This account is by Katelyn Bagg, a rising third year veterinary student and one of the clinic’s full-time summer interns.

Working in a wildlife clinic on a daily basis is an adventure, as you never know what you will be presented with. We take everything from a litter of baby bunnies to an emergency hit-by-car raccoon, so we always have to be prepared. The summer is a busy season. It is always bustling in the clinic and there are constant opportunities to try new things and to learn.

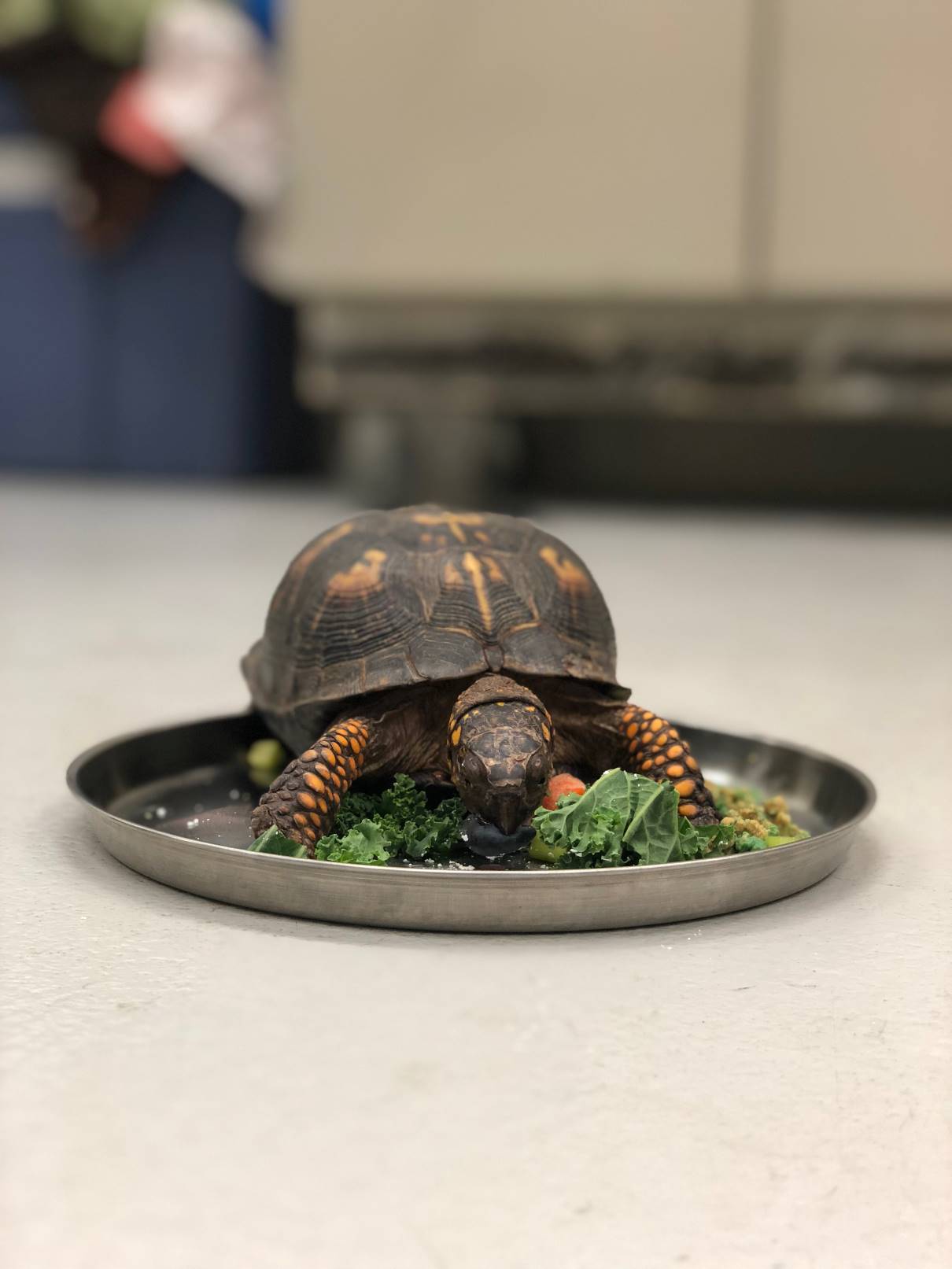

Katelyn ensuring a new patient with neurologic and motor symptoms is able to chew and swallow its food normally.

Interns are in the clinic almost every day, giving us the opportunity to follow cases from intake to the resolution of symptoms. It is one of the most rewarding feelings to get to release a patient you have worked with, which is exactly what I got to do for a juvenile red tailed hawk that came in this June.

The young hawk presented on June 5th with no obvious musculoskeletal abnormalities, but was very thin and dehydrated. Blood was drawn for diagnostic purposes, and showed that the patient had an active inflammatory process. He was offered food, but was not eating on his own. Due to the fact that he was so thin, we decided to tube feed him a liquid carnivore diet to make sure he could get the nutritional support that he needed. When volunteers tried to pass a feeding tube down his esophagus, they noticed that there was a mass in the back of the throat that made the tube difficult to pass and probably prevented the hawk from being able to swallow on his own.

There are a few things that can cause masses and plaques in the oral cavities of birds, and with a swab of the area, we were able to narrow it down. Our hawk had trichomoniasis, an infection caused by a small protozoan parasite. We started him on Metronidazole to help kill the parasites. The mass dislodged and was removed several days later, but our patient was still not eating on his own. On June 21st, he was anesthetized for an endoscopy, which allowed us to get a good look at what was going on in his esophagus. There were open sores that were infected with different bacterial species, so the area was then treated like a wound. We gave him an anti-inflammatory medication, an antibiotic, a pain medication, and a medication to protect the ulcerated tissue from further damage.

Our hawk gained weight and started to become more lively. He would vocalize when bored or hungry, so volunteers had to come up with creative ways to keep him entertained. His mice were hidden in various items like kongs or hand made newspaper hides so that he would have to forage for food as a form of environmental enrichment.

The juvenile hawk interacting with a clinic volunteer; beneath its perch, the cardboard box filled with shredded newspaper was an enrichment “hide box” for food items.

Finally, on July 10th, our patient was ready to go back into the wild. He was eating on his own and gaining weight, and his throat looked great with no new evidence of infection and no return of his plaques. It was a warm, sunny evening, and with a little coaxing, our hawk flew away across a field and landed in a nearby clearing.

The inquisitive young hawk took its time adjusting prior to flying away.

The inquisitive young hawk took its time adjusting prior to flying away.