog and cat food, wet dog food, rolled oats, cracked corn, berries, hard-boiled eggs, and variously sized mice. We also did our best to be as hands-off as possible and handle the patient only when absolutely necessary, which greatly helps to reduce stress while they are in our care. Following the second surgery, we began to restart physical therapy. On his first physical therapy session we found fresh bruising yet again. This once again led to further x-rays, which showed he had broken the same bone in a new location.

The new fracture was closer to his elbow than the original fracture. At this point, it was the crow’s second fracture of the bone in our care and the third fracture of that same bone within two months. After much discussion, we made the hard decision to humanely euthanize him based on the severity of the newest fracture and its proximity to the elbow. With all the injuries, we couldn’t guarantee that the crow would regain range of motion in that wing and been able to fly comfortably once released. We were also worried there might have been a nutritional or metabolic abnormality that led to repeat fractures.

We did the best that we could for the crow while in our care, and unfortunately, while it was not the outcome we hoped for, it was the right decision and the most humane option for this patient. Although this case did not have a positive outcome, I was still appreciative of the learning opportunities it provided. Upon reflection on this case, I recognize how much I have grown as a veterinary student. I was able to work very closely with the faculty, residents, and the managers throughout the process. I was able to build relationships with all these amazing people who are involved in the clinic by working on this complicated case with them. My team lead/secondary was there to help answer my millions of questions and really increased my confidence level. The faculty were a great support system for the harder questions we had while working with this crow and were there to help us every step of the way.

Without the mentorship of my team leader and the faculty in the clinic, I would not have learned as much as I did, and I’m extremely grateful to them for helping me. Working on this case allowed me to learn about avian orthopedics, the process of dynamic destabilization (taking the pins out in stages), case management, and treatment decisions which I will be using throughout other cases during the rest of my career. I enjoyed being that first point of contact to always be up to date and involved in the case. It was very intimidating to shift my thinking of myself from a student to a veterinarian. Making that shift mentally allowed me to think more about the medical decisions we were making, and I felt that I was very involved and integrated into the case.

When I think about my experiences in the Wildlife Medical Clinic so far this year, it all centers on increasing my clinical skills and confidence, and this case was instrumental in that. I am very lucky that I’m already hands-on with the entire medical process as a first-year veterinary student, and I can’t wait to see how much more I learn, grow, and gain from working with all the amazing other students, faculty, residents, and animals that we interact with at the wildlife medical clinic.

Written by Roxanne, Class of 2027